“My daddy, he made whiskey

“My daddy, he made whiskey

And my granddaddy did too

And we ain’t paid no whiskey tax

Since Seventeen Ninety-Two.”

—Albert Frank Beddoe

The notorious gunfighter John Wesley Hardin was given a 25-year prison sentence for murder in the second degree after

being convicted in the district court of Comanche County, Texas, for killing Brown County Deputy Sheriff Charlie Webb.

Nearly 25 years after the deadly shoot-out, in 1897, almost 500 miles to the northeast, in the mountains of Arkansas, William Harvey “Harve” Bruce would kill two deputy U.S. marshals and put hot lead into two posse members, while the other two scattered like quail into the wild and uncut Boston Mountains. Fate gave him a better hand than Hardin got.

A Dead Shot

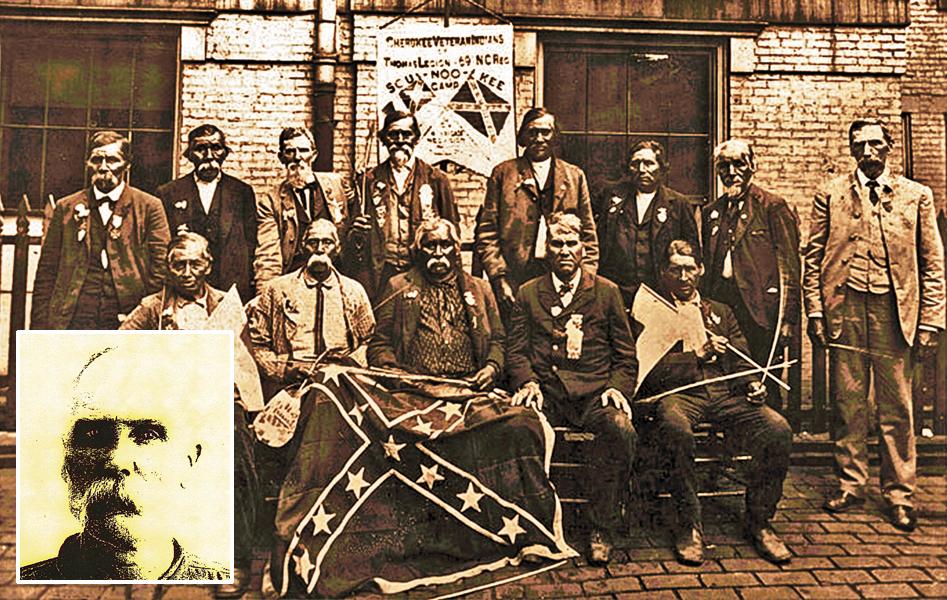

Bruce grew up experienced in the use of firearms. He was just 16 years old when he joined the confederacy in William Holland Thomas’s North Carolina legion of Cherokee Indians and mountaineers. Young Bruce proved himself in a number of battles and gained the reputation as a dead shot before reaching his 17th birthday.

On Sunday morning, August 29, 1897, 55-year-old Bruce was visiting, or so he claimed, friends who were operating a still in Bullfrog Valley, Pope County, Arkansas. “Everyone knows where the Bull Frog Valley is…. That is where the genuine wild-catter [moonshiner] blooms and flourishes as prolific as morning glories on the back porch of a farm house,” reported The Mountain Wave newspaper in Searcy County.

Almost two months prior, on June 28, the Bullfrog Valley Gang, “one of the most dangerous organizations of counterfeiters that has operated in the United States in recent years,” was reported “wiped out.” Deputy U.S. marshals had captured the leaders of the gang, headquartered in Pope County, who had floated money to “nearly all the principal cities in the country” and even in Toronto in Canada. Bullfrog Valley was indeed a hotbed of criminal activity.

Bruce was sitting on a fence, talking to his friend, when he spotted a number of men mounted on horses headed his way. Bruce claimed the men opened fire without warning when they approached the camp. He grabbed his rifle and returned fire.

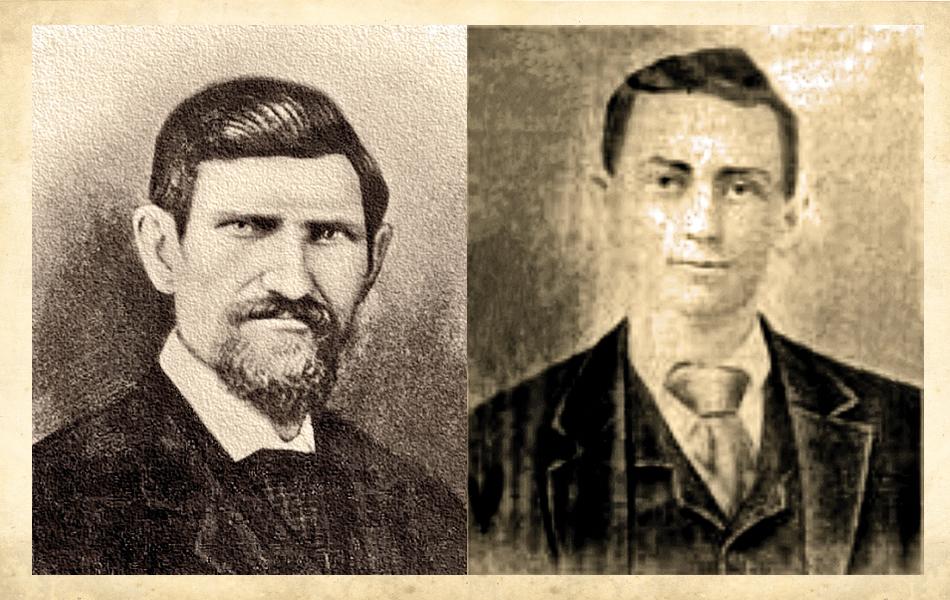

His first shot killed Capt. Benjamin F. Taylor, and his second shot killed Joseph Dodson, both deputy U.S. marshals. Taylor, of Searcy County, was a wealthy 57-year-old farmer who had served time as a senator in Arkansas before embarking on his career as a deputy in 1895. The 28-year-old Dodson, of Stone County, had a reputation for busting moonshine operations throughout the region.

Still under attack, Bruce spotted another man, whose elbow was exposed from behind a tree. One shot put him out of action as he howled and fell to the ground. Bruce’s next shot seriously wounded one man crawling on his belly by putting the round into his hip.

Three men allegedly running the moonshine still were captured a few weeks later. They were Turner Skidmore, James Alva Church and Dave Millsaps. All were charged with murder and illicit distilling.

Must Not Be Paroled

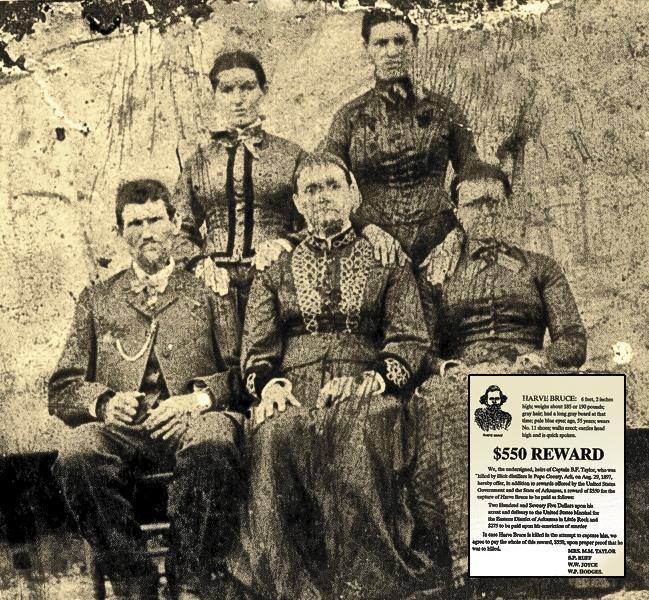

Bruce evaded capture for a year. The Taylor family posted a reward, offering $550 for Bruce’s capture, dead or alive. Other rewards increased the amount to $1,000.

Bruce finally let his guard down and went home to his family. J.W. Gist, a friend, neighbor and cattle trader, was watching the house and saw Bruce enter. That night, when Bruce sat at the table, with his rifle propped against the wall, Gist crashed in through the door and grabbed Bruce’s rifle. Gist and his son handed off Bruce to authorities. That is the story printed in the newspaper, but family lore claims Bruce convinced the Gists that he would let them turn him over to the law, with the understanding that the reward would be given to him. “I’ll need a good lawyer, and that money will fill the bill,” he told them.

When the case reached district court in Pope County, the federal government threw a monkey wrench into the grinding gears of justice. The U.S. attorney put the brakes on the murder trial, saying, “These men will first be tried for Illicit Distilling and will take precedence over the murder trial. You can have them only after they do their time in federal prison.”

Bruce, Skidmore and Church were convicted for illicit distilling and sentenced to three years at Leavenworth in Kansas. Millsaps was acquitted. Bruce arrived at the prison on November 6, 1898. He gave his occupation as farmer; of course, a moonshiner must have grain to make his Devil’s brew. His prison record was flagged with the statement, “Must not be Paroled. Notify sheriff in Little Rock, Ark., 2 mo’s prior to discharge; by order of warden.”

On July 19, 1899, Bruce, Church and Skidmore were released to the custody of the state of Arkansas to stand trial for the murder of those two deputy marshals.

“My Life Was in Danger”

Bruce probably never heard of Hardin and his sentence of 25 years for killing a county lawman. But he had heard of “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker. Although the judge had died in 1896, Bruce knew, without a doubt, that anyone killing a lawman was surely going to swing by the neck.

In Fort Smith, the men were tried for Taylor and Dodson’s murders. At the trial, Bruce said, “I did all the shooting under the mistaken idea that my life was in danger.” He testified that the posse members did not identify themselves as lawmen nor did they state their intentions. Bruce believed he was being attacked by a rival gang of moonshiners. He was the only one shooting back, he said, adding that his friend had fled the scene when the posse shot at them.

The jury acquitted everyone except Bruce. He pleaded self-defense. The prosecution’s case looked weak; strangely, the wounded posse members who survived the attack, Clay Renfro and S.B. Lawrence, were not called on to testify. With many citizens resenting the government’s stand against making moonshine, a jury of his peers convicted Bruce of involuntary manslaughter. He was sentenced, not to hang, not 25 years busting big rocks into little rocks, but a meager six months.

The Taylor family had to be fuming. They had paid $550 hard cash for his capture, and he was given six months in prison for the murders of two cops—a lighter sentence than Bruce had gotten for illegal distribution of moonshine. The court records are not clear, but perhaps Judge John Henry Rogers considered the stint at Leavenworth as time served. The charge may have been downgraded from murder to justifiable homicide for the dead cops and assault for the wounded cops. If the marshals charged in without identifying themselves, as they often did, the jurors probably saw Bruce’s actions as reasonable.

Escaping the Noose

During Judge Parker’s rule, the Western District of Arkansas dealt with nearly 4,000 liquor violators between 1875 and 1896. For first convictions, Parker often gave out six-month sentences per offense. During that same time period, grand juries issued 3,942 indictments for murder, but only 161 killers were convicted.

Upholding federal laws in the Fort Smith, Arkansas, courthouse, which oversaw the 74,000-square-mile Indian Territory, was a massive responsibility. Parker earned a reputation for hanging the most dangerous of these offenders. But under Judge Rogers, Bruce did not pay for his crimes with his life.

To add insult to injury for the Taylor family, the court turned Bruce loose on his own recognizance, so he could arrange his business affairs, and then report to the penitentiary in Little Rock. He did.

By the following summer, Bruce had landed himself in a unique position. In August 1900, while discussing the building of a new prison, Superintendent Bud McConnell told his supper guests, J.E. Little, Dr. Foster Richardson and J.W. Underhill, about his inmate Bruce. “He is now a guard on one of the walls,” McConnell said. “I told him being he could use a Winchester so dexterously on marshals he would make a good guard. He impresses me as one that would keep his promises, if possible.”

Not only did fate give this cop killer a far lighter sentence than Hardin had gotten, but Bruce incredibly ended his incarceration with a job as a prison guard.

Old Habits Die Hard

After Bruce returned home to Van Buren County, the mountaineer still hated federal and local lawmen because both tried to prevent him from doing with his corn as he pleased. He felt he had as much right to make whiskey with his corn as his wife had to use it to make bread. He once argued, “Now, corn is selling for .30 cents a bushel, which is no kind of profit for the purse. But I can take that bushel of corn, make corn whiskey and sell it for two dollars a jug, then take the used corn and feed it to my hogs and they get just as fat and happy. It was money well needed for a poor mountain man.”

He returned to illicit distilling, and he was nabbed a second time. Luckily, he didn’t shoot, kill or wound anyone. Back to Leavenworth he went, on May 16, 1901, for another three-year sentence and a $500 fine. He ate an early Thanksgiving meal in prison and was paroled the next day, on November 26, 1902.

The mountaineer moonshiner and killer of men was well known as the best rifle shot in Arkansas. News articles often told of his hunting skills, reporting, “For Harve: Three Deer, Three Shots” or “Bruce kills three deer out of five while chasing them on the back of a mule.”

After Bruce was released from Leavenworth the second time, he again became a prison guard. His son convinced him to stop making moonshine and to accept the meager .30 cents a bushel for his corn.

Norman W. Brown is coauthor, along with Chuck Parsons, of A Lawless Breed: John Wesley Hardin, Texas Reconstruction, and Violence in the Wild West. Brown also cowrote Early Settlers of the Panhandle Plains.

Photo Gallery

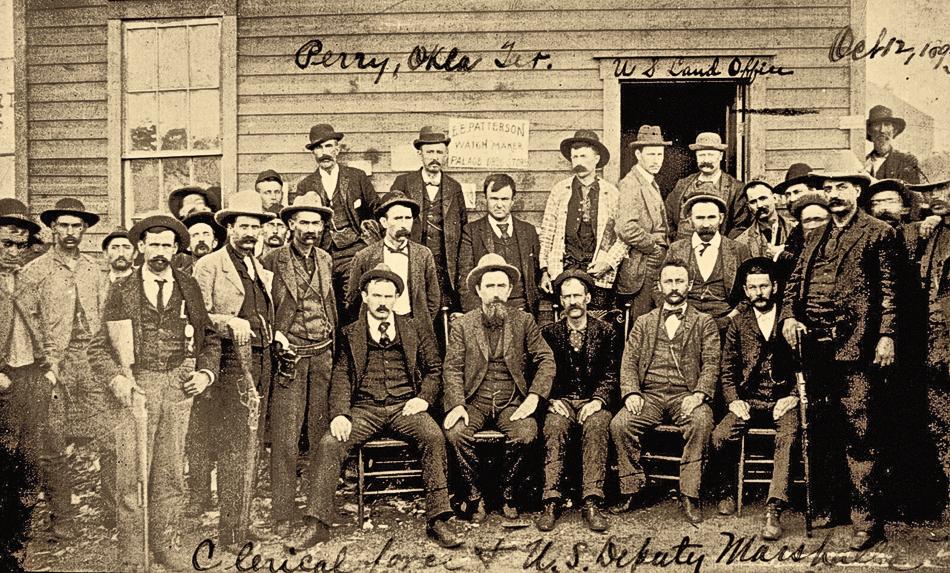

– Courtesy Susan Swain Peters collection, Oklahoma Historical Society –

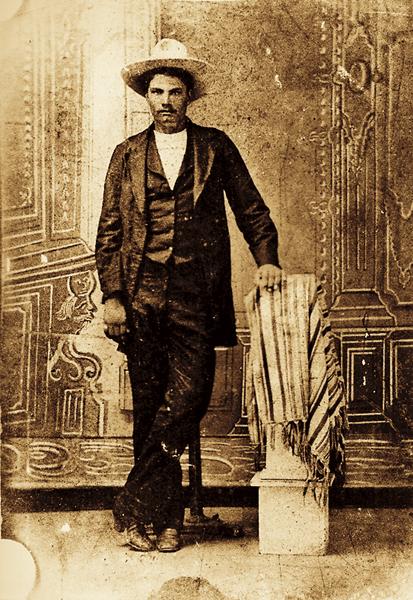

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Dodson courtesy Norman W. Brown;Taylor courtesy Tinkalew Collection –

– Taylor family Courtesy Tinkalew Collection; Wanted poster courtesy J.D. Fortner –

– Courtesy J.D. Fortner –