This is surreal-and, no, I’m not stoned on peyote.

I’m at a Cache, Oklahoma, trading post, a 1970s-era cinderblock building full of … well, not quite the selection of Indian crafts you’d find at a Navajo reservation trading post.

A rusty sign points the way to what used to be Eagle Park, and I’m waiting for my guide to take me back through the locked gates and falling-down amusement-park rides to the Star House. A few locals sit outside, smoking cigarettes and giving me the “What-the-hell-is-he-doing-here?” look. “Isn’t it obvious?” I want to tell them, “I’m a huge fan of Quanah Parker!”

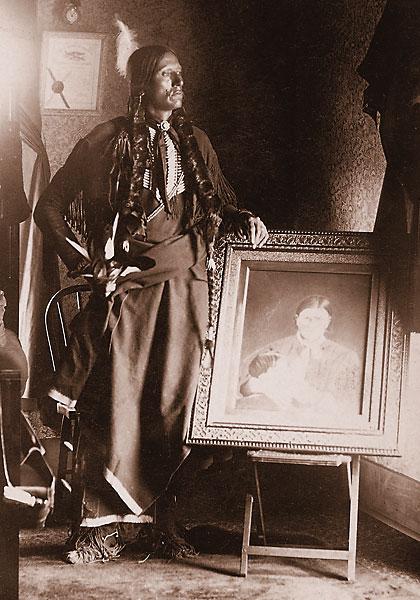

Everybody should be, yet it’s becoming obvious to me that a century after his death, the last chief of the Comanche Nation—the half-breed warrior who embarrassed Col. Ranald Mackenzie at Blanco Canyon in 1871, who led the Kwahadi band at Adobe Walls in 1874 and who, after surrendering in 1875, helped his people adapt to reservation life—is fading from public memory. This great American who would befriend Texas ranchers, help save the buffalo and have President Teddy Roosevelt as a house guest is mostly forgotten.

Eventually, Donna (she won’t tell me her last name) arrives, and we begin an impressive Quanah Parker tour. Yes, the Star House is open for guided tours via the trading post (call 580-429-3420 to make reservations).

The U.S. government, Donna tells me, built Quanah a two-bedroom home in 1878, but by the 1880s, Quanah needed something larger—he had six or seven wives—so Texas cattlemen led by Burk Burnett began building the two-story Star House, named for its roof patterns.

Moved from the Wichita Mountains to its present location in the 1950s—back when Eagle Park was becoming a big Oklahoma tourist destination—the Star House has fallen on tough times. It’s still standing, with firm floors, but in desperate need of restoration. In the late 1990s, burglars made off with many historic artifacts, including the photograph of Quanah’s mother and his sister that Quanah hung next to his bed.

In this home, he entertained not only President Teddy Roosevelt, but also rancher Charles Goodnight (who slept on the porch), Generals Nelson Miles and Hugh Scott, British Ambassador Lord Brice and Sioux Chief American Horse, yet I’m walking through dead leaves because of a hole in the roof!

Quanah deserves better.

Texas Traditions

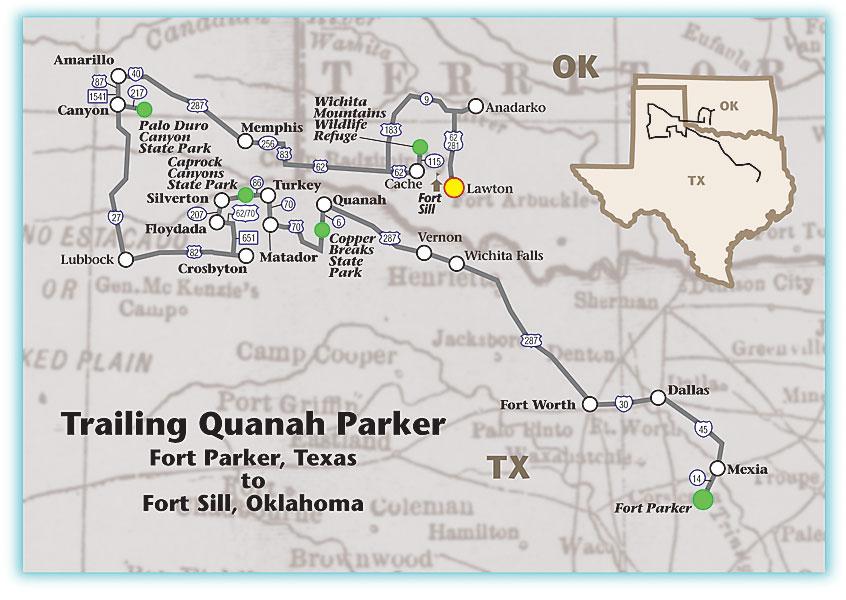

The story—and road trip—of Quanah Parker really begins more than 280 miles southeast in Limestone County, Texas. On May 19, 1836, Comanches raided the settlement of Fort Parker, established in 1833, and made off with several captives, including a young girl named Cynthia Ann Parker. Comanche chief Peta Nocona would take Cynthia for a wife, and around 1850, Cynthia would give birth to a son. He was named Quanah. Biographer S.C. Gwynne makes a persuasive argument that Peta was killed (although Quanah always denied this) when Texas Rangers smashed the Comanche encampment on the Pease River in 1860 near present-day Crowell, Texas. Quanah’s mother and his sister Prairie Flower were captured. Prairie Flower would die within three years, and Cynthia, who never readjusted to living with whites again, died, unhappy, in 1870.

In 1936, the Civilian Conservation Corps reconstructed Fort Parker as a centennial project back when Fort Parker was a state park. These days, the site is managed by Limestone County and the cities of Mexia and Groesbeck, but the replica stockade still stands, and the fort is host to several annual activities, including an 1800s Scottish Highlanders camp (first week of February) and a spring rendezvous (April).

For some reason, Texas seems to care more about Quanah than Oklahoma does. Maybe it’s because he was, after all, a native son.

Quanah took part in the State Fair of Texas in Dallas in 1910, arriving in an automobile with his family. No word on what he thought of the corn dogs or the Midway carnival zone, but The Dallas Morning News described him as a “…striking figure. He was attired in ordinary street costume and a soft black hat, his braided locks, tied in two plaits down his back, his erect bearing, his seamed and wrinkled countenance immediately disclosed to most observers his identity.”

At the Fort Worth Stockyards, I find a life-size bronze statue of Quanah and a historical marker. Quanah rode in the “grand entry” of the National Feeders and Breeders Show in 1907. He almost died in Cowtown too. In 1885, while staying at a Fort Worth hotel—not the Hyatt Regency, where the Quanah statue can be found—his roommate Yellow Bear blew out the light, unaware that the lamp was gas, not kerosene. Yellow Bear was asphyxiated, and Quanah remained unconscious for two days.

By that point in time, Quanah was becoming nationally known. In 1884, a town was named after him in Hardeman County, and in 1890, Quanah came down to bless Quanah, Texas.

“It is well, you have done a good thing in honor of a man who has tried to do right both to the people of his tribe and to his pale faced friends,” Quanah said. “May the God of the white man bless the town of Quanah. May the sun shine and the rain fall upon the fields and the granaries be filled. May the lightning and the tempest shun the homes of her people, and may they increase and dwell forever. God bless Quanah. I have spoken.”

Warrior Days

Before he became a celebrity, Quanah was feared.

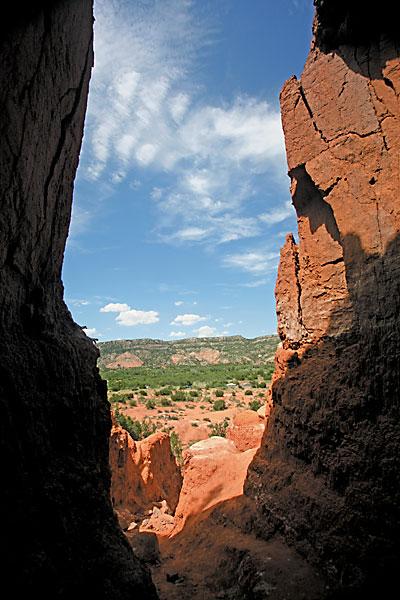

The Texas Panhandle was the realm of the Kwahadi band of Comanches. This was rough country, and you can get a taste for it near Quanah, Texas, by driving past the Medicine Mounds (which the Comanches revered) or spending time at Copper Breaks and Caprock Canyons state parks. Comanches used to trade with Comancheros near the unheralded but truly spectacular Caprock Canyons.

About eight miles southeast of Crosbyton is Blanco Canyon. There, in October 1871, Quanah led a raid on Col. Mackenzie’s supply camp and made off with more than 60 horses. Army Capt. Robert G. Carter got his first glimpse of Quanah: “A large and powerfully built chief led the bunch, on a coal black racing pony. Leaning forward upon his mane, his heels nervously working the animal’s side, with six-shooter poised in the air, he seemed the incarnation of savage, brutal joy. His face was smeared with black warpaint, which gave his features a satanic look.”

A young private named Seander Gregg also got a close look at Quanah, but he didn’t live to write about it. Quanah blew Gregg’s brains out.

Another excellent glimpse into Quanah is found at Canyon’s Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, one of Western history lovers’ greatest treasures. In 1960, Quanah’s widow Topay donated Quanah’s eagle-feather headdress and staff to the museum, which are both sometimes on display at the museum, while Quanah’s Winchester Model 1873 repeating rifle is on permanent display. Count on spending a really long time at the museum, which offers other wonderful glimpses into the Panhandle’s past.

The beginning of the end of Quanah’s warrior days occurred at Palo Duro Canyon, America’s second-largest canyon and, at 120 miles long, 20 miles wide and with a maximum depth of 800 feet, almost as impressive as Arizona’s famous hole in the ground. In September 1874, Mackenzie got revenge on the Comanches when he led the 4th Cavalry in a surprise attack. Casualties were light, but the Comanches and their Kiowa allies lost food supplies and some 1,400 horses—most of which Mackenzie ordered destroyed.

This is still Comanche country. Well, sort of. In Amarillo, I drop in at the Kwahadi Museum of the American Indian, home to a Boy Scouts of America Venture Crew with a history of Indian dances dating to 1944. Of course, most of the art and artifacts on display aren’t Comanche, and most (if not all) of these boys are whiter than I am. When I ask a 10 year old what he knows about Kwahadis, he tells me, “They were mostly dancers.”

Sigh.

Still, you’ve got to give these Scouts credit for at least remembering the Comanches. And their dances are quite popular. Or so I’m told. I’ve never seen them dance. With more than 3,800 performances in 48 states and overseas, these Kwahadis seem to cover more ground than their namesake warriors did in the 1800s.

In June 1875, Quanah surrendered his band to Mackenzie near Fort Sill. That brings me to Oklahoma, on U.S. Highway 62, better known as the Quanah Parker Trailway. It leads me to not only the Star House in Cache, but also to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, which Quanah helped persuade President Teddy Roosevelt to establish in 1901. In 1907, Donna tells me during my Star House tour, 15 buffalo were reintroduced into the Wichita Mountains. Today, the herd is maintained at roughly 650.

Quanah would be happy. I bet he’d especially enjoy the longhorn-beef hamburgers at the Meers Store, nestled in the heart of the Wichitas.

On to Oklahoma

I head north to Anadarko to view the Indian Hall of Fame and Southern Plains Indian Museum before hitting Lawton to tour the small but fascinating Comanche National Museum and the sprawling and historic Fort Sill.

Geronimo’s grave might be the fort’s biggest tourism draw, but I’m headed to the post cemetery’s Chief’s Knoll.

On December 4, 1910, Quanah had the remains of his mother and sister re-interred at Post Oak Cemetery near Cache. Less than three months later, on February 23, 1911, Quanah died in the Star House.

In 1957, Quanah, Cynthia and Prairie Flower were reburied on Chief’s Knoll. His red granite headstone—authorized by Congress and quarried from his beloved Wichita Mountains—reads:

Resting Here Until Day Breaks

And Shadows Fall and Darkness

Disappears is

Quanah Parker

Last Chief of the Comanches

Born—1852

Died Feb. 23, 1911

Standing at his grave, I am still a little perturbed.

Bridging two worlds, Quanah proved fearless in battle and in peace. He deserves more than a Renegade Roads written by a two-bit hack. He deserves a New York Times best seller.

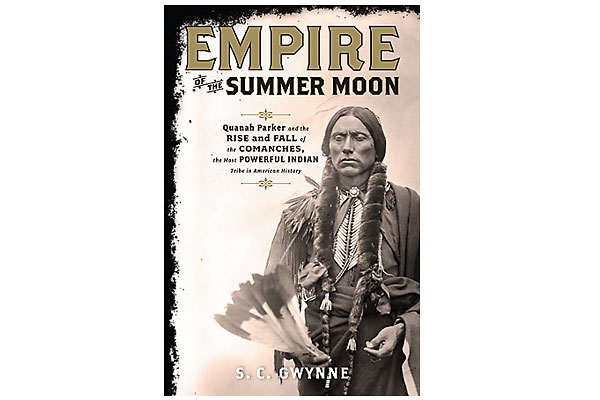

Wait. He has that now—S.C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History.

“I think he’s one of the greatest Americans I’ve ever heard of,” Gwynne told me before a book signing in Amarillo, Texas.

With the publication of this best seller, maybe more people will learn of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanche Nation and one really great American.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, circa 1890, standing in front of what looks to be the doorway of his Star House, a two-story frame house built for him at the behest of the founder of the 6666 Ranch, Texas cattleman Burk Burnett.

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions –

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –