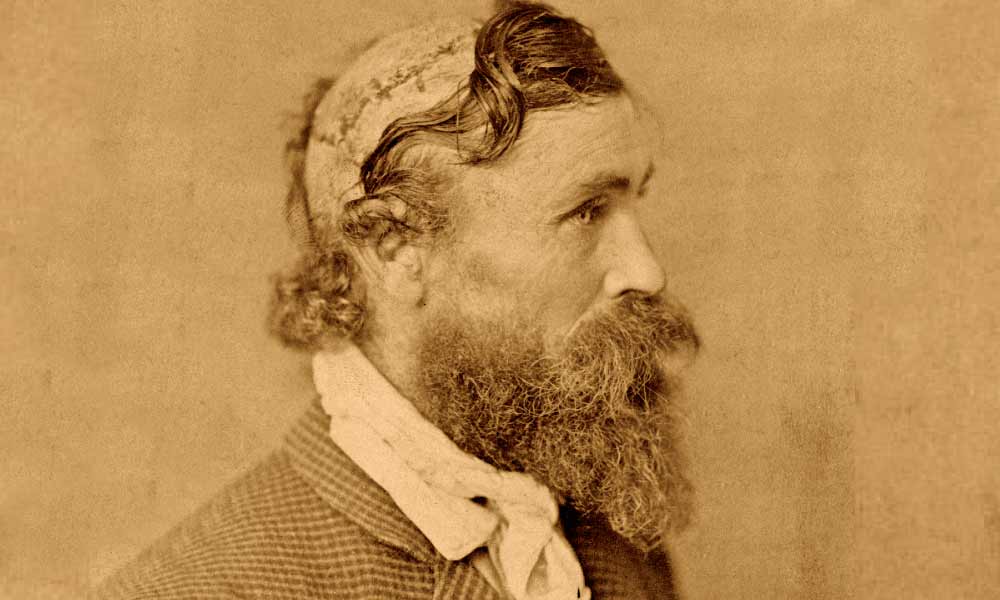

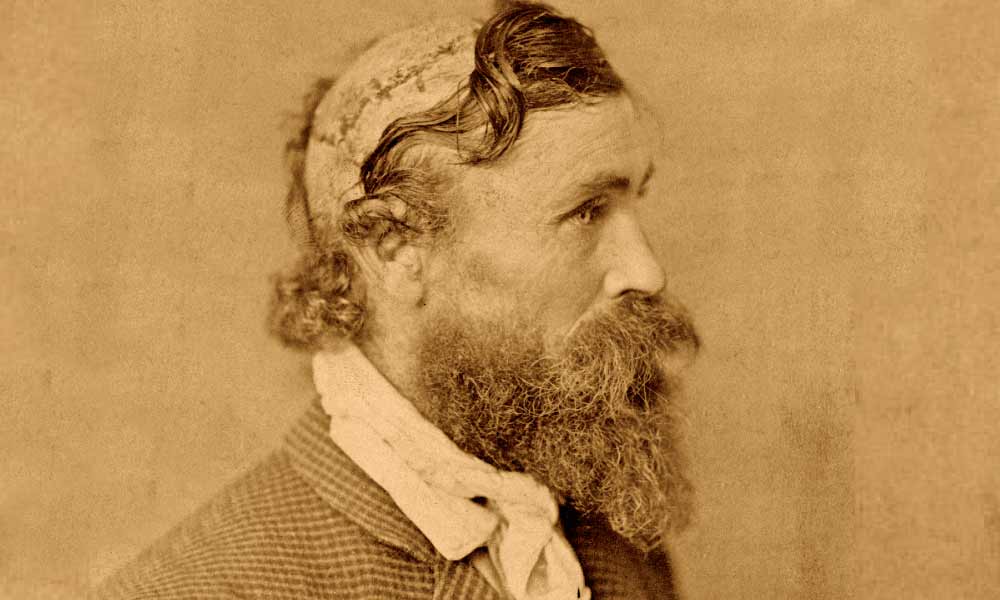

1890 photograph.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

In the summer of 1864, Robert McGee, a tall, slender orphan of 14 years, attempted enlistment at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. He was rejected. Undeterred, McGee signed on as a teamster with H.C. Barret to transport a caravan of flour to Fort Union in New Mexico Territory.

The Barret train started its dangerous journey along the Santa Fe Trail on July 1. Despite several skirmishes with Indians, the wagons traveled roughly 16 miles per day. On July 18, flagging from the heat, the pioneers made camp near Walnut Creek, not far from Fort Zarah near present-day Great Bend, Kansas. With a fort so close, the teamsters and their escort became lax about security.

Shots and war cries from warriors led by Brulé Sioux leader Little Turtle stunned the teamsters. The warriors rode in, shooting arrows and firearms, and mowed down the teamsters within minutes, spattering the grass around the wagons with blood.

The specifics of the fight are confused, being embellished through time to spice up the tale. McGee called his attacker a chief (the chief was Little Thunder, so perhaps Little Turtle was a sub-chief). Some credit other tribes than the Brulé as the assailants: Kiowas, Arapahos or Comanches.

The military watched the slaughter at some distance from the teamsters and apparently made a half-hearted attempt at rescue; the commanding officer was court-martialed. The teamsters had been left to defend themselves with a single firearm and bullwhips. Between eight and 14 of them perished that day.

The Indians dumped the flour on the plains, burned the wagons and stole the mules. Some reports indicated two survived being scalped alive. McGee, however, was the only one who survived long enough to catch public attention.

The events clearly were horrific, but the embellishments made by McGee and the press created a legend rather than a history. Bearing this in mind, McGee claimed he was scalped personally by Little Turtle. While face down in the dirt, McGee suffered multiple arrow wounds, a pistol shot to the back (perhaps by his own pistol) and a tomahawk wound. Many warriors counted coup on him by stabbing him repeatedly with spears and knives. McGee supposedly was conscious when the war leader lifted his patch of scalp an estimated eight inches by 10 inches. As the tale grew in the telling, McGee suffered as many as 18 bullet wounds, although he probably was shot only once or twice.

The burial party was shocked to find the boy alive. “When they undertook to put McGee underground, however, they found a lively corpse, despite the fact that he was scalped and had fourteen wounds, any one of which would have terminated the life of the average man, besides four minor injuries,” The San Francisco Chronicle reported on April 24, 1892.

McGee was taken to the post surgeon who apparently worked a medical miracle to save McGee’s life. Barret, who was absent from the carnage, filed a government claim for damages, a settlement that apparently set him up for life. He abandoned McGee to deal with his disfigurement and recovery alone.

In October 1864, McGee’s case was brought before President Abraham Lincoln, who authorized McGee to draw rations and clothing at any military facility.

While defending the November 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in a speech years later, Col. John M. Chivington further confused the facts by including the “Walnut Creek Massacre” and its 13-year-old scalping survivor among the litany of depredations he felt justified the atrocities of his troops against Indians.

McGee’s story takes on a fantastic aspect in the aftermath, becoming a classic example of printing the legend rather than the truth. His rich uncle supposedly tried to ransom the scalp back from Little Turtle. Newspapers reported a madly insane McGee spending years hunting down Sioux and becoming an Indian scout. The legend depicts the frontiersman cutting notches in his gunstock, each commemorating attainment of vengeance. By 1892, he had taken bloody vengeance on 10 of his tormentors. The largest notch was carved when Little Turtle was “mysteriously wiped out.” With that carving, McGee’s mental health miraculously returned.

The press helped McGee (the “man with 14 lives”) use his disfigurement to establish a career in public appearances. Eminent surgeons experimented on McGee, failing to restore any hair. The legend promoted the fiction that McGee was the only person to ever survive a scalping. Congress introduced a bill to pay McGee as much as $10,000 for his suffering, from Sioux annuities.

In an 1889 visit to Topeka, McGee visited with one of the officers at Walnut Creek, Capt. Oscar F. Dunlap; the Wichita Eagle reported that McGee was sickly and his scalp wound still oozed. The following year, McGee was in “robust health” as seen in a startling photographic image of his wound that was widely reproduced.

By 1893, the “greatest living Indian scout” was appearing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with a “large collection of Indian curiosities” for an admission of 10 cents. Step right up and meet the legend, but consider the young man who, left for dead on the battlefield, rose up and gained celebrity as America’s most famous scalping survivor.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.