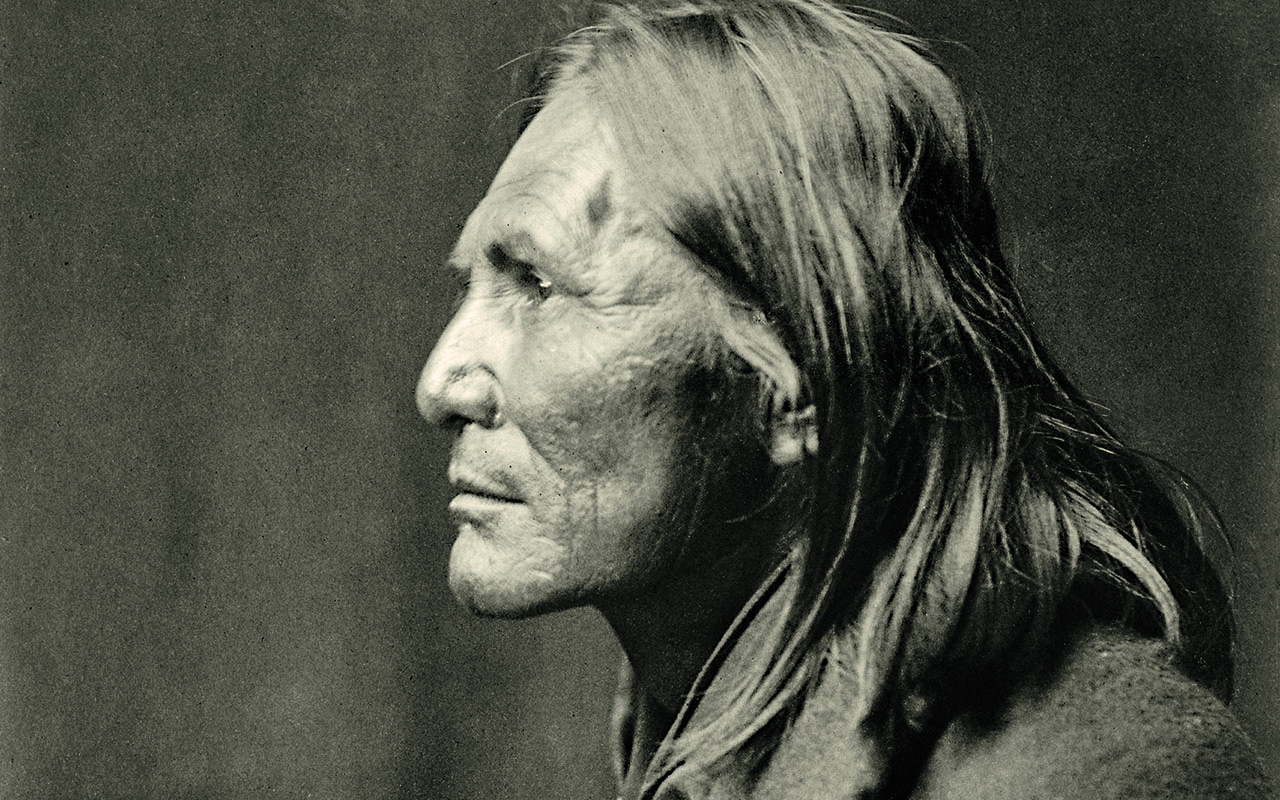

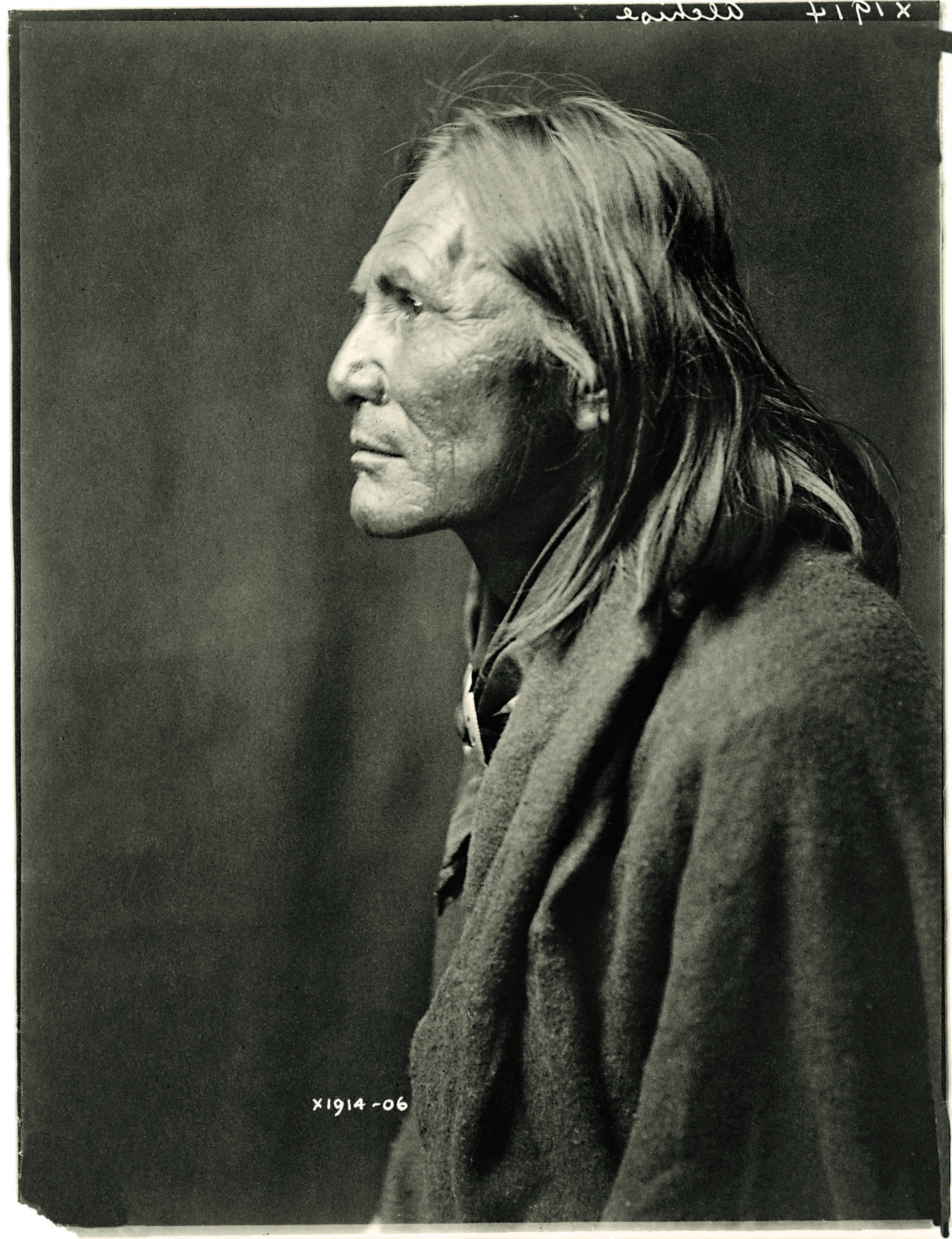

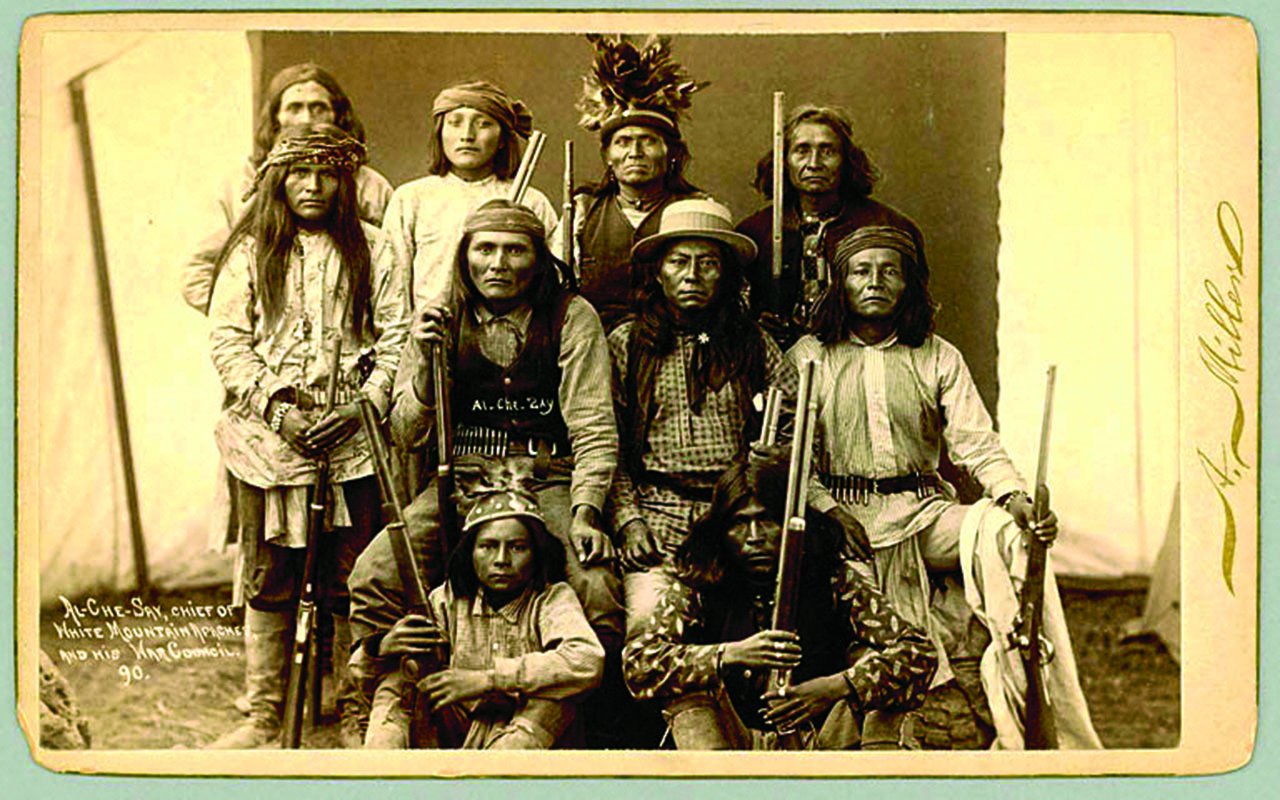

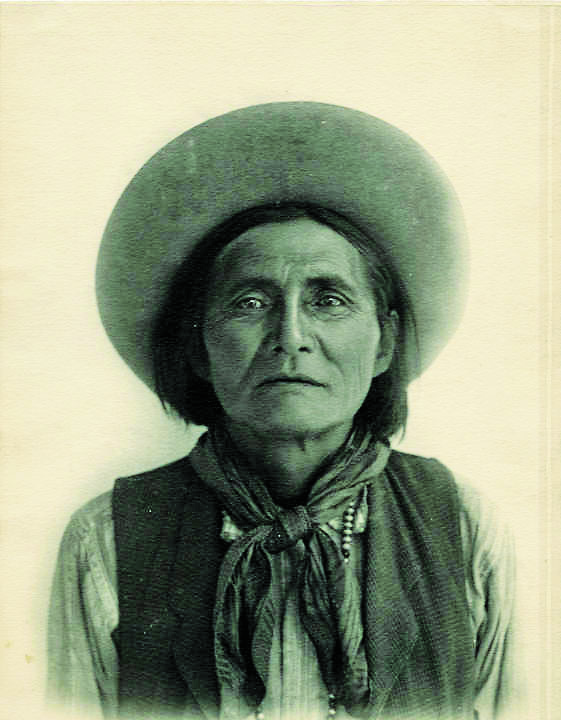

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

“He was “a perfect Adonis in figure, a mass of muscle and sinew, of wonderful courage, great sagacity, and as faithful as an Irish hound.”

—Captain John Bourke, Third U.S. Cavalry

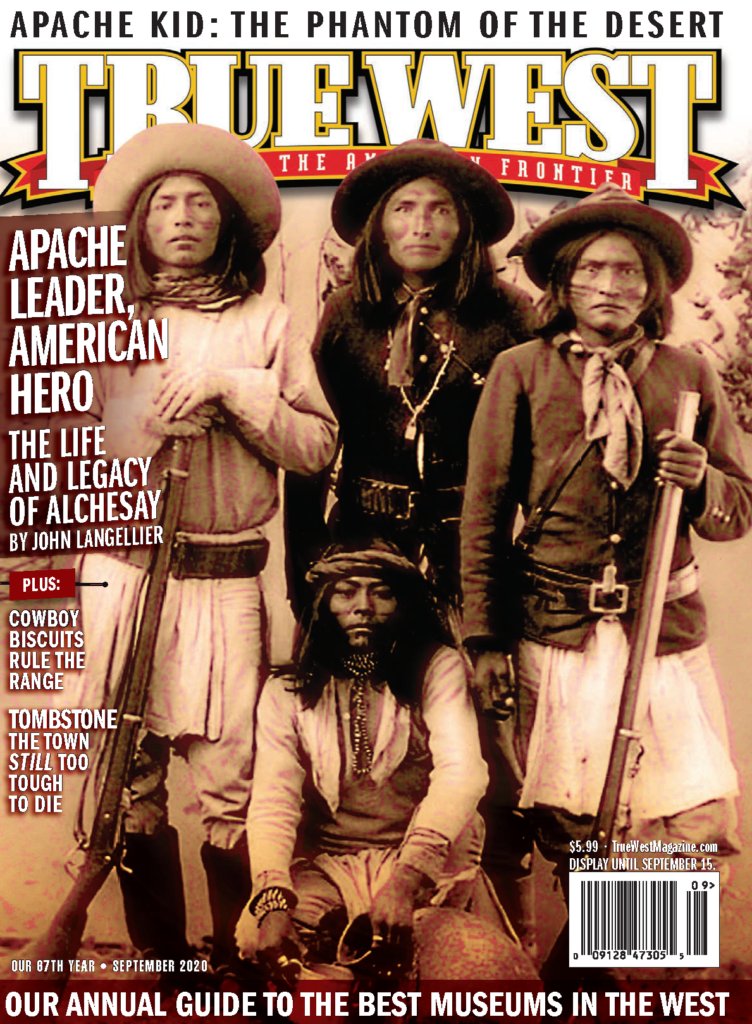

Captain John Bourke, a Medal of Honor recipient for “gallantry in action” during the Civil War Battle of Stones River, Tennessee, recognized a fellow fighting man when he described the Sierra Apache Alchesay, also known by other names including Tsáj (“Swollen One”). And Bourke claimed this impressive young man was a marvel of “physical endurance and manly beauty.”

Related to the venerable Chief Pedro (Eskeh-yan-ilt-klindn, “Angry He Shakes Something”), Alchesay began life around 1850 on the upper north fork of Carrizo Creek in north central Arizona. He grew up among the tac tci dn (red rock strata) clan in the Cibecue Creek Valley near the town of today’s Whiteriver. Little is known of his formative years, but he undoubtedly learned the survival skills of hunting, tracking and warfare. Mastery of this Apache male trinity served him well after 1871, when Lt. Col. George Crook assumed command of the Department of Arizona.

After centuries of conflict, first with the Spaniards, then the Mexicans and, finally, the white American settlers, the Apaches faced a determined enemy in the United States Army. At first, they held their own, but with Crook’s arrival, the tide began to turn.

Crook viewed the Apaches as tenacious “tigers” who could only be brought to bay by unconventional means including the employment of Indian scouts. He maintained that to “polish a diamond” one had to resort to “diamond dust.” For this reason, he soon enlisted 44 Apache men from the White Mountain, Aravaipa and Cibecue bands as key components in his operational plan. These men, he contended, “understand thoroughly what is expected of them, and know best how to do their work…. Their best quality is their individuality.”

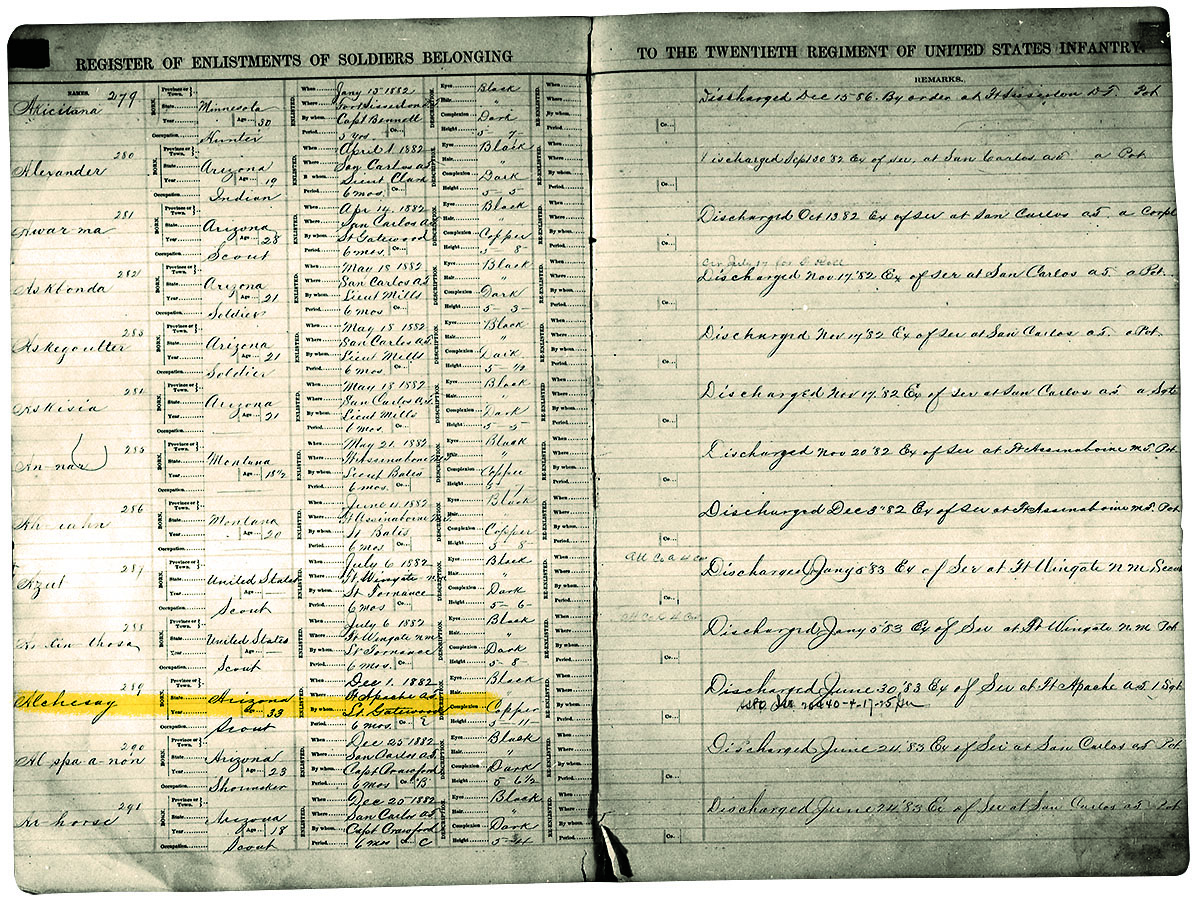

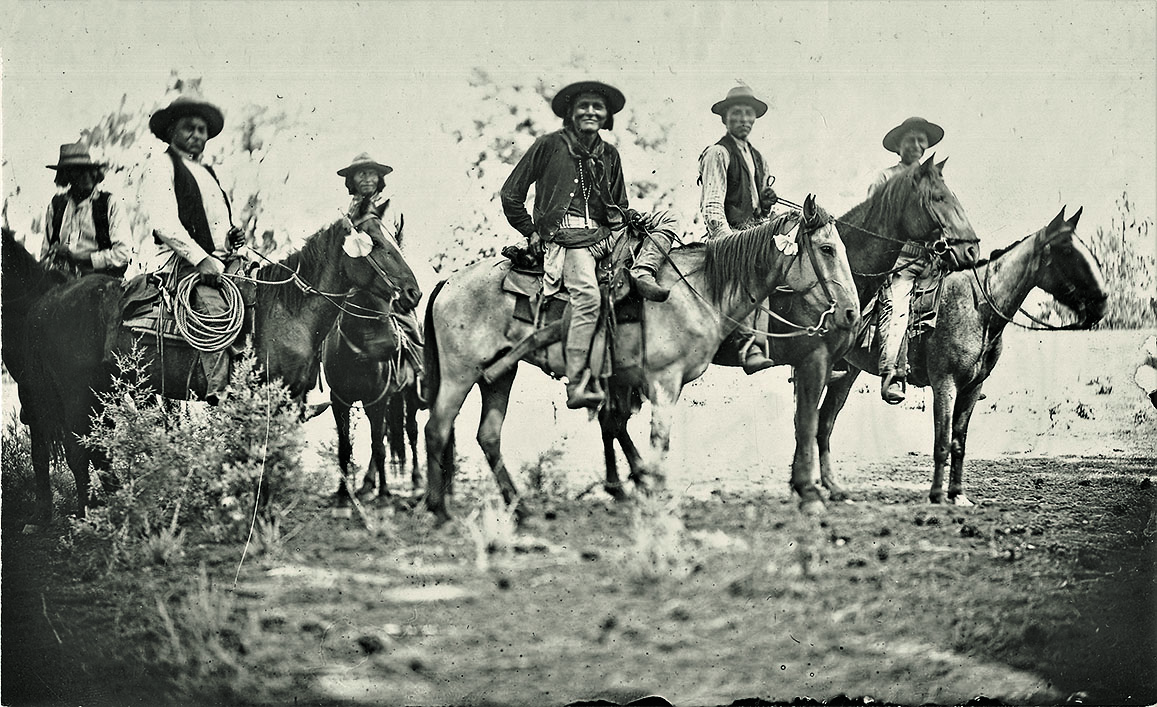

– Courtesy NARA, no. 519781 –

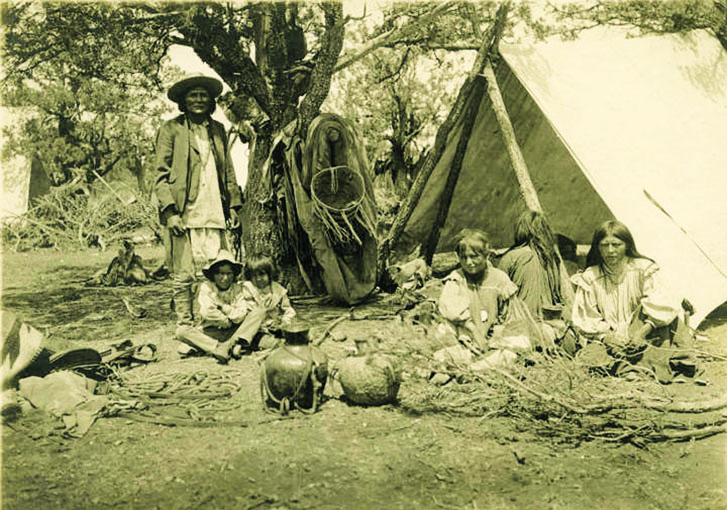

– All photographs courtesy the author’s collection unless otherwise noted –

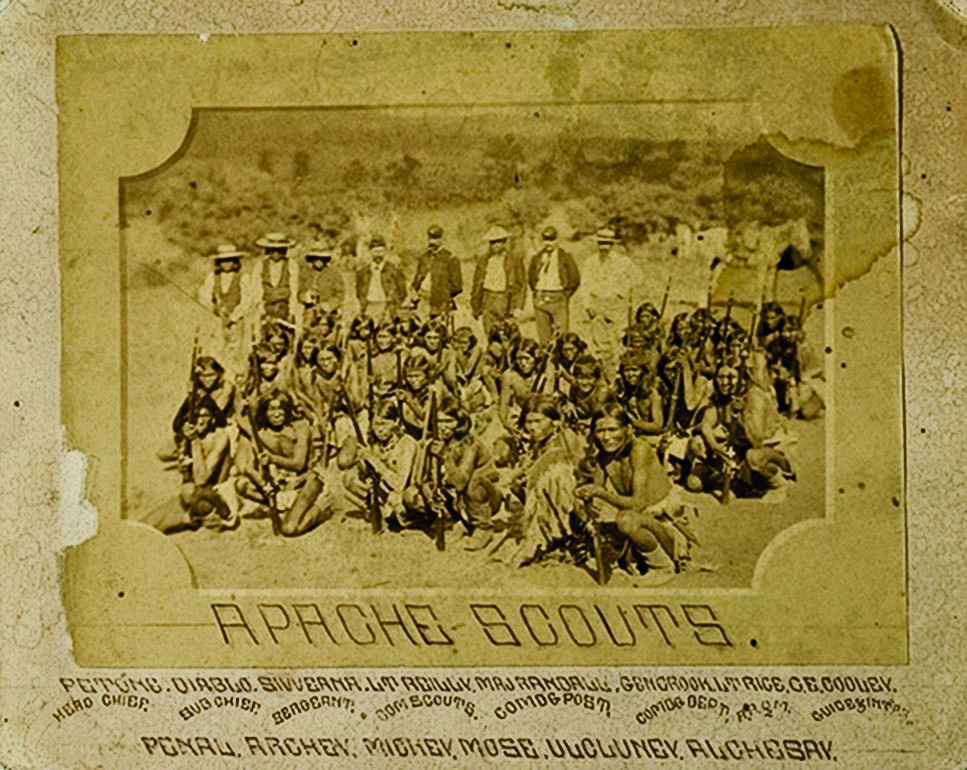

– Courtesy Navajo County Library –

Among these enlistees were Pedro, Miguel, Diablo, Alchesay, Petone, Machol, Blanquet, Chiquito and Noch-ay-del-Klinne, known to the whites as “Bobby Deklinny.” Bobby subsequently left scouting to become a religious healer, his beliefs eventually stirring up unrest that ended in the tragic Battle of Cibecue.

This clash, however, was nearly a half dozen years in the future. For the present, Alchesay and his fellow scouts, commanded by 23rd U.S. Infantry Capt. George M. Randall with civilian scout Corydon Cooley, who was related to Alchesay through marriage, deployed alongside cavalrymen with a vengeance. During the winter of 1872 and 1873, Randall’s strike force combed the countryside.

On March 27, 1873, their efforts produced results. At dawn, horse soldiers and scouts struck an enemy rancheria at Turret Mountain, taking the inhabitants by surprise. A short, sharp exchange ended with many of the villagers dead, some of whom even hurled themselves off the cliff to avoid capture. In fact, only 15 survived to be taken as prisoners.

Just under a month later, on April 25, 1873, Randall’s contingent fell upon another band, one led by Delchay, whom Crook dubbed “The Liar.” After locating Delchay’s camp near the headwaters of Canyon Creek, it took Randall only a few shots to convince the surrounded men, women and children to give up rather than suffer the fate of the unfortunate Turret Mountain group. They reluctantly marched off to Camp Apache.

– Timothy O’Sullivan, Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections –

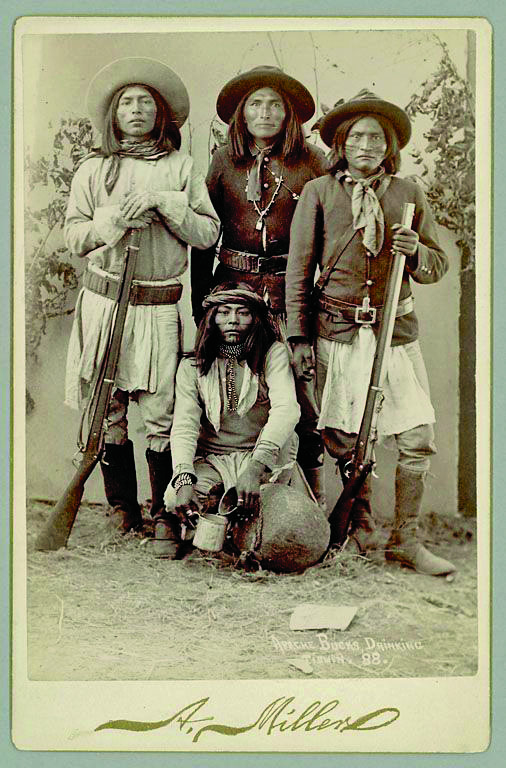

– Courtesy Jeremy Rowe –

Crook enthusiastically wrote his superiors about the role played by the scouts. On June 30, 1873, he sought Medals of Honor for 10 of them. More than two years passed before the War Department responded in the affirmative. Alchesay was among this prestigious cadre, all of whom had been cited for “gallant conduct during the different campaigns against and engagements with the Apaches during the winter of 1872-1873.”

Bravery does not always coincide with perfect conduct, as the actions of Medal of Honor-holder Alchesay attested. A day after his second of many enlistments, the now veteran scout decided he had business elsewhere. He disappeared until September of 1873. Although he was listed as a deserter during his months of absence, Alchesay’s voluntary surrender brought no punitive actions. In line with Crook’s rather paternalistic views, the general recommended “leniency for minor offenses committed by Indians.” Word came from departmental headquarters that Alchesay was to be “restored to duty, without trial, to serve out his enlistment as a private.” This incidence of AWOL did not mar Alchesay’s military prospects because he was appointed to a sergeant even after his unauthorized absence from duty.

Indeed, when under Crook’s 1873 orders that each soul residing on the reservations be assigned an individual tag with a letter and number identifying their band and themselves, Pedro’s people were designated as Band A. Alchesay received tag A1. Clearly, government officials acknowledged his important status at this early stage.

Nevertheless, as with many confined to the reservation, there were peaks and valleys for Alchesay, but he managed to stay relatively aloof of serious problems for several years after he left the scouts. That proved true until 1881, when former fellow scout Noch-ay-del-Klinne shared his vision of a world without whites. He preached the resurrection of Apache dead who, along with the living, would drive out the white invaders. His teachings, somewhat akin to the Ghost Dance at Pine Ridge in 1890-91, a decade later, fomented fears of an outbreak at the San Carlos Agency.

Whether true, or not, Crook’s replacement in Arizona ordered Col. Eugene A. Carr at Fort Apache to send elements of the Sixth U.S. Cavalry with the express purpose of either capturing or killing the prophesizing holy man. Carr obeyed, taking Noch-ay-del-Klinne into custody. This arrest provoked a violent backlash. A number of Apaches attacked Carr’s column as they headed back to the post. During the firefight some of the scouts went over to the Apache side. When the fighting ceased, six of Carr’s men were dead, as was Noch-ay-del-Klinne and an unknown number of his supporters.

Returning to Fort Apache on August 13, 1881, the garrison withstood a brief siege before reinforcements arrived. In the aftermath, the U.S. government reacted by looking for ringleaders related to the outbreak and actions that took place in its wake. This resulted in Alchesay’s arrest, and the execution of three scouts, along with the imprisonment of a few others—a state of affairs which lasted for several months. Finally, the October 24, 1882 edition of Tucson’s Arizona Star reported the findings of a federal grand jury condemning conditions at San Carlos and the treatment of Alchesay and 10 of his fellow prisoners “who were held in confinement” by the Indian agent “for a period of fourteen months without even presenting a charge against them.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Their release followed. Alchesay was back on the reservation after George Crook, now a brigadier general, again held the reins of the Department of Arizona.

Making his fact-finding rounds, Crook included Fort Apache, where he conferred with Alchesay and scores of others. The one-time scout and Pedro both questioned why military authority on the reservation had given way to civilians from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This change eventually ignited a powder keg of distrust and violence because of the supposed mismanagement and duplicity of the Indian agents and their cavalier approach to whites encroaching on the reservation.

Airing his grievances along with those of many gathered there, Alchesay was content to again throw in his lot with Crook and the Army. In 1883, when the general headed into the wilds of the Sierra Madre in Mexico, Alchesay rode with the punitive expedition seeking Chirachua Apaches accused of constant raids on both sides of the border. Again, John Bourke noted Alchesay among those Indians who were “all tried and true men, experienced in warfare and devoted to the General whose standard they followed…”.

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

Once more, in 1885, Alchesay joined Crook for his foray against Geronimo. After months of rugged campaigning, Geronimo agreed to meet with Crook. By March 22, 1885, the general dispatched Alchesay and a handful of scouts in advance to the designated meeting place, where after his arrival he assigned another mission. Alchesay and Ka-en-ten-na, a onetime so-called “bronco” Apache who had opposed Crook in 1883, to “make talk” with several of the prominent men among the Chiricahuas. They were to speak for peace and abandonment of Geronimo if he persisted in fighting.

The next day, Crook met with these headmen along with Geronimo. One of them, Chief Chihuahua, concluded his long diatribe with the words: “I think a great deal of Alchise and Ka-en-ten-na; they think a great deal of me.” Then he expressed a wish that they could end the war and exist as friends and in brotherhood.

In due course, Geronimo had his say to Crook, ending with “I surrender myself to you…. I want now to let Alchisay and Ka-en-ten-na to speak a few words.” The latter spokesperson indicated that Alchesay would represent both of them,which he did succinctly. He urged Crook to hold no “bad feelings” toward his former foes. He indicated that they all wanted the general “to be in charge of us and no one else, you know me well; I have never told a lie, nor have you ever told me a lie, and now I tell you that these Chiricahua really want to do what is right and live at peace.”

Regrettably, while Alchesay’s words rang true, Geronimo and a small number of holdouts reneged on the desire to halt hostilities. They bolt-ed, most probably to Alchesay’s chagrin. He had pledged his honor on their behalf; something he took most seriously. Not until September 1886 did the bloodshed end after a conference with Geronimo at Skelton Canyon.

Having served faithfully, Alchesay left the scouts. He took up ranching near the north fork of the White River. During the decades that followed, he made several trips to Washington, DC, to meet with presidents and other officials as a champion for the rights of his people. He also advocated education and he converted to Christianity. In the process, he developed a staunch friendship with the Reverend Edgar Gunther and his family at the nearby Lutheran mission.

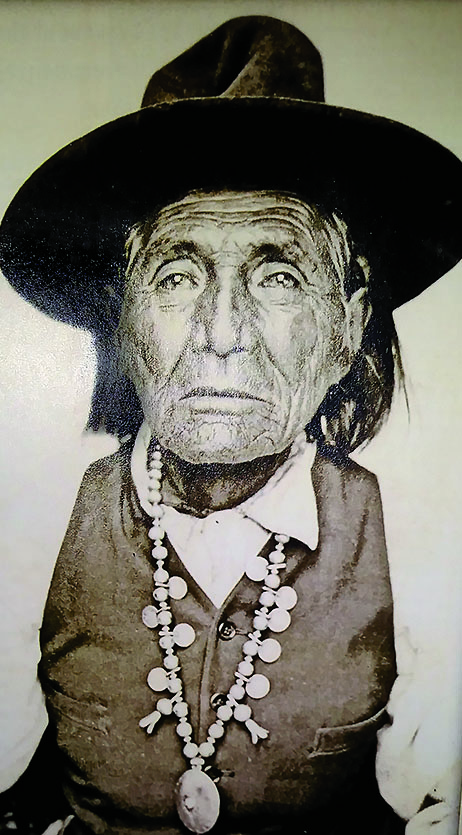

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– Courtesy Jeremy Rowe –

Toward the end of Alchesay’s remarkable existence of nearly eight decades, the Holbrook News for October 20, 1922 observed: “Alchesay is an old man and has seen great changes during his life time.” The article added: “He is a man of remarkable character and it is seldom you find one who can speak with equal sententiousness, be the[y] white or red. Asked once years ago what he thought of the rough country around Fort Apache, he said: ‘Well. God made the country, so it’s all right but if the white man had made it, we would never have forgiven him.’”

Alchesay died on August 6, 1928. A headstone in the White River Cemetery on the Fort Apache Reservation bearing the image of a Medal of Honor marks the grave of this remarkable role model. Arguably, the more fitting tribute than the one attesting to his valor, is the high school that bears his name. His passion for education, untiring efforts to benefit his people and willingness to adapt bespeak an extraordinary man for all seasons.

John Langellier’s numerous publications include American Indians in the U.S. Army Forces, 1866-1945.