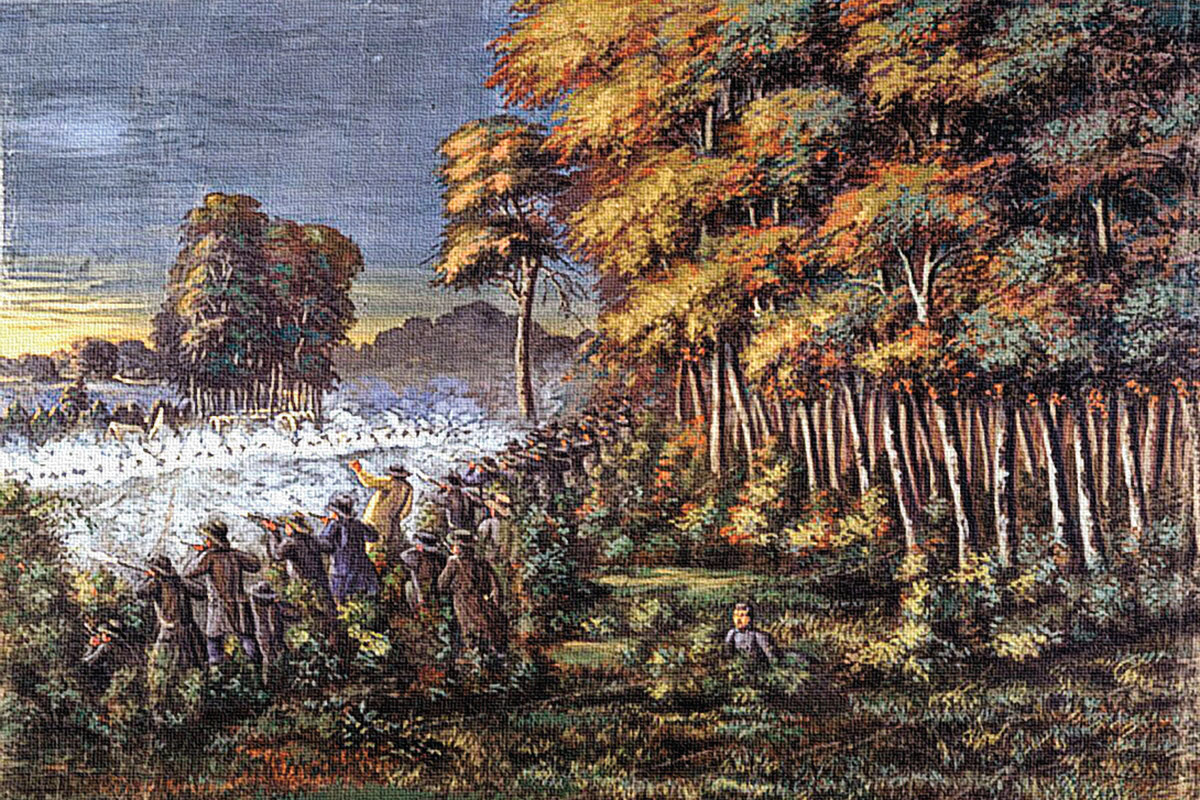

— Painting by C.C.A. Christensen, True West Archives —

In 1831, the Lord supposedly spoke to Latter-Day Saints prophet Joseph Smith. The Mormons were based in Kirtland, Ohio, but the situation was tense. Non-Mormons—“Gentiles,” according to the LDS—didn’t like them, and persecution was common. So the prophet was told to move west, to the New Jerusalem. Most folks called that place Independence, Missouri. And if things had been bad in Ohio, they were disastrous in the Show Me State. Especially when the Mormon War erupted seven years later.

Thousands of Saints, mostly from the Northeast as well as Ohio, flooded into the five western counties of Missouri. They and the church began buying up dozens of sections of land in an effort to build their promised land. That made local residents nervous. There were other factors at play as well. Most of the Mormons were abolitionists, not a popular stance in a pro-slavery region.

The LDS were also dismissive of the Gentiles. The proposed New Jerusalem didn’t want outsiders to even visit, let alone settle there. Those who already lived there would be forced out. But on the other side of the coin, the Mormons reached out to Indians, who were still attacking some whites on the Missouri frontier.

The New Jerusalem was never built, and the Mormon base was at Far West, about 55 miles north of Kansas City. From there, the faithful branched out through northwest Missouri. By 1838, they were a major political, social and economic force. The election on August 6, 1838, brought things into the open. Thirty Mormons showed up to vote in Gallatin; they were refused and a brawl broke out. Mormons drove off their attackers, but it was just the first skirmish in the so-called Mormon War.

Organized mobs forced saints to leave Caroll, Livingston and DeWitt counties, virtually clearing DeWitt of Mormon settlers. Some women and children died in the exodus, exacerbating the bad feelings. Mormon militia attacked Gentile homes and nearly burned Gallatin to the ground. By October, each side asked Gov. Lilburn Boggs to intervene; he refused, saying it was a local matter.

Some Mormon leaders became alarmed. Two of their apostles left the church over the attack on Gallatin. But even that didn’t slow things.

The two sides met in pitched battle on October 24 at Crooked River in Ray County. Three Mormons and one militiaman were killed before the militia broke and ran. Reports from the battlefield were exaggerated, but Governor Boggs was finally moved to action. On October 27, he issued Order 44: “The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description.”

Two days later, a vigilante band took those words to heart. They attacked an LDS settlement at Haun’s Mill. Seventeen Mormons were killed, some while trying to surrender.

A major force of militia then surrounded the church headquarters at Far West, trapping Joseph Smith and other LDS leaders. They were to be tried for treason, but jailers allowed Smith to escape and the others were released in order to cool the situation. The Mormons were forced to give up their lands and personal property. Led by Smith, they relocated to western Illinois, to a place they called Nauvoo. The Mormon War was over. Mostly.

In 1842, Governor Lilburn Boggs was shot and wounded in his home by an unknown assailant. Many believe the shooter was Porter Rockwell, bodyguard of Joseph Smith, and his successor Brigham Young. That may have been the last shot of the Mormon War.