– All images courtesy Brian Lebel’s High Noon –

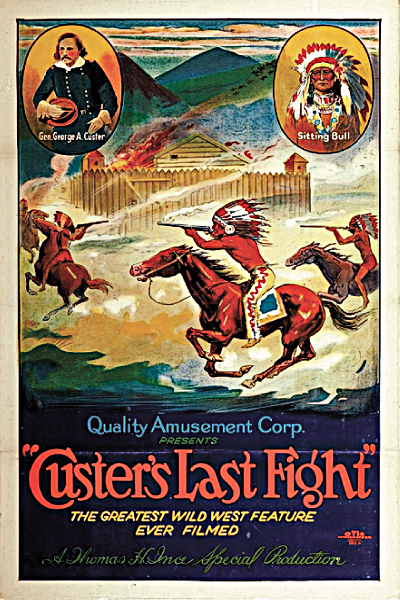

The “first firearm forensically proven to have been used” at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, as the auction catalog noted, hammered down for a quarter of a million dollars at Brian Lebel’s High Noon in Mesa, Arizona, on January 27.

Collectors of artifacts tied to George Custer-—who history best remembers for his decisive defeat in June 1876 that led to the deaths of him and a detachment of 7th Cavalry troops—first widely learned about this Sharps 1874 rifle in a 1988 article written for Man at Arms Magazine by historical archaeologists Douglas D. Scott and Dick Harmon. They discussed not only the supporting forensic evidence, but also the pitfalls of verifying Custer battle guns in general.

An accidental range fire in 1983 paved the path for a 1984 survey of the Montana fight site. Southeast of Lt. James Calhoun’s position and also on Greasy Grass Ridge, archaeologists recovered empty .50-70 caliber cartridge cases, among cases from other firearms, on known Indian warrior positions. The ballistic comparisons of two Martin-primed cartridge cases provided near-certain proof that the 1874 Sharps sold at the auction was fired on Custer’s battlefield.

Further evidence of the rifle’s strong provenance is the unbroken family chain of custody. The rifle, bearing serial C54586, was shipped on April 23, 1875, to Schuyler, Hartley and Graham, one of Sharps’s largest agents who shipped many early rifles west for the buffalo hide hunting trade. It was found on the Little Big Horn battlefield in 1883 by rancher Willis Spear and stayed with the family until it was sold at the auction.

If any doubt could be raised on this being a Custer battle gun, it is the fact that the rifle was not found closer to the battle date. Some could speculate that it was fired in 1883 or even afterward, since access to the battlefield was unrestricted, says C. Lee Noyes, a retired U.S. Customs officer and former editor of the Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association quarterly newsletter.

“And there is at least one known and photographed instance of a military firing demonstration there, in 1886, during the 10th anniversary of the Custer battle. In addition, Capt. Edward S. Luce, a 7th Cavalry veteran and long-time park superintendent, reportedly ‘salted’ the battlefield with cartridge cases and other ‘relics’ for tourists to find,” he adds.

Other Custer battlefield guns before this one, however, had shakier provenance, as they relied solely on historical documentation. As Scott and Harmon wrote, the combination of modern crime laboratory firearms identification procedures with archaeological evidence allowed for this 1874 Sharps to become the “first gun in history that has been scientifically proven to ‘have been there.’”

Collectors who lost out on the chance to bid for a Custer battle gun have another opportunity—at the James D. Julia Auction this April 11-13. A Model 1873 Colt Single Action Army revolver, serial 5773, is one of three that 7th Cavalry Capt. Frederick W. Benteen reported unserviceable after the 1876 battle. This revolver has a “pure Little Big Horn pedigree,” Noyes says.

Collectors earned more than $1.25 million for their Old West artifacts.