Bonanza is so much a part of our cultural history and our TV past that its familiarity disguises the fact that the show is genuinely odd.

Of all the gun-toting lawman and loner shows that ate up the finite broadcast space of TV’s Golden Age, Bonanza drew upon standard TV Western motifs the least. In fact, the show, like actor Michael Landon’s later series, Little House on the Prairie, has more in common with the Family Saga genre than the Western.

The networks were looking for novel approaches to the Western, which, at the time, was its most successful genre. Yet the idea of fashioning a series about a Civil War-era land baron and three-time widower Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene) and his three greatly dissimilar sons, Hoss (Dan Blocker), Adam (Pernell Roberts) and Little Joe (Landon), set up high on the eastern reaches of Lake Tahoe, is a remarkably curious one.

In the same way that John Meston guided Gunsmoke, Herb Meadow and Sam Rolfe drove Have Gun, Will Travel and Gene Roddenberry fashioned Star Trek, Bonanza was the brainchild of David Dortort. While writing scripts for a variety of TV series during the early 1950s, Dortort was producing a half-hour, black-and-white Western, The Restless Gun, when he found out that NBC was looking to produce an hour-long Western. Dortort reached back into a place and time in American history that had once inspired another show he wrote, in 1953, called “Man of the Comstock,” for NBC’s Firestone Theatre. Through his connections, luck and spectacular timing, he managed to sell NBC on Bonanza.

To Dortort’s credit, Bonanza remained hugely popular throughout its 14-year run. The desertion of one of its four principles (Roberts) and the death of another (Blocker) finally closed down the shop.

One of the surprises that comes from viewing the early episodes of Bonanza is how progressive the show was. Talk, and there’s a lot of it, almost always took priority over action, as did reasoning over violence. The series most often was about avoiding and resolving conflict, although no Western could survive an entire hour without a donnybrook or two.

These early episodes make it clear that the most immediate concern of the Cartwright family was in keeping people, especially hustlers, entrepreneurs and assorted riffraff, off their propery. An interesting secondary concern was in maintaining a safe environment for the local Paiutes who were inclined to poke holes in folks when crossed. Trouble with the Paiutes actually did play a significant role in the Comstock Lode region of Virginia City, Nevada, during and after the Civil War.

The antagonism between the Cartwrights and the community was a story element that had to be corrected early on because it was counter-productive for the health of the show. Bonanza took a while to settle into its greatest strengths, but to the show and Dortort’s credit, it did exactly that.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Bonanza, which aired on NBC from September 1959 to January 1973, the entire first season is available for the first time on DVD, either as two separate volumes or banded together into one. It’s a little silly that Paramount didn’t just pony up and put a handsome box together for the eight discs, but who can fathom marketing?

The quality of the picture and sound on these discs is just great—the studio outdid itself in that department. You’ll also find many extras, from interviews to photo galleries, in the collection.

What is unusual, and very welcome, about this collection are the notes on the inside jacket that give episode, plot and cast information, identify the director and writer, and tell the reader where and when the episodes were filmed. Credit for all this goes to package producer Andrew Klyde, who serves as Bonanza’s principal lawyer for merchandising and licensing. More important, Klyde is devoted to the series and gives presentations at Bonanza events all over the country.

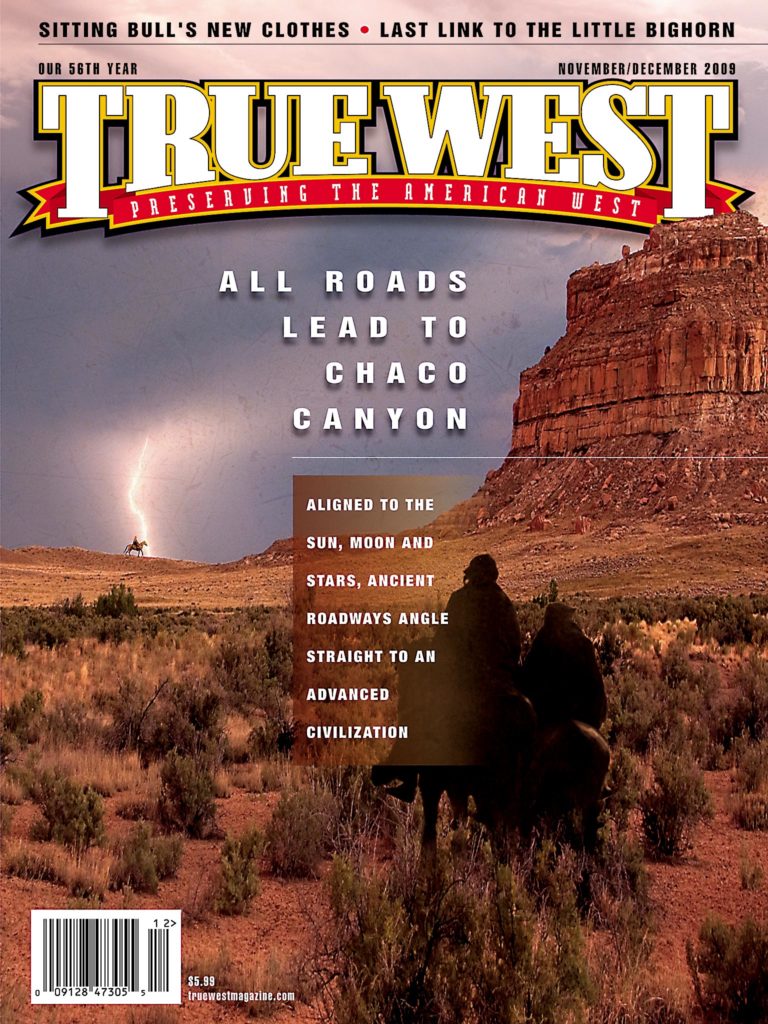

True West spoke to Klyde just a few days before he was scheduled to appear at an event at Lake Tahoe, only a few minutes from what would have been the Ponderosa’s westernmost border.

True West: Did the location information and shooting dates in the liner notes come from you?

Andrew Klyde: I lobbied, I cajoled, I persuaded, I insisted that I have that stuff in there. Almost as important, the big, big boss was the one who said, “Okay, Andy. If you believe in it, I’ll put it in.”

I really wanted the episodes to be in chronological order on the discs, in the order they were made, not in the order in which they aired, which was at the time just the whim of some NBC programming guy who had to consider what CBS and ABC were doing that night. I lost that one. They said, “We have to put them on the disc in the order in which they were presented, but we’ll let you write in the filming dates.”

Then they copped out, and they put this little disclaimer way on the bottom that states filming dates are approximate. I said, “They’re not! They’re not approximate. I have shooting information and production reports and I know exactly—.” So, uh, “Okay, we’ll put it in there.” Then I said, “I want to be able to put locations, when known, and interesting credits of guest stars, when known,” so I did it all in increments. I was told things like, “Well, if you can get this to us by 3:00 this afternoon, if there’s room, we’ll put it in.” [Laughs.]

Everything was a battle. People in the legal department were saying, “Well, we’ve never done this before. We really can’t do it now. It’s just not done.” Well, that sounds like a good reason not to do something, because it hasn’t been done before. [Laughs.]

I have to say, I’m really grateful that Ken Ross [executive vice president of CBS Home Entertainment], who is the head of the whole operation, said, “Okay, do it.” I hope that others appreciate the work that I put into it ’cause that’s what I would want to see.

In the DVD collection, you have included Dortort’s historical drama “Man of the Comstock,” and it’s described as the “genesis of Bonanza.”

I knew it would be cool to include that because David Dortort has been telling me about it for years. He’s the one who described it as the genesis of Bonanza. But I’d never actually seen it—nobody had ever seen it—and I had to take a chance that it wasn’t terrible. It’s definitely a curiosity piece, and I think it deserves to be there.

Where did you find it?

It was extraordinary what I had to go through to find it. I looked everywhere, and nobody had it. Finally, as an afterthought, I decided to check the Library of Congress because shows were sometimes deposited there for copyright registration. Not only did I find it there, but they had an original 35mm nitrate print. I had no idea they made nitrate prints, and it would have been no good, except that they had actually made a safety print in 2006.

How did the series change over time?

As an observer and a historian and archivist, I can say you can distinguish between periods. Bonanza enthusiasts like to call the first six years from 1959 through 1965 as the “glory years” because Pernell Roberts was still in the cast. After Pernell left in 1965, the dynamic changed. I don’t think the quality decreased at all. In fact, I think you could argue the opposite, that many of the strongest, hard-hitting, controversial, thought-provoking shows, which, incidentally, were the kinds of shows that Pernell Roberts yearned to do, were produced in abundance after he left.

What’s responsible for the change?

The changing mores in society at the time. The turbulent quality of the era allowed screenplay writers to say things that were a bit more thought-provoking and topical and controversial, whereas in the early days, David Dortort tried to produce those kinds of shows but was met with fierce resistance by the network executives and censors determined to put out a product that offended no one, or at least the smallest number of people.

You could sort of get away with things if you were working on a period piece like Bonanza, or a Science Fiction series, which is why Rod Serling retreated from the anthology show format to the escapist form of Fantasy and Science Fiction (The Twilight Zone), because you could tell fables and allegories. To some extent you could do that with the Western, but it was harder. For example, Bonanza had a story called “The Weary Willies,” which featured Richard Thomas as the head of a band of ragtag Civil War veterans that were having trouble adjusting to society, and they were ostracized and chased out of all the towns they went to throughout the West. At the same time, in contemporary U.S. history, you had the returning Vietnam War veterans who were not getting the hero’s welcome that they felt they deserved. That was an example of a story that you could get away with by setting it 100 years in the past.

I was surprised to discover how much of a role conservation played in these early shows.

It’s a cliché perhaps to say that the series was ahead of its time because obviously those concerns were already there, otherwise the writers wouldn’t have written them in. But I guess they weren’t as widespread, and as well known, as they came to be later. I guess that’s part of the formula that contributed to the show’s enduring appeal over generations and so much time.

The name Bonanza had a kind of double meaning for David Dortort—because he used the common definition of bonanza to describe the riches below ground—the Comstock Lode, the silver and gold in the area they discovered there at the time—but it also refers to the riches of the land itself, the trees and the water and the livestock. That was a sort of bonanza for the Cartwrights, who were more environmentally conscious. Ecology and conservation and preservation is a theme that’s prevalent throughout the whole history of the series.

The Ponderosa was like the fifth character in the series.

The Ponderosa, the Ponderous Pine trees—. David Dortort originally envisioned the Cartwright ranch as having the name the Panamint.

Which comes from where?

It’s in the area, Panamint, and it comes from, well, you “pan all day, and you make a mint.” But that [title] didn’t really grab him or anybody else. So he was up in one of his late night writing sessions because he wrote the pilot under terrible, arduous conditions—.

Why is that?

In late 1958 NBC executives had decided that they were ready to produce something in-house, feeling they could do as good a job as an outside provider. It was the tradition at the time to get programming from outside, like Warner Brothers or Universal. But CBS had had some success with Perry Mason, which was produced in-house. So the NBC executives felt they should be allowed to try the same thing. They finally received permission from their superiors on the East Coast, and their instruction was, develop a one-hour program, and make it a Western; a Western, obviously, because it was the most popular genre, and one hour because the one-hour format was becoming increasingly popular. The half-hour program had been dominant for most of the decade, The Honeymooners, I Love Lucy and the most successful Westerns, Gunsmoke, Wanted: Dead or Alive, The Rifleman. But Wagon Train and Maverick were one-hour shows that were doing well, so they decided to put together a one-hour show and started soliciting ideas.

A fellow named Alan Livingstone was the head of the programming department. That’s a name that should be much better known than it is because he was responsible for what I like to call the “three B’s [Bozo, Beatles, Bonanza].” He created the iconic children’s clown character Bozo. After he left NBC, he became president of Capitol Records and agreed to pick up the Beatles, over the protests of his staff. But he also was the guy who said yes to David Dortort when he came in to make a pitch for a one-hour Western that told the story of three brothers and their father who owned and operated a cattle and timber ranch near Virginia City in the time period just before the Civil War and the [1859] discovery of the Comstock Lode.

But Livingstone’s associate was a fellow named Fred Hamilton, and it was really Fred who was David Dortort’s champion. The problem was, although they very much liked his concept, Dortort was under contract to do The Restless Gun for Review, the television arm of MCA and Universal. So he couldn’t actively produce the new project, but he could write it. So he would produce The Restless Gun during the day, and write what became the pilot for Bonanza in longhand at night in the office of Fenton Coe, NBC’s head of production on the West Coast.

Fenton Coe had a wonderful executive secretary named Joan Sherman (she was an interesting character, by the way; her father was the manager of Abbott and Costello). So David and Joan were working together in one of their late night sessions, and he would hand his legal pad to Joan, who was the fastest typist in the West, and she was sort of pausing. They weren’t happy with “Panamint.” She, being a bright gal, said, “Tell me a little bit about where the Cartwrights lived.” And he said, “It was nestled along the eastern shore of Lake Tahoe in the Sierra Nevada Mountains where these magnificent Ponderosa Pine trees dot the landscape.” She asked, “What kind of trees?” And he said, “Ponderosa Pines.” And she asked, “Why don’t you call it the Ponderosa?” And he said, “Eureka!”

Dan Blocker [Hoss], bless his heart, gave her an inscribed photograph, which said, “To Joannie, I hereby dub you the Madam of the Ponderosa, love Dan’l.”

Bonanza was the first hour-long color series. Whose idea was it to shoot the show in color?

That partly depends on who you ask. The instructions from New York were to make it a one-hour show and to make it a Western, but there were no instructions to shoot in color. That came later, and I believe that what probably happened was that David Dortort was enamored of the Lake Tahoe area; he had taken his family there on vacations. And he was always a student of American history, specifically Western history, even though he was born in New York and grew up in Brooklyn. But he had a great love for the West and visited a lot of the great national wonders, including Lake Tahoe. Again, he had an ally in Fred Hamilton, who had the ear of his boss Alan Livingstone. Fred Hamilton was very close friends with Robert Stack, of Untouchables fame, and Stack had a vacation home at Lake Tahoe. So between them all, they were all very familiar with, and in love with, the Tahoe area. It follows that they’d want to shoot in color. It just cries out to be preserved in living color. So I think what happened was, David, perhaps at his initial pitch or shortly thereafter, made a point of suggesting they shoot the show in color. The initial reaction was, that’s going to cost a lot of money, but, you know, the parent company, RCA, was in the business of making color TVs, after all.

Lorne Greene has said, that if it were not for the fact that the pilot was shot in color, it probably wouldn’t have gotten on the air. What he meant by that was, candidly, the pilot episode wasn’t really very good.

The reason it was not a great example of the series is because it was really rushed, and the [actors] were handed their scripts hours before filming started.

The NBC executives had seen two other color pilots and rejected them both, but they loved the way Bonanza looked. That’s because the director of photography was Bert Glennon, who was John Ford’s cinematographer and one of the all-time greats.

Has Bonanza ever received criticism for its portrayal of the pre- or early-Civil War era?

I know that Bonanza has come under some criticism for the inaccuracy of the Cartwrights’ weapons, but that definitely isn’t true of this first season. Dortort and company tried very hard for authenticity. For example, they used Henry rifles and authentic Colt 1860-issue revolvers. Later they switched to an 1875 version because they were lighter and less cumbersome.

I remember a conversation I had with Michael Landon once, and I told him I could date a photo of the series by the costumes they were wearing in the picture. He said, “I can tell by the weapons.” He went on to give me a lesson on the accuracy of the guns they used in the show.

What brought about the shift away from the antagonistic relationship between the Cartwrights and the Virginia City community in the early episodes?

There was an important evolution after about the 13th show. Lorne Greene said, in subsequent years, that he and the others approached the producer and said, “Why are we always pointing a gun at someone and saying, ‘What are you doing on the Ponderosa,’” which actually happens in the very first episode, when Yvonne Decarlo was hired to lure Little Joe off the ranch for nefarious reasons. Lorne’s attitude was, we should be making nice, not pointing guns.

So there was an important reversal of approach, and the Cartwrights, specifically Ben, became more benevolent and open. There was an early show [“Blood on the Land,” February 1960], which depicted a direct conflict between Ben, who was old school get-off-my-land-or-I’ll-kill-you, and new school Adam, who said maybe we shouldn’t be so harsh or be so quick to take the law into our own hands. That was something of a turning point in the series.

Dan Blocker amazingly commuted to the Bonanza set from Switzerland. Did he move his family to Europe because of his opposition to the Vietnam War?

I don’t know that it was entirely because of Vietnam or more because he wanted his children to grow up away from Hollywood and the celebrity circus. Certainly he objected to the Vietnam War and protested whenever he could.

They all shared that political sensibility. In 1963 they were scheduled to make a public appearance at an outdoor arena in Jackson, Mississippi, and they were told that the seating at the event was segregated. Blocker sent a telegram that said if the seating policy wasn’t changed, he would not be going. The reply was that they would not change the policy, and if he doesn’t go they’ll sue him for breach of contract. So shortly thereafter he sent a follow-up telegram saying he was not going, and the others all sent telegrams saying that they would not be going either. It made news at the time, and it started a trend. I talked to a fellow who represented people like [Gunsmoke’s] Ken Curtis and Amanda Blake and Milburn Stone, and other actors who would do the state fairs and rodeo circuit, and they all started saying that they’re not going to perform anywhere with segregated seating.

In 2001, the Bonanza prequel Ponderosa aired, and a Gunsmoke movie is currently in the works. Is anyone interested in making a Bonanza film?

Well, it’s a business where if something is perceived as successful, you’re immediately going to have a stampede of imitators. Not only have there been announcements of remaking Gunsmoke, but also The Big Valley. So I’m sure that interest in Bonanza is there, but whether anything will happen or not, I don’t know.

I think that probably the best way to catch the lightning in the bottle is to do what Dortort did with Ponderosa. You don’t try to duplicate the tremendous charisma and appeal of the actors who played the original, mature Cartwrights because that’s just impossible. But you can try, to use the current parlance, to reboot them. Still, I don’t think I can imagine any Hoss who isn’t Dan Blocker.