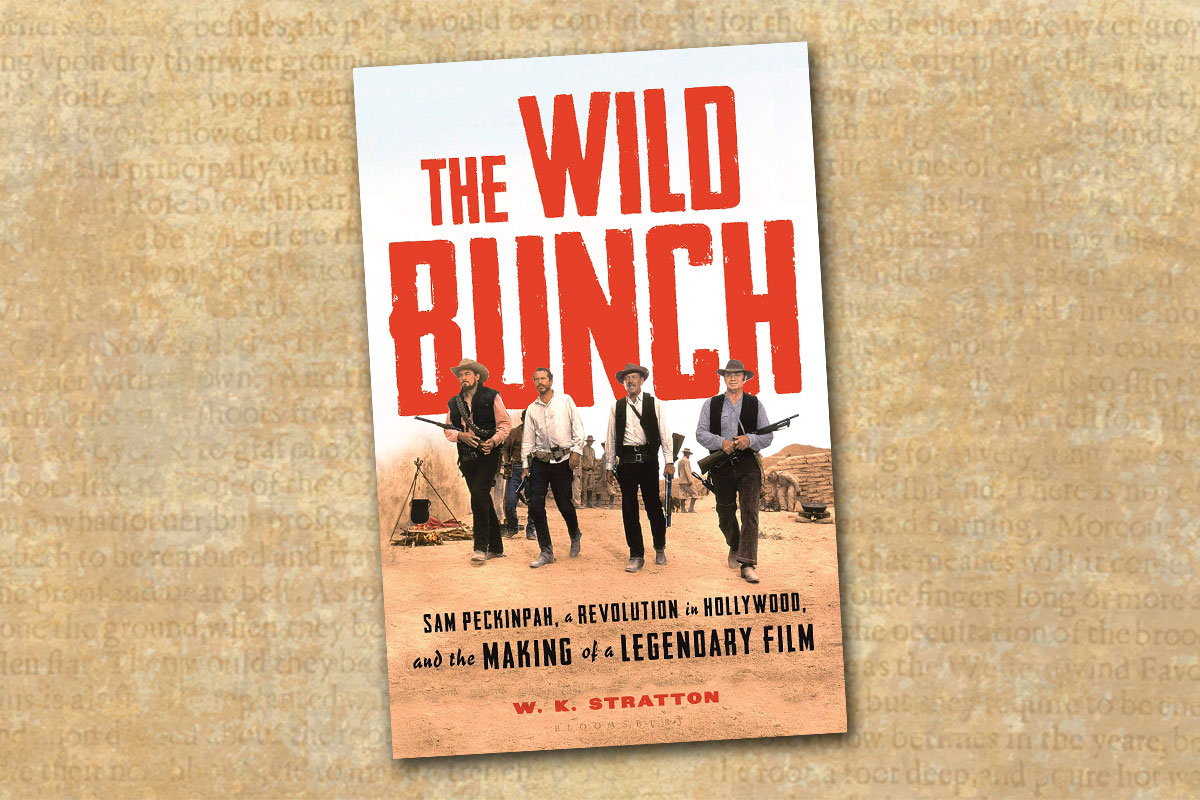

In June 1969, director Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch was released in theaters across the United States to critical acclaim and vitriol. Film critics equally loved it and hated it with as much vehemence and polarization as their contemporaries opining in American newspapers and networks about the Vietnam War. Five decades later, W. K. “Kip” Stratton’s The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood and the Making of a Legendary Film (Bloomsbury, $28) sets the record straight on the controversial classic, now considered one of the greatest films, let alone Westerns, of all time. “The Wild Bunch’s bloodletting has been trumped many times during the past fifty years, yet the psychological impact of the film’s violence has not diminished. …It has become a classic film, not just in America but world-wide,” Stratton writes. “Above all else, it was the product of the intellect, the creative sensibilities, and the heart of its director, Sam Peckinpah.”

In recent years, the Western filmmaker biography has become a popular category. Just last year, John Farkis’s The Making of Tombstone: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Modern Western and the memoir Junior Bonner: The Making of a Classic with Steve McQueen and Sam Peckinpah in the Summer of 1971 by my father, Jeb Rosebook, put cinema fans on the set and behind the scenes from concept to distribution of the two Westerns. Stratton followed this model brilliantly in The Wild Bunch, with a fresh biography of Peckinpah, an in-depth review of the creative writing process of the script and a blow-by-blow recounting of the pre-production, production, post-production and release of the film. As the son of a screenwriter, I especially appreciated Stratton’s attention to the creative process behind the writing of the script. As screenwriter Walon Green reflected, “I wrote it, thinking that I would like to see a Western that was as mean and ugly and brutal as the times, and the only nobility in men was their dedication to each other.”

Stratton’s dual passion for his subjects, Peckinpah and his greatest cinematic triumph, The Wild Bunch, is enthusiastically and unapologetically summarized in his conclusion.

“It is a Western, in most ways, the last Western. Peckinpah destroyed all the standard stereotypes that made up cowboy pictures that came before it,” Stratton writes. “Peckinpah’s West was a dirty, often vile place, very much like how the Old West was. When The Wild Bunch was released, it placed a tombstone on the head of the grave of the old-fashioned John Wayne Western. It changed all the rules.”

Like Stratton, I am an admirer of Peckinpah and The Wild Bunch. As a boy I met the director. I’ve never forgotten our conversation, which was simultaneously intense

and kind. And maybe it was that burning intensity raging creatively inside Sam Peckinpah, that was bared open with a Biblical vengeance in The Wild Bunch, never experienced in cinema—before or since—that makes it equally the most controversial and the greatest film of all time.

—Stuart Rosebrook

A Renaissance Scout

In White Hat: The Military Career of Captain William Philo Clark (University of Oklahoma Press, $29.95), historian Mark J. Nelson tells the story of the officer many considered the Army’s “Renaissance Man.” Whether or not Clark deserved such praise is up to the reader, but he certainly became involved in major events of the Plains Indian wars, including the surrender and murder of Crazy Horse, Gen. George Crook’s “starvation march” and Sitting Bull’s final fight. His study of Indian sign language remains a classic. He negotiated surrender and peace agreements with the principal chiefs and was a strong proponent of using Indian scouts. That is a lot to pack into a short 39 years.

—Blaine P. Lamb, author of The Extraordinary Life of Charles Pomeroy Stone

Esteban the Great

Drawn from a broad spectrum of secondary sources, Dennis Herrick’s Esteban: The African Slave Who Explored America (University of New Mexico Press, $39.95) takes a new approach to understanding the importance of Esteban. His masters obscured and distorted his history and contributions because he was a slave. He was the indispensable man, a healer and ambassador, in Cabeza de Vaca’s 16th-century journey from Florida to Sonora. The Zuñi may not have killed him. The author suggests that Esteban, having been free and an equal partner with his companions during the journey and having been independent en route to Zuñi, chose not to return to slavery. The stories of his death conflict with each other. Clearly, he was a hero and not a villain.

—Doug Hocking, author of The Black Legend: George Bascom, Cochise, and the Start of the Apache Wars

Recollections of a Western Pioneer

Historian John Hart’s skilled research, attention to detail, and straightforward prose in Bluecoat and Pioneer: The Recollections of John Benton Hart, 1864–1868 (University of Oklahoma Press, $32.95) come together not only to frame his great grandfather’s vivid memories, but to introduce us to new threads weaving through the vast tapestry of frontier history. John Benton Hart fought with the 11th Kansas Cavalry in 1864 Missouri, joined in Wyoming’s Battle of Platte Bridge a year later and rode with Wells Fargo on the Bozeman trail. His colorful anecdotes and key observations, set to paper in the early 20th century by his son, Harry, keep the reader spellbound and help fill the gaps in separate, similar narratives.

—Richard Prosch, author of The Scalper

The Fateful Life of an Outlaw

Johnny D. Boggs’ stories can take you for a ride. His novel Hard Way Out of Hell: The Confessions of Cole Younger (Blackstone Publishing, $16.95) reads like a historical biography and is based on what is known of the outlaw. While the actions of Cole and his outlaw friends are often heartless—killing many who are innocent bystanders—his story is that of an educated, God-fearing man. Readers will discover a Cole Younger who wanted to live a decent and fair life, until war and hard times led him down a road that became difficult, and then eventually futile, to avoid.

—Rex Rideout, singer-songwriter with Mark Lee Gardner of Frontier Favorites: Old-Time Music of the Wild West