– All Images Courtesy True West Archives –

The whole story of the Alamo is of men willing to die but not to obey.

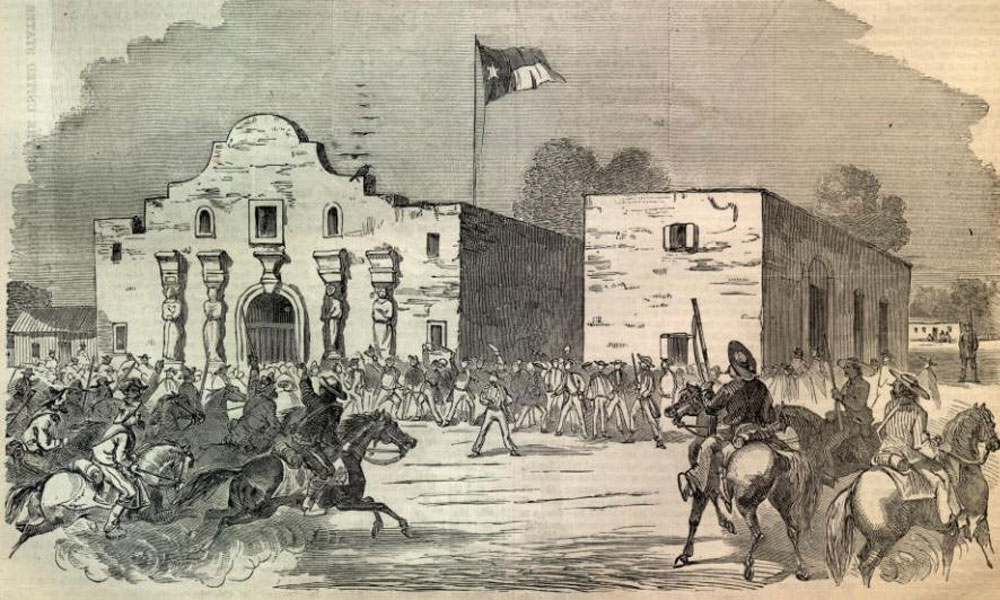

The main battle of the Alamo was in defense of the outer walls. After the Mexicans scaled them, the fiercest fighting was at the long barracks. The final stand of the defenders was in the chapel, the roofless walls of which stood 22 feet high and four feet thick. The debris of the fallen roof had been mounded up to serve as a platform for three twelve-pounder cannons. Fifteen to 18 other cannons were mounted at strategic positions along the outer walls. The flag did not float from the church but from a kind of tower room at the southwest corner of the “long barracks.”

Everybody knew that Santa Anna was coming, but reports of his coming had been arriving for such a long time that every morning everybody considered that it would be another day, maybe weeks, before he arrived. In February, Mexican families began leaving town for the country. It was not the season for Comanche raids and threats that kept Mexican settlers huddled together most of the year.

On February 22, Americans saw carts carrying Mexican goods and families out of town in all directions. Travis was very uneasy. He kept a lookout in the tower of San Fernando Church.

On the morning of February 23 the lookout rang the bell violently. He said that he had seen cavalrymen to the west, the sun glinting on their spears and that when he rang they disappeared into the brush. He could not show anybody what he said he had seen, and was discredited by men who did not want to believe facts. Dr. John Sutherland and John W. Smith, who had horses in a corral attached to the barracks, got permission from Travis to ride out on a scout. When they reached the crest of a hill about a mile and a half from the church, they beheld on prairie land beyond 1,200 or 1,500 cavalrymen, according to their estimate, forming in line of battle, their commander riding up and down in front of them waving his sword. They wheeled their horses and broke in a run for town. The sentry in the bell tower understood and began ringing furiously.

While all was movement within the fortification, Crockett stepped up to Travis and said, “Colonel, assign me to some place, and I and my Tennessee boys will hold it.” Travis assigned him a picket stockade running from the southwest corner of the old church to the rock wall.

By three o’clock that afternoon Santa Anna was flying a red flag from the main plaza and had some of his batteries planted. Contrary to common belief, the Texans did not fly a Lone Star, but the tri-colored (red, white and green) Mexican flag with “1824” stitched across the white stripe.

At the sight of the red flag, Travis ordered a discharge of artillery toward it out of range. About the same time, Bowie received a report that the Mexicans had sounded a parley. He sent out a note by a messenger bearing a white flag to inquire if a parley was desired. The answer, signed by Santa Anna’s aide-de-camp, was that the only recourse for rebellious foreigners wishing to save their lives was to surrender unconditionally. This was probably Bowie’s last official act. The next day he was helpless.

As soon as Travis could get his men together, behind the walls of the Alamo after the arrival of Santa Anna’s forces, he made them a no-surrender oration. He sent Dr. John Sutherland and John V. Smith to Gonzales to plead for men and provisions. “We have 150 men,” the hasty note reads, “and are determined to defend the Alamo to the Last.”

That night and the next, Texans demolished jacales (cabins) within reach along the acequias (irrigation ditches) and dragged in wood for fuel. They had been dependent upon an acequia for water.

On February 24, Travis sent out the most heroic message in the annals of North American war. One imagines that he spent hours of the cannon-shaken night composing it; it was not addressed to the futile political authorities who had so often been besought, but—

“To the People of Texas and All Americans in the World-Fellow Citizens and Compatriots: I am besieged with a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. I have sustained a continual bombardment and cannonade for 24 hours and have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded or [sic] surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, and our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call upon you in the name of liberty, of patriotism and everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily and will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due his own honor and that of his country. VICTORY OR DEATH!”

Travis’s main hope was in Fannin, stalled in his Matamoros hallucination at Goliad, where he occupied a walled-in mission. It stood on the San Antonio River, about 95 miles southeast of the Alamo. He had been receiving American volunteers and some supplies through Copano, a small port no longer extant. He had around 500 men under his command, some of them away on horse-hunting expeditions under officers as fatuous and unrealistic as he was and no more military in taking orders.

A week before Santa Anna hoisted the red flag over the main plaza in San Antonio, Travis sent Bonham to plead with Fannin for reinforcements and for amalgamation of the separated forces. Bonham did not return until the day Santa Anna arrived. He brought a conditional hope. Until almost the end of the siege, couriers, by following brush-lined irrigation ditches, passed in and out of the fort unintercepted.

On February 27, Bonham again left for Goliad, with orders to return by way of Gonzales and try to spur on forces from that place. Fannin finally started for San Antonio, but three of his wagons broke down, and he returned to the mission-fort at Goliad, presumably to wait until the ravens dropped serviceable oxen down to pull him out.

On March 3, after six days of hard riding, Bonham got back to the Alamo. Another man, maybe two men, rode with him until they came within view of the besieged fort. Here the man, or men, with Bonham said that to advance farther would be suicide. Even if they got inside, they were doomed. Bonham rode on alone. He had a white handkerchief tied as a band around his hat—a sign of recognition that had been agreed upon by him and Travis. The gate was open as he dashed up “on a cream-white horse all in a foam.” The hour was 11 o’clock in the morning. The Mexicans seemed willing to let in anybody who wanted to enter the trap.

Two days before, on the night of March 1, 32 Texas citizens from Gonzales had been piloted into the fort by John W. Smith, the messenger who went out with Dr. Sutherland the day Santa Anna arrived. Smith went back to Gonzales for more men. When he returned the second time, Dr. Sutherland and the small company with him saw an advance guard of Santa Anna’s soldiers moving toward them, heard no cannon and knew the Alamo had fallen.

The 32 Gonzales men were the only enforcements received by Travis. They gave him a total of 180-odd men. “Only the cries of their famished children and the smoke of their burning buildings will arouse the settlers,” Travis wrote. About the same time, now in futile desperation, Fannin wrote: “I have but three Texas citizens in the ranks, and tho’ I have called on them for six weeks, not one arrived… If I am lost, be the censure on the right head, and may my wife and children and children’s children curse the sluggards forever.”

On March 4, unknown to the Texans, Santa Anna called a council of war to consider assault on the Alamo. General Cos, who had returned to Texas in violation of the terms of his surrender at San Antonio, General Castrillon and others advised awaiting the arrival of two 12-pounders expected on the seventh before making an assault. Santa Anna already had more than 5,000 men at San Antonio. He dismissed the council without announcing a decision. An unusually heavy bombardment was kept up all day.

By two o’clock on March 5, a Saturday, Santa Anna had issued confidential orders to his subordinates to begin the assault at four o’clock the next morning. It was to be made by four columns, one to each side of the quadrangle, each supplied with axes, crowbars and scaling ladders. The cavalry was to be stationed in the rear around the fortress to prevent desertion of their own troops and escape of any Texan.

At about ten o’clock at night on March 5 all firing ceased. Travis and other men seemed to have realized that this was the lull before the storm. The Texans worked until midnight strengthening their positions. Three pickets were placed outside the walls to raise the alarm in case of attack; a single sentry stood or walked somewhere within the fortifications. For twelve days and nights there had been almost no surcease to besieger bombardment and to defender vigilance. Now in the quietness the men fell asleep beside rifles and cannons.

Whether the first charge was made at four or five o’clock is debatable. It was announced by a single bugle blast, and then by shouts of rushing Mexicans. The Mexican artillery could no longer fire without danger to its own men.

“Come on, boys, the Mexicans are upon us,” Travis yelled as he ran across the courtyard to a cannon at the northeast corner.

There was evidently enough light from the sky to enable the Texan cannons to rake the assaulting columns. The Mexicans fell by the hundreds. They reeled back twice before making the third rush that carried them to the walls. Here the cannon could not be depressed sufficiently to reach them, but rifle fire on them as they scaled the ladders was deadly. Many fell from blows on the head, knocking down men beneath them. According to one reliable account, out of 830 men in the Toluca battalion, only 130 were left alive. With sabers and pistols, reserves behind the attackers forced them on.

Meanwhile Mexican buglers were blasting out the dreadful notes of “El Deguello”—the call of fire and death that had come down from Moorish Wars in Spain—deguello meaning literally “throat-cutting.’’

Within half an hour of the first assault, Mexicans were pouring over the walls—“pouring over like sheep,” Travis’s slave boy, Joe, who survived, said. In the hand-to-hand fighting, the Texans, unable to reload rifles and pistols, used them as clubs; they cut with knives and swords, grappled bare-handed. Travis was shot through the head beside his cannon. Bonham fell at another cannon. Crockett was still defending the picket stockade when he fell. Bowie died on his cot after he had emptied his pistols into invaders of his room; some claim that in a paroxysm of fury he arose from the cot and killed with his knife.

The last retreat was into the chapel. Here Maj. Robert Evans had seized a torch to pitch into the powder magazine when he was shot down.

According to one Mexican account, five empty-handed Texans tried to surrender and were slaughtered.

It is impossible to be absolute on the number of either Texans or Mexicans killed. There could hardly have been a dozen more than the 187 Texans listed by Amelia Williams, the first scholar on Alamo history. In his official report Santa Anna said that he lost 70 men and killed 600 Texans. His private secretary said that the Mexican dead amounted to 1,544; a Mexican sergeant reported around 2,000. Other reports range between 521 and 1,200. Around 1,500 seems a credible figure.

After the last Texan was killed, Santa Anna asked to be shown the bodies of Travis and Bowie. Then he ordered his cavalry to drag in mesquite wood for burning the bodies of all the Texans. The wood and the dead were piled up layer by layer and fires started.

The dead Mexicans were ostensibly given Christian burials, but the trenches dug in the graveyard were not long or wide or deep enough to hold all the bodies, and many were pitched into the San Antonio River.

Thermopylae had her messenger of defeat. The Alamo had none. None but a woman and a slave who escaped to freedom the next year.

On March 2, the long-awaited Declaration of Texas Independence had been issued at Washington-on-the-Brazos by men elected to form a new government. With full executive powers, General Houston was forming an army to fight Santa Anna even before he heard of the fall of the Alamo.

Two Sundays following the fall, Fannin surrendered to one of Santa Anna’s divisions all his men who had not been cut off and cut down. A week later, on Palm Sunday, March 27, the unarmed prisoners were marched out, formed in lines and shot down by their guards. This was the Goliad Massacre.

Now the inhabitants of Texas were abandoning their homes everywhere and fleeing east in what is called the Runaway Scrape. Santa Anna was extending his lines; Houston was shortening his. On April 21, at San Jacinto on Buffalo Bayou, near what is now the city of Houston, the Texans charged the Mexicans, yelling “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” Their fury was unbounded. With few losses they annihilated Santa Anna’s army. Many a Mexican trying to surrender called out, “Me no Alamo, me no Goliad.”

“Remember the Alamo!” That cry, like the shot fired at Concord, has been heard around the world.

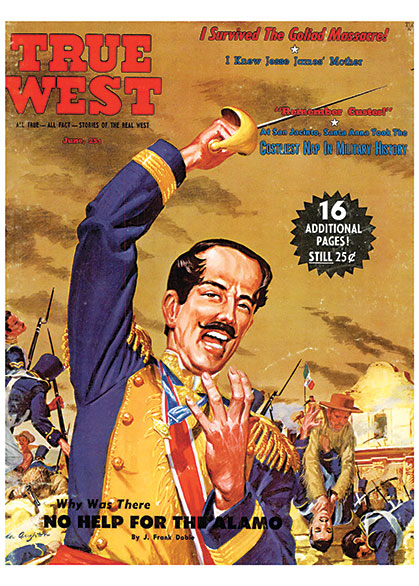

Editor’s Note: Before Texan Joe Small launched True West magazine in 1953, the Austin-based publisher sought counsel and advice from the greatest Texas historian and folklorist, J. Frank Dobie. In honor of that friendship, True West is launching its monthly “Classic True West” department with an abridged version of Dobie’s June 1959 cover story. If you’d like to read the full article, please go to TrueWestMagazine.com and subscribe for full access to 66 years’ worth of exciting issues of True West.