Army engineers bent on establishing a wagon route across Montana and into the Pacific Northwest began surveys and explorations in 1853 for what would become the Mullan Road under the direction of Isaac Stevens, a West Point graduate and the first appointed governor of Washington Territory.

Army engineers bent on establishing a wagon route across Montana and into the Pacific Northwest began surveys and explorations in 1853 for what would become the Mullan Road under the direction of Isaac Stevens, a West Point graduate and the first appointed governor of Washington Territory.

That spring, Stevens organized and led an expedition of engineers and explorers west from St. Paul, Minnesota. Their task: to detail the geographical character of the country. Ultimately, they would chart a road to link Fort Benton, Montana Territory, with Fort Walla Walla in Washington.

Serving in Stevens’ first exploratory party was John Mullan, another West Point graduate who was eager to test his engineering skills. They began the survey at Fort Benton and by late fall, they had pushed west to Hell’s Gate, which would become Missoula, where they faced the daunting task of finding a passage through the Bitterroot Mountains.

Mullan, reporting on the situation, wrote: “The lateness of the season, the difficulty of the country, the importance of our mission, the scarcity of our supplies, the meagerness of the information we then possessed and the necessity felt for a more detailed and thorough exploration of the Rocky Mountain section … all conspired to influence Governor Stevens to leave in the mountains a small party for the winter of 1853.”

Stevens assigned Mullan to command the winter party that would select a “suitable location” near the mouth of Willow Creek, build “rude huts” and make “it a centre from which to explore the mountain region.” The site became known as Cantonment Stevens, according to an account by Missoula pioneer Frank H. Woody in his Reminiscences of the Early Days of Missoula County.

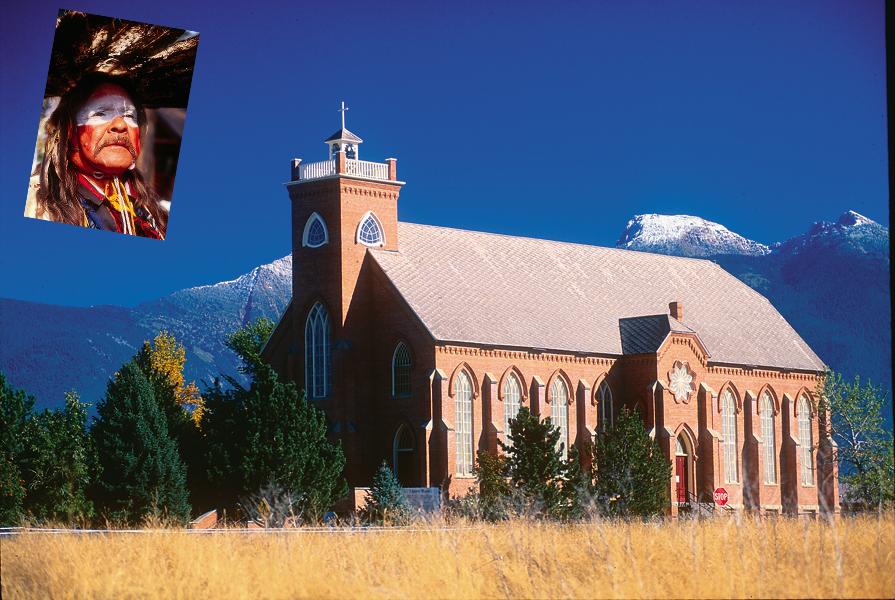

That winter, Mullan and his companions scouted the valley and nearby mountains. One of the enlisted men, Gustavus Sohon, learned the language of the Flatheads and Pend d’Oreilles, establishing himself as the party’s interpreter and earning the confidence of the natives. They provided information for Mullan as he explored north into the Mission Valley with its St. Ignatius Mission and the Bitterroot Valley, where St. Mary’s Mission and Fort Owen would evolve.

Although the army mission was to cut a road, both Mullan and Stevens were well aware that the route would also serve a northern Pacific railway. By 1854, Mullan had determined that the route over Lolo Pass and along the Lochsa River was “thoroughly and utterly impracticable for a railway. The country is one immense bed of rugged, difficult, pine-clad mountains that can never be converted to any purpose for the use of men … In all my explorations I have never seen more uninviting beds of mountains.”

Mullan alternately explored routes farther north including one along the Clark Fork River Valley through Plains and Thompson Falls, a well-established Nez Perce trail, and a route from the Cataldo Catholic Mission in the Coeur d’Alenes to Hell’s Gate. Eventually he settled on the latter route as the most practical. He submitted his report to Stevens, who forwarded it on to the War Department where it languished for two years. During that period, Stevens engaged in treaty talks with Columbia Basin tribes.

Stevens and Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer reached the council grounds May 21, 1855. The Walla Walla, Cayuse, Yakima, Palouse, Umatilla, Spokane and Nez Perce tribes had representatives on hand for the three-week-long council session. The tribal representatives listened as Stevens outlined plans for three reservations to serve the Columbia Basin tribes. His real goal: to push the Indians out of the way for the eventual development of a road for commerce and later construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

The treaty set aside specific lands for the Indians, but miners and other settlers soon pushed into the region, violating the 1855 agreement even before it was ratified. This caused the tribes to stand up for their rights and led to several violent encounters with miners, settlers and eventually the military.

The New York Journal of Commerce reported on March 31, 1858: “The Secretary of War (John B. Floyd) has issued orders to Lt. John Mullan, U.S.A., to proceed immediately to the Columbia River and organize a force to commence at once the work of opening a wagon road from Fort Walla Walla on the Columbia River, to Fort Benton, on the Missouri. The intention of the preliminary is to demonstrate the perfect feasibility of the route, and to open a summer trail for emigrants.”

The paper continued, “Lieut. Mullan is well and favorably known to the public as having been connected with Gov. Stevens’ great survey for the Northern Pacific Railroad, during which he discovered the celebrated pass through the Rocky Mountains, between the head waters of the Prickly Pear Creek on the east and the little Blackfoot river on the west, known as Mullan’s Pass.”

Although Mullan intended to begin the work in 1858, unrest among the Columbia Basin Indian tribes delayed the work. The military launched a force against the tribes in the fall, resulting in the hanging of some tribal leaders and the killing of 800 head of horses. Mullan returned to Congress during the winter, obtained a further appropriation for the work and, in the spring of 1859, had a pledge of $100,000 to commence building the road. Over the next three years, he linked Fort Walla Walla in Washington Territory with Fort Benton, Montana Territory.

Clash in Eastern Washington

To travel the basic route of Mullan’s Road today, take U.S. 12 east from Walla Walla, Washington, to Clarkston and then U.S. 195 north to Rosalia and Spokane. From there, follow Interstate 90 east through Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, to Missoula, Montana. Then continue east on Montana Highway 200 to Great Falls and follow U.S. 87 northeast to Fort Benton.

The rolling country of eastern Washington provided no major obstacles for Mullan’s road-building crew. North of Clarkston, near Rosalia on U.S. Highway 195, you can see a monument to the battleground where Col. E.J. Steptoe, on May 17, 1859, engaged in a fight with Spokane, Palouse and Coeur d’Alene tribesmen as Steptoe and a large military party traveled with Nez Perce guides toward Colville. “[A] number of chiefs rode up to talk with me, and inquired what were our motives to this intrusion upon them. I answered that we were passing on to Colville, and had no hostile intentions,” Steptoe later reported.

The Indians, including Coeur d’Alene Chief Vincent, questioned Steptoe’s motives: “If you are going to Colville on a peaceful mission, why do you have so many men all carrying rifles, with a fully loaded pack train, and with large guns? Why didn’t you go straight to Colville instead of coming around this way?”

When Steptoe did not answer to the tribes’ satisfaction, the Indians attacked, killed several soldiers, and forced Steptoe to withdraw to Fort Walla Walla. This battle and other difficulties delayed Mullan’s road-building enterprise that year. A monument to those who fell in the Steptoe battle is located in Rosalia.

Spokane today is a vibrant, bustling city with an intriguing downtown park where you will find plenty to occupy you—from shows at the IMAX Theater to nearby shopping and dining to rides on the 1909 carousel. To learn more about the history of the fur trade in the Northwest, visit the Spokane House Interpretive Center, which is located near the 1810 site of the North West Company Trading Post.

Blazing a Tree

While traveling east out of Spokane and Coeur d’Alene on I-90, plan to divert off the interstate eight miles east of Coeur d’Alene to Fourth of July Canyon where Mullan’s road-building crew celebrated Independence Day in 1861 by blazing a tree “MR July 4, 1861” and breaking out supplies such as “molasses, ham, whiskey, flour and pickles.” You may walk one of the pathways carved out of the forest by Mullan and his road builders, and see a plaque dedicated in 1878 when the 624-mile Mullan Road was declared a National Historic Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers. This is a great place to take a break from driving and walk through the woods before resuming your journey.

Cataldo Mission in Old Mission State Park in Cataldo, Idaho, is farther east on I-90. The Cataldo Mission is the oldest structure in the State of Idaho, built in 1853 by Jesuit Missionaries. At this site, you may see the craftsmanship of the Jesuit missionaries and learn more about their work with the Indians in the region. Father Anthony Ravelli spent time here as did Father Joseph M. Cataldo, superior of all the Rocky Mountain Missions, who made this his headquarters.

Mullan’s crews “from the 16th of August to the 4th of December, 1859, [cut] through this densely timbered section of 100 miles, building small bridges where required, grading in thousands of places (including) … an ascent of one and three-fourths miles, to the summit of the (Bitterroot) Mountains.”

Road Building Through Montana

Mullan spent more than one winter in the region of “Hell’s Gate,” which eventually became Missoula, Montana. Once east of Hell’s Gate, the road building became slightly easier if only because workers didn’t have to hack a road out of a forest. Montana Highway 200 skirts around the south edge of the Flathead National Forest and then turns northeast toward the open prairie country around Great Falls and Fort Benton.

This is country the Western artist Charlie Russell came to know and love, and you may visit his studio in Great Falls, which is not far from the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center.

Fort Benton, constructed in 1849 as a fur trading post and still a vibrant community, was the uppermost point on the Missouri River served by steamboat traffic in the 19th century. The first steamboat, The Chippewa, in 1859, got as far as Fort Mackenzie (the Marias River) before grounding to a halt and unloading cargo bound for Fort Benton. The Key West, in 1860, did make it to Fort Benton along with The Chippewa. Both boats carried a cargo of soldiers and some freight; most of the other freight had been offloaded at Fort Union.

Fort Benton is a quiet river town where you may visit the Museum of the Northern Great Plains, Montana’s agricultural museum, and the Museum of the Upper Missouri, or find a meal or place to stay at the Grand Union Hotel.

Work on the initial road construction and subsequent improve-ments continued until 1861. It had cost $230,000, but Mullan estimated it would take another three-quarters of a million dollars to put the road into the shape he envisioned.

Lieutenant James E. Bradley, who served under Mullan, later said the road construction involved 120 miles of difficult timber cutting, plus another 400 miles of open timbered country and rolling prairie. The crews had built hundreds of bridges and several ferries to serve the expected traffic.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Donnie Sexton / Travel Montana unless otherwise noted –

– By Candy Moulton –