Many “what ifs” can be found in history.

Many “what ifs” can be found in history.

Certainly this was the case with the controversial Bascom Affair that took place 150 years ago. Had the zealous, young Lt. George Bascom respected Cochise and accepted his word, captive Felix Ward might have been returned to the military without further incident. Ward would have never earned acclaim as Mickey Free and, perhaps, the Apaches may have reacted in a different manner to the arrival of newcomers who flooded into their territory in the Victorian era.

Instead, Bascom’s brash actions spawned almost 30 years of violence and cost hundreds of casualties—both red and white—not to mention untold millions of dollars from the national treasury. The fact that the Civil War erupted in 1861, soon after the debacle, further fueled an already volatile situation. With the withdrawal of federal forces from most of the Southwest, “Mining came to a standstill; ranchers abandoned their stock; farmers fled their fields; and all moved to Tucson or left the [Arizona] territory entirely,” reported Odie Faulk in The Geronimo Campaign.

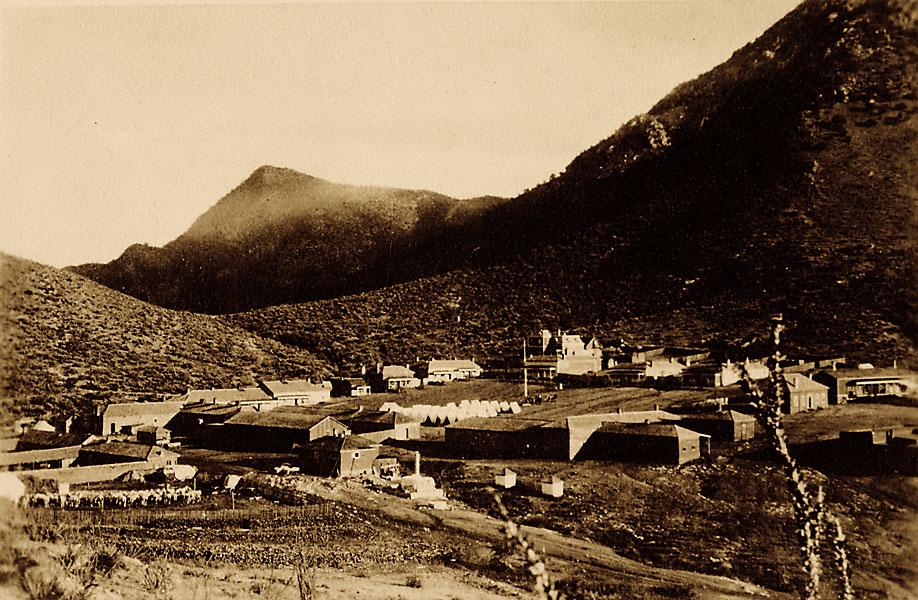

The arrival of Union volunteers in 1862 and the subsequent building of numerous outposts, such as Fort Bowie near Cochise’s stronghold, failed to quench the flames. Nearly a decade of hit-and-run encounters during the Civil War and immediately after left the region in chaos and the local tribesmen free to strike whenever and wherever they pleased.

In the early 1870s, efforts under the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant attempted a peace policy enlisting various religious denominations to oversee reservations that had been brought into existence to “civilize” the Apaches and other native peoples of Arizona and New Mexico.

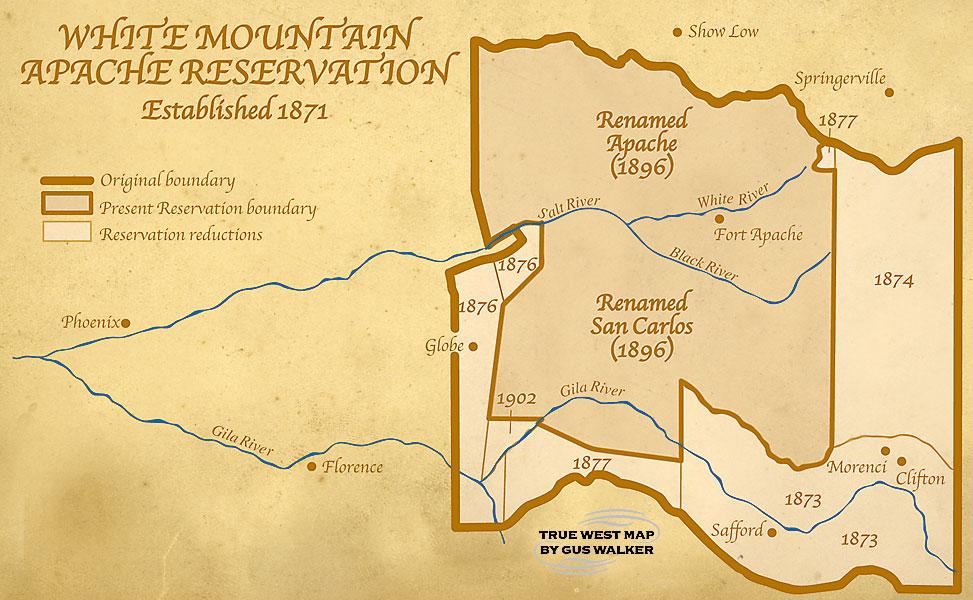

Cochise’s people were given land near their traditional range close to the Chiricahua Mountains in 1872, while others, such as the Yavapais, were rounded up and sent to a site in the Verde Valley in 1873. The Yavapais, in 1875, and the Chiricahuas, in 1877, would be forced to relocate again, along with several Apache bands, to a less than desirable home in San Carlos. Even if the peace efforts meant well, they were ill-fated and the Indians despised the reservations.

Concurrent with military and civilian officials’ attempts to offer the olive branch, a combat commander named George Crook arrived intent on bringing about an end to the fray. While he made considerable progress, he transferred to participate in the 1876 campaign, which included the devastating defeat of George Custer at Little Bighorn. With his departure, the highly mobile guerrillas kept up their resistance.

The border between Mexico and the U.S. became a combat zone. Apaches raided with impunity into Sonora, Mexico, as well as central and southern parts of Arizona and New Mexico Territories. Usually these were small firefights, but they made a stand in sizeable numbers in Arizona at the Battle of Big Dry Wash in 1882 and another engagement in Cibecue in 1881. In the latter instance, the Apaches even threatened the fort that bore their name.

Troop escalation and the return of Crook in 1882 brought about ever-increasing efforts to subdue the region. A force of 5,000 soldiers from the U.S. Army, which at the time totaled scarcely 25,000 officers and men, was deployed. The soldiers were sent to crush the remaining few dozen determined holdouts who refused to surrender. Led by one who was known to his fellow Bedonkohes as Goyahkla (“He Who Yawns”), but to the Americans and Mexicans by a name many came to fear, Geronimo, the struggle dragged on. Then, in 1886, Gen. Nelson Miles finally brought Geronimo to bay.

While this was not the end of the Apache Wars, it was the beginning of the end. Scattered incidents, which included strikes by the Apache Kid, continued into the early 20th century, yet the outbursts were minor in comparison to the bloodbath of an earlier era.

As part of the aftermath, many Apaches were shipped away as prisoners of war and remained so even after Geronimo’s death in 1909. Their lives were precarious, at best, as likewise proved true for most of their fellow native peoples who remained behind in the Southwest.

Nonetheless, the tragic tale of the Apache campaigns not only led to Geronimo’s emergence as an Old West legend but also gave rise to a litany of other characters who otherwise might have been relegated to little more than obscure footnotes. Some of the key players on both sides of this life-and-death struggle are worth recalling. They appear here as examples of a clash of cultures, which remains as compelling today as it was when bold front-page headlines of the late 1800s carried the chilling word “Apache.”

1861-1932 Timeline

January 27, 1861

Felix Ward is kidnapped by Apaches.

February 5, 1861

The Bascom-Cochise Affair ignites warfare.

July 15, 1862

Brigadier Gen. James H. Carleton’s advance column is ambushed at Apache Pass by a combined force led by Cochise and Mangas Coloradas.

July 27, 1862

Carleton arrives at Apache Pass with the California Column, and Fort Bowie is born.

January 17, 1863

Chief Mangas Coloradas, now about 70, is killed by gold hunters near Silver City, New Mexico. He is scalped, and his head is cut off and shipped back east, ending up in the Smithsonian, where it resides as a curiosity.

February 24, 1863

Arizona Territory is created out of New Mexico Territory, west of the 109th meridian.

April 30, 1871

At dawn, a combined force of 92 Papagos, 42 Mexicans and six white citizens from Tucson descend on the Apache rancheria at Camp Grant, killing 86 and carrying off 29 children. This becomes known as the Camp Grant Massacre.

December 28, 1872

A command under Capts. William Brown and James Burns traps about 100 Yavapais in a cave at Salt River Canyon. After the Indians refuse to surrender, the cave is bombarded with bullets, which ricochet from the sloping roof and annihilate the defenders.

June 8, 1874

As he predicted, Cochise dies at 10 a.m. in the east stronghold of the Dragoons. News of his death spreads throughout the surrounding rancherias, and the wailing of grief-stricken Apaches can be heard all day and night.

July 31, 1875

The White Mountain and Coyotero tribes are uprooted from their Fort Apache reservation and moved to San Carlos. (The Tonto Apaches and Yavapais were moved to San Carlos in February.)

May 12, 1879

In a surprise ruling for “Standing Bear vs. Crook,” a federal court declares “an Indian is a person.”

August 21, 1879

A party from Silver City, including a judge and the prosecuting attorney of Grant County, arrives on the Mescalero reservation for a hunting and fishing trip. Victorio assumes the party has come to arrest him. The entire Warm Springs band breaks out and heads for the Mexican line. They leave a wide swath of blood and devastation in their path.

Fall 1879

Tired of the warpath, Geronimo tells the army he has come to “live in peace.” Terms are agreed upon without difficulty, and the band returns to San Carlos.

October 14, 1880

Victorio and his band are ambushed at Tres Castillos in Chihuahua by a large Mexican force under Col. Joaquin Terrazas. Including Victorio, 78 Apaches are killed and scalped for the bounty, which reportedly adds up to $50,000. Only 17 Apaches escape.

August 29, 1881

As the commanding officer of the 6th Cavalry at Fort Apache, Col. Eugene Carr, with 93 men and 23 Apache scouts, arrests Apache medicine man Noch-ay-del-klinne at Cibecue Creek. The medicine man submits quietly, but his followers are quite upset after several confrontations. A fight breaks out, and several are killed. Some Indian scouts defect and join the hostiles.

September 30, 1881

Ration day at San Carlos: Geronimo and the Chiricahuas are in line when four companies of cavalry under Maj. James Biddle advance on them. Spooked, most of the Chiricahuas bolt for Mexico.

October 2, 1881

Troops A and F of the 6th Cavalry catch up to Geronimo near the west end of the Pinaleno Mountains. Juh and Geronimo fight a delaying action, sending their women, children and cattle over the flank of the foothills while a rear guard steadily fires from a rocky knoll. The Chiricahuas sweep south across the plains, stealing $20,000 worth of Henry Clay Hooker’s prize horses.

July 1882

Widely castigated in the press for its failure to capture Geronimo or any hostile ringleaders, the Army changes its lineup: Gen. Orlando B. Willcox is relieved of his Arizona command and sent to the Department of the East; Gen. George Crook, who does not assume command until September, replaces him.

July 17, 1882

The Battle of Big Dry Wash results in the death of 21 Apaches, and it marks the last major battle between Apaches and troops on Arizona soil.

May 1, 1883

Crook and a large expedition invade Mexico to track down Geronimo.

November 23, 1885

Lieutenant James Lockett, the new commander at Fort Apache, telegraphs Crook that he is pursuing a small band of hostiles seen within four miles of the fort. The line is cut, and Crook is left in the dark.

November 27, 1885

After repairing the telegraph line, Lockett wires Crook, stating “it seems probable” the hostiles have slain 11—two women, four children and five men—all White Mountain Apaches. The group, led by Ulzana, is allegedly bent on punishing any Indians who do not take to the warpath and frightening others to join in the battles. (This event inspires the 1972 movie Ulzana’s Raid.)

December 27, 1885

A savage three-day blizzard blankets the Chiricahua Mountains, making Ulzana secure from pursuit when he enters Mexico. He has traveled 1,200 miles, killed 38 people and stolen and worn out 250 horses and mules. Twice dismounted and nearly captured, Ulzana loses but one man.

January 9, 1886

After an 18-hour march, Capt. Emmet Crawford and his scouts sneak up on and attack a Chiricahua camp deep in the Sierra Madre. In the morning twilight, almost all the hostiles escape, but the troops capture their entire herd and supplies. Realizing their ultimate defeat, the Apaches send a woman to strike a deal with Crawford. A meeting is set for the next day. With a settlement at hand, Crawford is on the verge of being the hero of the day.

January 10, 1886

Led by Tarahumari Indian scouts (longtime enemies of the Apaches in Mexico), a Mexican command attacks Crawford’s camp. After 15 minutes of sharp fighting, Crawford runs out 50 yards in the direction of the Mexican line and pleads with them to stop firing. Crawford is killed in an exchange of fire.

January 12, 1886

Taking Crawford’s place, Capt. Marion P. Maus moves his camp four miles to avoid contact with the Mexican troops. Two Apache women arrive, and a council with the hostiles is arranged.

March 15, 1886

The hostiles signal their approach to the Army and arrive in small groups by March 19. Maus cannot induce them to cross the border. The Apaches insist that Crook meet them without soldiers. Geronimo names the place for the negotiations Canyon de los Embudos (Canyon of the Funnels).

March 24, 1886

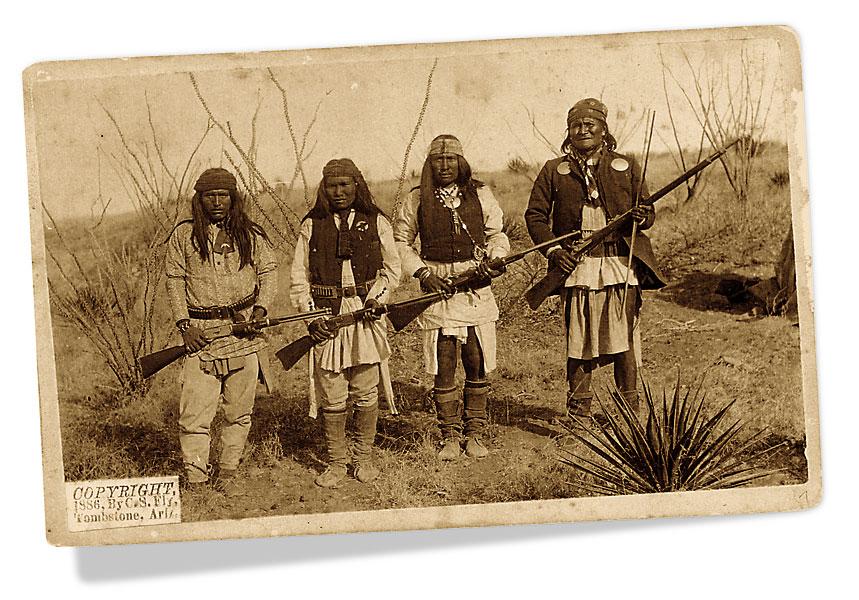

Crook leaves Fort Bowie with a detachment of troops, scouts and packers. A photographer from Tombstone, C.S. Fly, gains permission for him and an assistant named Chase to join the procession.

March 25, 1886

Crook meets Maus and Geronimo at Canyon de los Embudos “in the shade of a large cottonwood and sycamore trees,” notes Crook’s aide Capt. John Bourke. As the parley begins, C.S. Fly frantically sets up his camera and asks the participants to turn this way and that. (Capt. Bourke later notes that Fly had a “nerve that would have reflected undying glory on a Chicago drummer.”) Bourke makes a verbatim record of the conference. After the Apaches agree to surrender, a whiskey trader sells hooch to the Apaches and Geronimo bolts for Mexico.

April 1, 1886

After much soul searching, Crook sends Gen. Philip Sheridan a detailed defense of his actions, ending with the following message: “I believe that the plan upon which I have conducted operations is the one most likely to prove successful in the end. It may be, however, that I am too much wedded to my own views in this matter, and as I have spent nearly eight years of the hardest work of my life in this Department, I respectfully request that I may now be relieved from its command.” It is April Fool’s Day.

April 2, 1886

General Nelson Miles is assigned to replace Crook.

April 5, 1886

Crook is informed that the terms of surrender he has accorded the hostiles have been “disapproved” by President Grover Cleveland and that the Indians now in custody are to be sent to Fort Marion in Florida.

September 4, 1886

Geronimo, Naiche and their families surrender to Gen. Nelson Miles, and they are shipped to Florida. The price of cattle ranches in Arizona doubles.

October 9, 1886

The Army discharges the last of the Apache scouts from the Geronimo campaigns; most of them are sent to Fort Marion to join the other prisoners.

1891

The number of Indian scouts serving the military drops to 150, with 50 of them remaining in Arizona, mainly to patrol the U.S./Mexico border.

March 5, 1905

Geronimo is invited to ride in President Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade.

February 17, 1909

Dying of pneumonia, Geronimo closes his eyes at 6:15 a.m. and finally surrenders.

1932

Not all Apaches cease warfare after Geronimo’s imprisonment. Raids in Mexico continue (most notably, the brutal murder of Maria Fimbres and the kidnapping of her boy in 1927) until 1932, when vaqueros track down and kill some of the last holdouts.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Fort Huachuca Museum –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

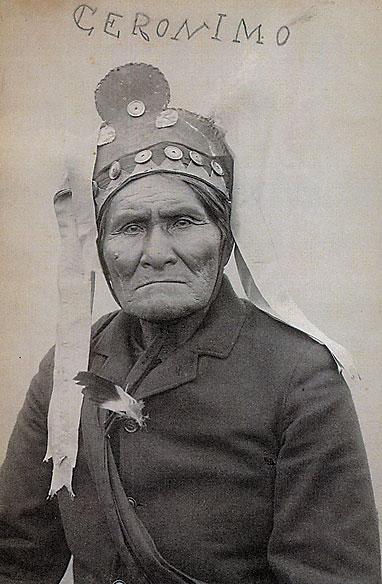

After surrendering in 1886, the Apache leader Geronimo becomes quite in demand at expositions, parades and fairs across the nation.

The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis invites Geronimo to attend for $1 a day, but a promoter offers him $100 a month, which he accepts.

Geronimo stays at the fair for six months. Two armed soldiers stand beside Geronimo, everywhere he goes. This creates the aura that the warrior is still dangerous, even though he is 76 years old. He later writes: “I sold my photographs for 25¢, and was allowed to keep 10¢ of this for myself. I also wrote my name for 10, 15 or 25¢, as the case might be, and kept all of that money. I often made as much as $2 a day, and when I returned, I had plenty of money—more than I had ever owned before.”

Invited to ride in Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905, Geronimo is given a check from the Army for $171. Geronimo takes the check to Lawton, Oklahoma, deposits $170 in his bank account and leaves for Washington, D.C., with $1 in his pocket. He is not in need of cash—all the way to the nation’s capital, at every stop of the train, he sells his autographs as fast as he can write out his name.

The budding capitalist is so successful, by the time he dies, in 1909, he has amassed $10,000 in his bank account. Imagine what Geronimo could have done on Wall Street today.

An actual photograph sold and signed by Geronimo (the soldiers at Fort Sill taught him how to sign his name).

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

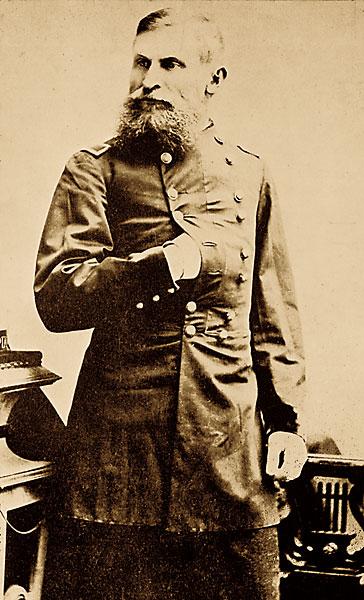

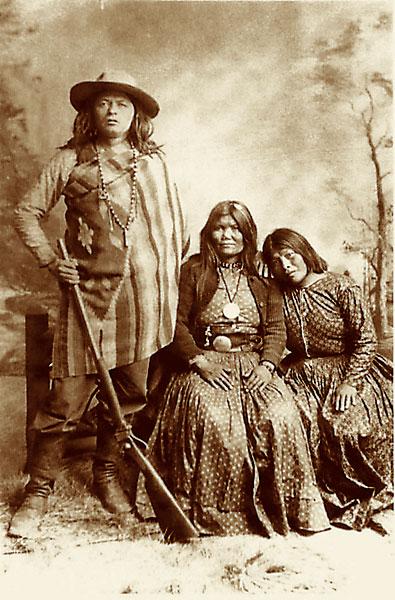

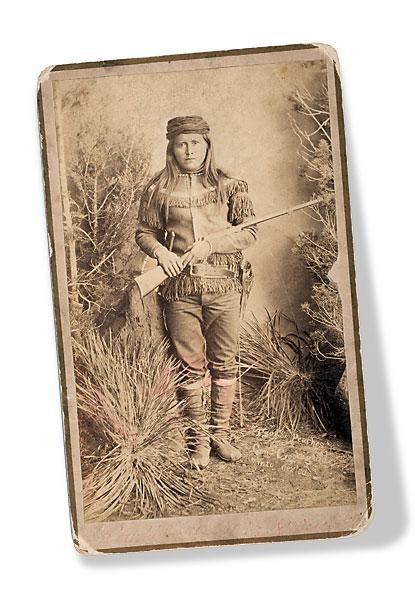

After his graduation from West Point, Marion P. Maus joined the 1st U.S. Infantry regiment. But this conventional assignment ended when he joined the Geronimo campaigns under Capt. Emmet Crawford and his battalion of White Mountain Apache scouts consisting of Companies A, C and D. After Crawford’s unfortunate death in 1886 at the hands of Mexican troops, Maus assumed command of the battalion and was present with his men when Geronimo met with Gen. George Crook. Maus is seen in this photo, on the opposite page, standing with a rifle.

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Marc Simmons –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy Fort Huachuca Museum –

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions –