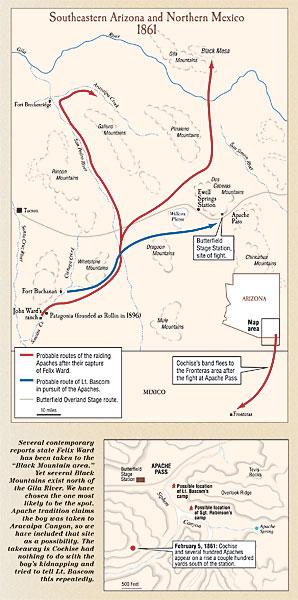

January 28, 1861

John Ward rides 11 miles to petition Fort Buchanan commander Lt. Col. Pitcairn Morrison to help recover Ward’s stepson Felix, who was kidnapped the previous day by Apaches.

Departing Fort Buchanan on January 29 to recover the boy, Second Lt. George N. Bascom leads a 54-man infantry unit (Company C, 7th Infantry) mounted on mules. John Ward rides with them to serve as an interpreter. Bascom’s column reaches the Butterfield Stage station near Apache Pass on February 3.

Summoned several times, Apache Chief Cochise finally shows up at Bascom’s camp on February 4 with his brother, three other males, his wife and two boys (one allegedly Cochise’s youngest son Naiche).

When soldiers try to hold the chief and his entourage hostage, in exchange for Felix Ward, Cochise and his brother cut their way through the back of the tent to break free. A slightly wounded Cochise escapes, while one Apache male is killed; the other six Apaches are captured.

In the evening, Apache signal fires atop the peaks surrounding the station blaze a request for immediate help.

On the morning of February 5, Cochise and several hundred Chiricahuas appear on a rise a couple hundred yards south of the station. After a brief demonstration, most of the warriors disperse and a white flag is unfurled.

A handkerchief from the station returns the signal. A warrior bearing the flag approaches to within earshot and yells out in Spanish that Cochise wants to parley with the soldier chief.

Bascom steps out into the open, along with Ward, Sgt. William A. Smith and Sgt. Daniel Robinson. They walk forward to meet Cochise and White Mountain Chief Francisco, along with two others.

Cochise demands the release of his relatives. Bascom responds he will release them once Felix is returned to his stepfather.

Robinson sees Apaches sneaking back into the draw below them.

Perhaps noticing the Apaches, three Butterfield men—James F. Wallace, Charles W. Culver and Robert Walsh—come out of the stage station.

Wallace sees the Apache woman Juanita (he’s rumored to have a romantic relationship with her). He joins her at the edge of a ravine and embraces her. She holds him tight until several warriors leap out of the ravine and drag him and Culver into the canyon.

Culver is shot in the melee but escapes. Chief Francisco yells to the warriors, “Aqui! Aqui!” (“Here! Here!”), pointing at Bascom and imploring his men to capture the officers.

Dropping the white flag, Bascom orders his men at the station to open fire. He and his party run out of the arc of fire toward the station.

Walsh is shot dead (some speculate by friendly fire), while everyone else, save Wallace, makes it to safety.

Cochise offers to exchange Wallace for the captive Indians on February 6, but Bascom insists on the return of the boy and the parley ends inconclusively.

On February 7, Cochise appears on a ridge and yells to Bascom that he now has three additional prisoners: Americans Sam Whitfield, William Sanders and Frank Brunner.

The previous night, his warriors attacked five wagons filled with flour bound for the mines at Pinos Altos, New Mexico. The freighters had gone into camp about two miles west of the station. The Apaches attacked them after dark, killing six of the Mexicans outright, while lashing two to the wheels and burning them to death. Cochise left a note stating he will return the next day to talk again.

The Apaches also attacked an eastbound stage that night, wounding the driver and killing two of the mules. Cutting loose the dead stock, the stage made it to the stage station and the relative security of the mini fortress.

The ground is white with snowfall from the previous night when 15 soldiers head out on February 8 to take the mules from the station to the spring to be watered.

While the men cover the springs from Overlook Ridge, they spy some 200 Apaches, jogging on foot and crouching low, singing a war song.

The soldiers open fire and divert the Apache’s planned attack only slightly, as the Indians overtake the ridge, capturing the herd and wounding several soldiers.

Bascom sends out a relief party only after he is assured this attack is not a feint. His soldiers, all on foot, engage the Indians, killing five. Mangas Coloradas and Geronimo allegedly fight in this battle.

Responding to the couriers sent out by Bascom for help, a column from Fort Buchanan enters the station on February 10 with three male Apaches they took as prisoners

after encountering them on their ride to the pass. On Valentine’s Day, First Lt. Isaiah N. Moore from Fort Breckenridge leads

75 dragoons into the station. Both of these arrivals are a relief to the besieged column.

On February 16, Moore, the ranking officer, sends out patrols to scour the hills. They search for three days. They initially find nothing (the Apaches apparently fled to Fronteras, Mexico). Then they discover the badly decomposed bodies of four human remains and the unread note Cochise had left on the bush.

Of the corpses, Wallace is identified only by the gold fillings in his teeth. Horrified at the gruesome torture of the men, the soldiers talk of taking revenge on the Apache captives back at the station.

When Moore’s party returns on February 19, the soldiers march six Apache prisoners to the graves of Wallace and the others, and hangs the prisoners, leaving them where Cochise will find their bodies.

The soldiers spare the lives of the two boys and Cochise’s wife, although Apache tradition claims their fate was decided in a card game.

This tragedy of bluster and miscalculation on both sides fuels a series of wars that will not end for the better part of three decades.

An Eyewitness Account

While Lt. Bascom was en route to Apache Pass on January 28, Sgt. Daniel Robinson came to the pass from the east, returning with a 12-man escort guarding a New Mexico supply train.

The Irish immigrant Robinson had enlisted in 1849. He served in Florida, Arkansas and Utah before arriving for duty in New Mexico and Arizona.

In the late 1880s, after he retired with the rank of captain, Robinson wrote down his eyewitness account of the Bascom fight; it ran in a truncated form as “The Affair at Apache Pass” in the August 1896 issue of Sports Afield.

Other than Bascom, Sgt. Robinson was the only eyewitness to record the events he witnessed. Included below is his first-person account of the “Cutting the Tent Affair” and other highlights:

“…I heard a shot at Bascom’s tent and saw Indians running off in different directions…. One of them was held by the sentinel’s bayonet, the other, Cochise, escaping, on whom the Interpreter [John Ward] fired a pistol and, it was said, slightly wounded the chief.

The other Indians cut their way through the Company tents in the same manner [as Cochise had]. One of them passed close to me, followed by a Sergeant, who had a musket in his hand. It seemed to be the intention of the Sergeant to capture him alive.

“The Indian frequently picked up stones and threw them at him defiantly. Finally, the Sergeant stopped long enough to load his piece. During this operation he lost sight of the Indian but pushed on.

“The next I saw was the Indian jump up from behind a rock, with his knife raised ready to strike as the Sergeant passed. The Sergeant wheeled around in time to save his own life by shooting the Indian dead.”

After Cochise escaped, Robinson and his men were ordered to strike their tents and move to the safety of the stage station. They moved the wagons along the southwest side of the building to form a basis for breastworks and rifle pits, and they also dug a trench and filled empty grain sacks with the dirt to use as additional breastworks.

Robinson participated in the parley on February 5, 1861, when he, Sgt. Smith, Lt. Bascom and Ward walked out, unarmed, to meet with Cochise and three other Apaches. Bascom and Cochise talked for about a half hour with “Cochise making a strong appeal for the release of the two [six] captive Indians,” Robinson noted. As the two were negotiating, Robinson wrote, “…I saw many Indians enter the ravine at a point below us carrying cedar bushes on their shoulders, which they generally used as cover while firing laying down.”

Station keeper Wallace “approached the ravine at a point above us…two squaws that were in the habit of visiting the station came out of the ravine and motioned to him in a pitiful and affectionate manner with hands raised.” When Wallace met the women, they held him fast as some of the warriors in the ravine sprang up and “seized and dragged him into it out of sight,” Robinson noted.

Three days later, on February 8, Robinson and several troopers left the stage station to guard and water the stock. Robinson and another soldier stood on a ridge above the herd, as the mules drank from the spring, when Robinson noticed a “large war party of Indians about 300 yards off coming down a ravine that led into the one we were on…. The Indians were on foot, bending low and moving rapidly, singing a war song.”

The Apaches “opened a plunging fire on us from the [opposite] ridge.” Robinson ordered the soldier with him to move higher on the ridge and the men at the spring to return to the station. As Robinson turned to follow the soldier, he wrote, “I was hit in the right leg, the ball entering on the outer side of my right leg near the knee, passed downwards and out above the ankle on the inner side. I could only move a few paces, and sat down under a little cactus bush and reloaded my piece…. I was in an exposed position and received some attention from them. The greatcoat I wore testified to that fact which contained many holes.”

Reinforcements from the station drove off the Indians, killing five. Robinson wrote that he recovered from his wound and lived to fight again.

Felix Ward Becomes Mickey Free

What happened to the boy Felix Ward? We know one thing—when he emerged as an adult to enlist with Gen. George Crook’s scouts at Camp Verde in 1872, he was clearly an acculturated Apache. As such, the soldiers at Camp Verde named him “Mickey Free,” after an Irish character in Charles Lever’s popular 1841 book Charles O’Malley, the Irish Dragoon. They often assigned humorous names to the Apaches; for instance, an Apache with a bad scar led to the moniker “Cut Mouth,” while a taciturn brave was dubbed “Fun.”

Author Allan Radbourne attempts to fill in the gaps of young Felix’s life in the 2005 book Mickey Free: Apache Captive, Interpreter, and Indian Scout. Drawing on interviews with Felix’s Apache relatives, Radbourne has patched together at least a hint of the boy’s transformation.

Family tradition maintains the boy was captured by an Apache band led by Beto, a former Mexican captive-turned-Apache; they lived in the Aravaipa Canyon area under Chief Eskiminzim. Those Apaches traded him for medicine to a White Mountain Apache shaman, who turned the boy over to the leader Nayundiie. Raised with Nayundiie’s sons, Felix learned to hunt and became a full-fledged warrior.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

At the start of the Civil War, Lt. George N. Bascom moved to the Rio Grande in New Mexico and was promoted to captain on October 24, 1861. The next year, he was killed at the Battle of Valverde, east of Santa Fe.

***

For the next decade, Cochise went on the warpath against any and all white people he encountered, killing and burning his way throughout southeastern Arizona and into Mexico. Inexplicably, he had time to “make peace” with Tom Jeffords and others. The chief was wounded twice—once in the leg and a more serious wound in the neck.

Tired of fighting, Cochise negotiated with Gen. Oliver O. Howard in 1872 to establish a reservation in the Chiricahua Mountains. Yet the younger members of his tribe still raided, so the government forced the tribe to move to San Carlos instead.

Cochise fathered two sons: Taza, who died while on a tour of Washington, D.C., and Naiche, who fought alongside Geronimo and lived until 1921.

Cochise supposedly died of cancer on June 8, 1874, in his beloved Dragoon Stronghold. His body, and that of his horse, was buried in a secret crevice that has never been found. In spite of his controversial reputation, the people of Arizona named a county after him a mere seven years after his death.

***

With the Union’s abandonment of various Arizona forts, John Ward and his family left their Sonoita homestead and moved to Tucson for protection. John worked as a glassblower.

In 1865, at age 59, he attempted to start another farm near Tubac. Two years later, Indians once again raided his farm, taking all of his stock “in broad daylight and whilst the animals were hitched to the ploughs.”

John never recovered from the $600 loss, and he died in October 1867. Neither he nor his wife ever saw

Felix again.

***

Recommended: Fort Bowie, Arizona: Combat Post of the Southwest, 1858-1894 by Douglas C. McChristian, published by University of Oklahoma Press.

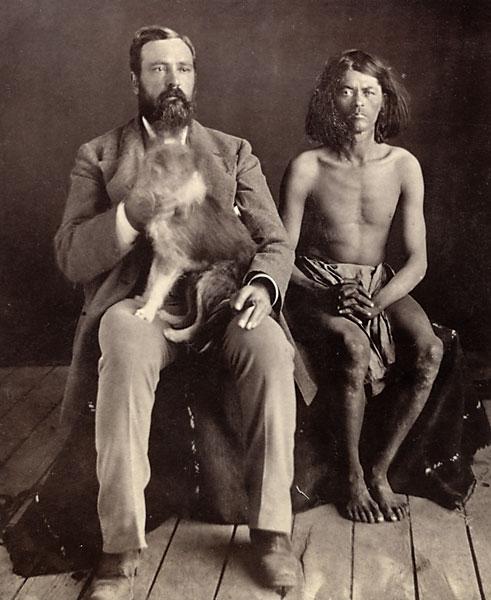

Photo Gallery

No known photos of Cochise exist, but contemporaries described him as a well-built man standing at five feet 10 inches (several inches taller than the average Apache). James Tevis, in charge of the Apache Pass stage station, admitted he did not think “Cochise ever met his equal with a lance.”

– Illustration by Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum–

– Courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum–