Legendary rock musician Phil Collins doesn’t exactly believe in psychics, but he has to admit, he feels eerie about this: A clairvoyant once told him he was the reincarnation of John W. Smith—an Alamo courier who went on to become the first mayor of San Antonio.

Legendary rock musician Phil Collins doesn’t exactly believe in psychics, but he has to admit, he feels eerie about this: A clairvoyant once told him he was the reincarnation of John W. Smith—an Alamo courier who went on to become the first mayor of San Antonio.

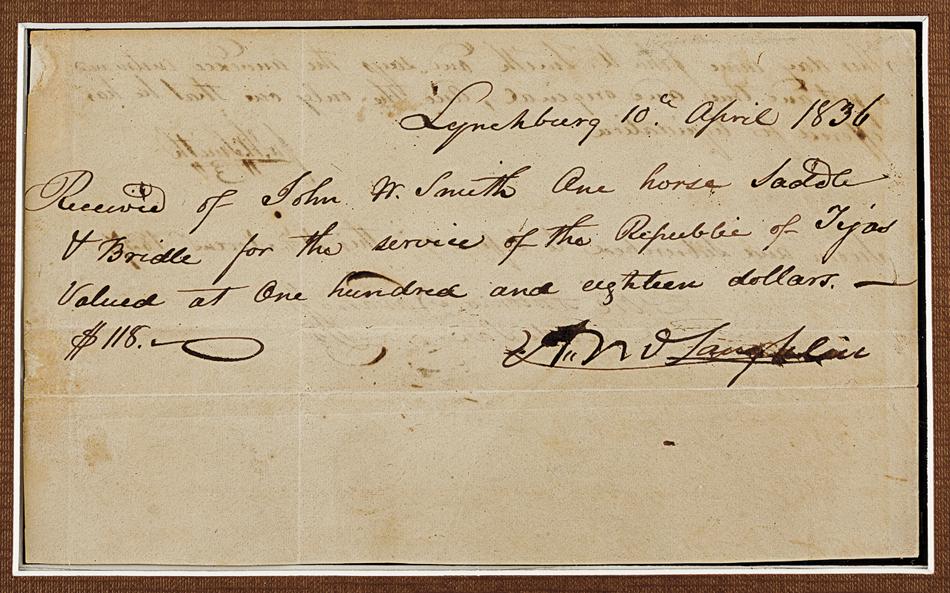

She didn’t know that the very first item in his vast Alamo collection was an 1836 receipt for Smith’s new saddle just weeks after the Alamo siege.

“My third wife bought it for me and had it framed for a present in 1994,” Collins says. “And then there I was, at a party in San Antonio years later, and a clairvoyant claimed that I was Smith in a former life. There’s no pictures of him. I don’t want to go weird. I’m just fascinated by it.”

That isn’t the only thing that spooks this retired British musician who has just donated more than 200 Alamo items—worth some $15 million—to the Alamo in downtown San Antonio, Texas.

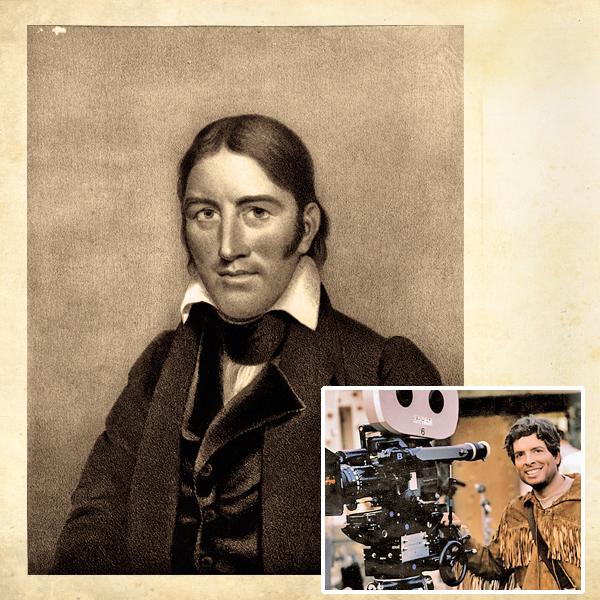

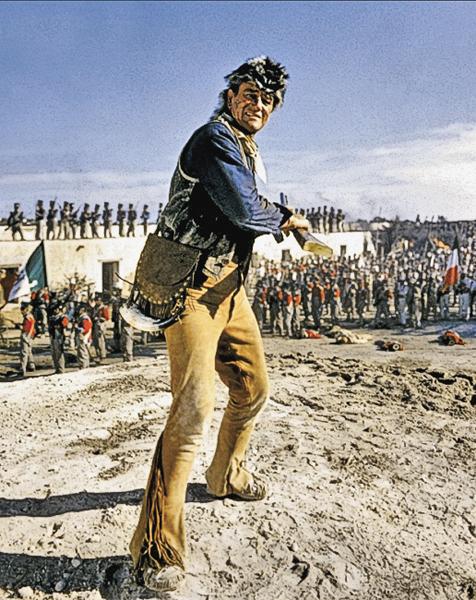

The fascination with the pivotal battle in the Texas Revolution began in the 1950s, when Collins was growing up in London and watched the 1954-55 Disney miniseries on Davy Crockett, played by Fess Parker.

“I used to go out in the garden and play the Alamo,” he says. “I couldn’t get any music to go with the battle, so I played the ‘William Tell Overture.’ I’d enact the battle with my rubber and plastic soldiers, and afterwards, I’d burn the soldiers in a bonfire. I didn’t know it then, but that’s what happened in real life—the bodies were burned on funeral pyres.”

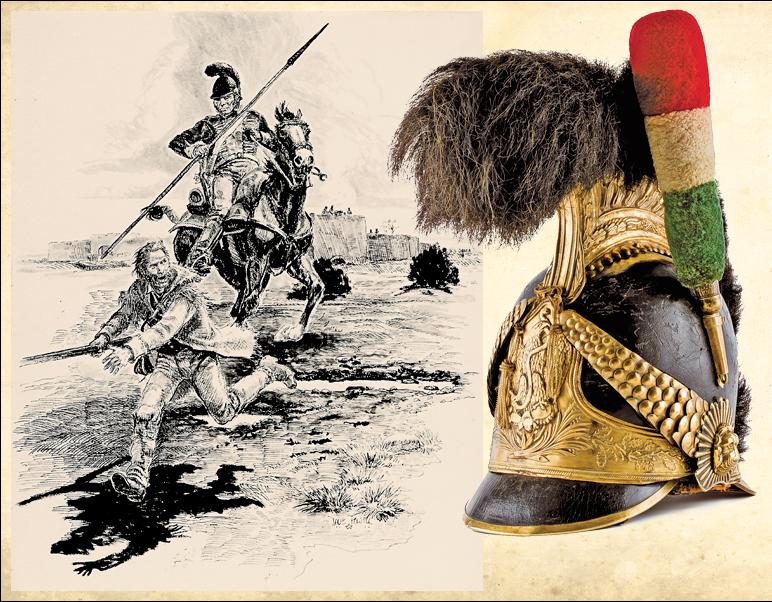

Collins started reading whatever he could find about the 13-day siege in 1836 that killed roughly 250 Texian defenders (almost to a man) who fought approximately 2,300 Mexican soldiers under the command of Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna.

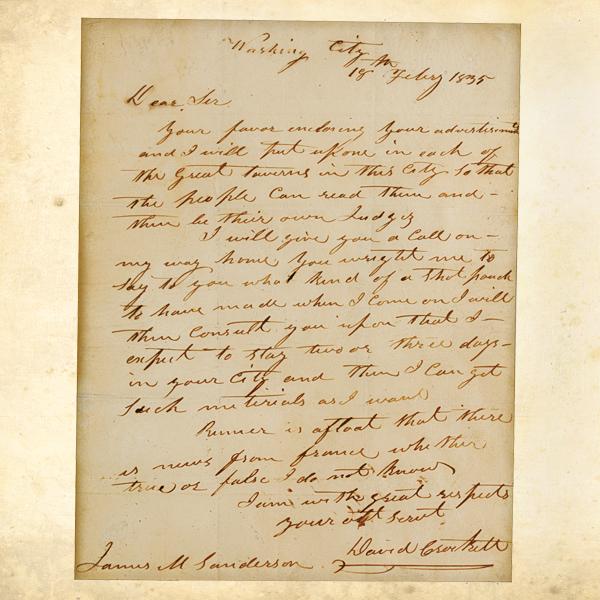

He was getting rich about the time he saw his first memorabilia item tied to the battle and its participants—a David Crockett letter in a Georgetown shop he spied while shopping with his first wife in Washington D.C. “But they wanted $60,000 for it, and it was too expensive,” he says, noting his mother taught him to be more frugal than that.

Several years later, his third wife gave him the Smith receipt that would begin the world’s largest private collection of Alamo artifacts. The collection grew so large that he created a state-of-the-art museum inside his home in Switzerland.

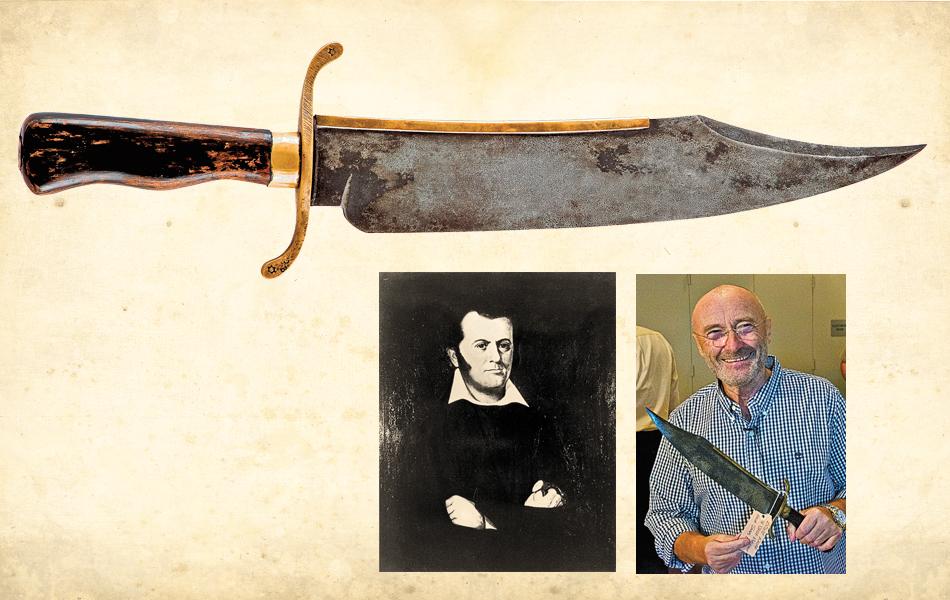

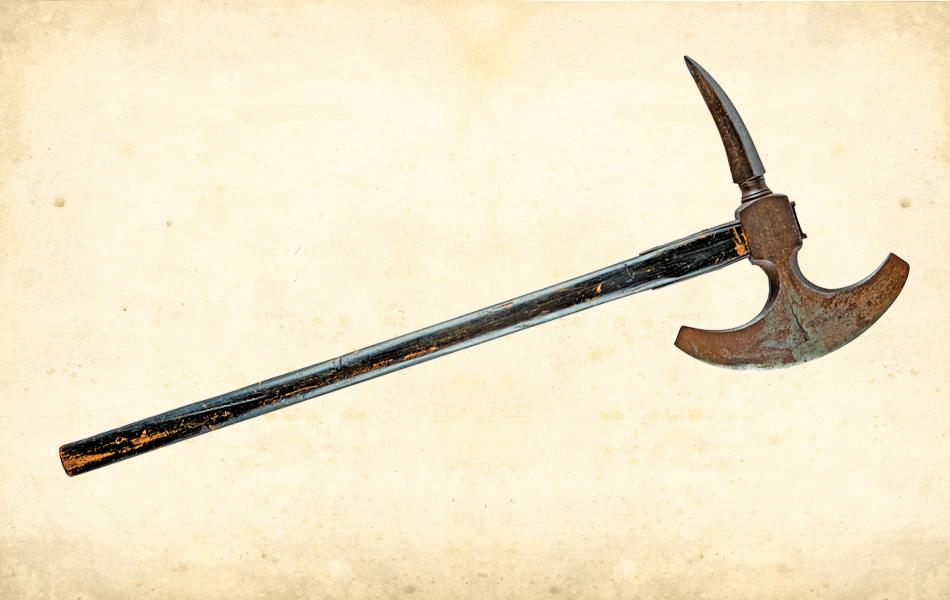

That Smith receipt is still one of his favorite items. But he lists the “jewel in the crown” as the David Crockett musket, with two powder flasks, musket balls and a musket pouch he bought from the José Enrique de la Peña family of Mexico. Their ancestor was a lieutenant colonel in the Mexican army whose diary, published in 1955, created an outrage when he wrote that some had surrendered in the end, including Crockett. American historians—and movies and books—insist Crockett was killed fighting to the end. But the dueling stories make the musket a controversial item and a special piece of Collins’ collection.

“I’ve bought a lot of my collection from Mexico,” he says, sharing how Mexican soldiers who survived the Battle of the Alamo took home the “spoils of war,” from boots to weapons.

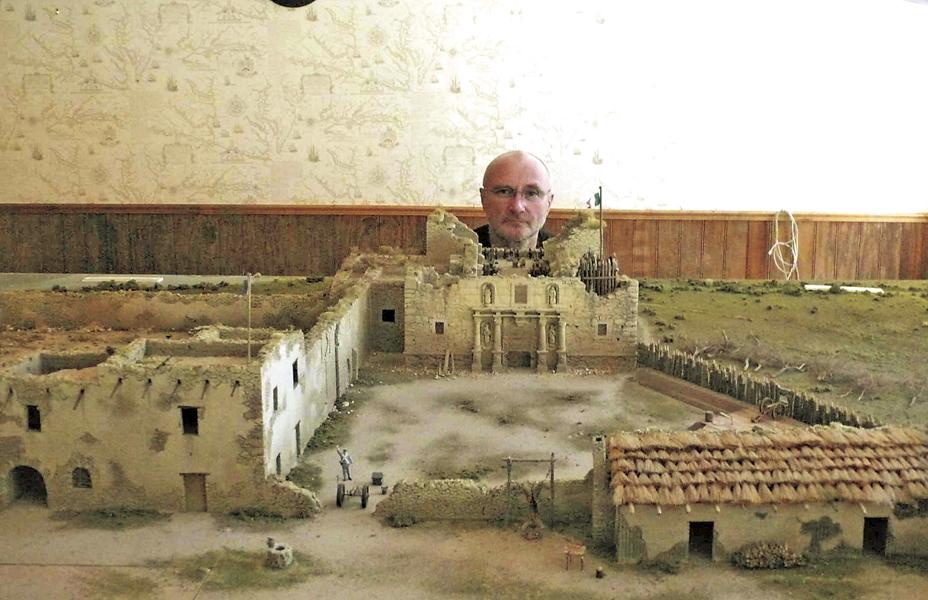

Collins also helped dig for Alamo artifacts beneath the History Shop at 713 E. Houston Street, opposite the north wall of the Alamo compound. Jim Guimarin, who owns the antique map, weapon and book shop, showcases Mark Lemon’s model of the Alamo created for his book, The Illustrated Alamo 1836. When the author had to sell it because he needed the garage back, Collins bought it so it could be temporarily stored at the History Shop. The hope is that the model will make its way to the Alamo too.

“The real story of the Alamo is less black and white than the movies present it,” he says. He points out that this land was part of Mexico at the time, and Santa Anna had invited settlers to till the land. The first settlers did, following Mexican law, but then word got out that Mexico was giving away land and that created a surge that led to the demand for independence.

Collins admits his family was conflicted over his generous donation. “My three oldest children are very pleased that the collection is going where it is supposed to go,” he says, “but my two little ones, especially the nine year old, were a bit upset I was giving it away. He knows all the characters. I’m keeping some Alamo movie things for him, and a big stone from the Alamo.”

While one would think the collection should obviously end up at the Alamo, Collins reveals that it was actually a fluke.

Collins went to San Antonio to visit various museums to see if they wanted his collection. “I’d walk in and say, ‘I’m Phil Collins, and I have this Alamo collection.’ My only stipulation was that most of it would get displayed,” he says. “But that night, I went out to dinner with a friend and a lady I didn’t know. She was Kaye Tucker, who works in the Texas General Land Office. She asked me if I’d let the Alamo have it. I’d never have asked, because I knew they didn’t have the space. But she said they’d build a new building. Right then and there, I said, ‘Yes.’”

Tucker well remembers that night. Her version includes a lot more butterflies in the belly. She recalls being thrilled that she was sitting across from the famous Collins and thinking to herself then, “This is nuts!!”

“I’m sure Phil was wondering what the heck I was doing there to begin with, but just assumed his friend and History Shop partner Jim Guimarin was just being nice and invited me. Phil was very relaxed and enjoying his favorite, cheese enchiladas, when Jim asks, ‘Kaye, do you have something you want to ask Phil?’ I was just inhaling a big spoon of soup, and it almost ended up everywhere!

“Phil asked, ‘Really, what’s that?’ So I asked, ‘Would you consider giving your collection to the Alamo?’ He looked at me, cocked his head slightly to the right and, even though it was only about a three-to-five-second pause, about 1,000 thoughts passed through my head, from ‘Are you nuts?’ to ‘Now, who are you again?’ to ‘You must be joking’ to ‘You need to catch a cab back to your office’ to ‘Let me think about it’ to (the desired response) ‘Yes, I would love that!’”

He, of course, said yes. Later on, Texas officials told Collins he could be as involved as much as he would like, from delivering the collection to being completely involved. “Completely involve me,” he told them, and their agreement notes he will be consulted on how his collection is displayed.

So what does someone obsessed with the Alamo do after he’s donated a vast collection to the Alamo?

“I’m still going to collect,” Collins admits. “I still find it enjoyable. It’s my obsession. I’ve gotten to know other collectors, and we all have a pleasure in passing things on for other people to enjoy.”

He’s known all these years that he’s not just collecting “treasured heirlooms,” but is collecting “real history,” he says. That history speaks directly to brave men fighting for what they thought was right…and left an imprint on an entire nation.

Jana Bommersbach interviewed Phil Collins for this article. His book, The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey, is available as a signed, limited edition from State House Press. Please visit TFHCC.com to purchase.

Photo Gallery

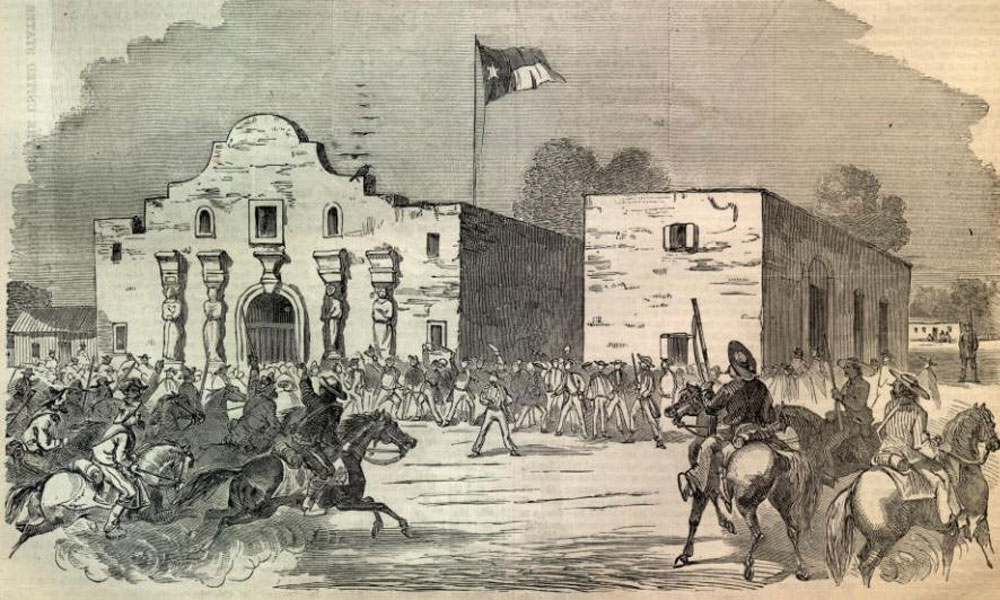

– Courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin –

– True West Archives –

– Collins photo Courtesy Texas General Land Office; Musket photo Courtesy State House Press, TFHCC.com –

– Courtesy State House Press, TFHCC.com –

– Courtesy David Zucker –

– Courtesy State House Press, TFHCC.com –

– Collins photo courtesy Texas General Land Office; Bowie print Courtesy Joe Musso; Bowie knife photo courtesy State House Press, TFHCC.com –

– Courtesy Texas General Land Office –

– Courtesy United Artists –

– Illustrated By Dave Powell –

– Courtesy Texas General Land Office –

– Courtesy Phil Collins –

– Courtesy Texas General Land Office –

– Courtesy State House Press, TFHCC.com –