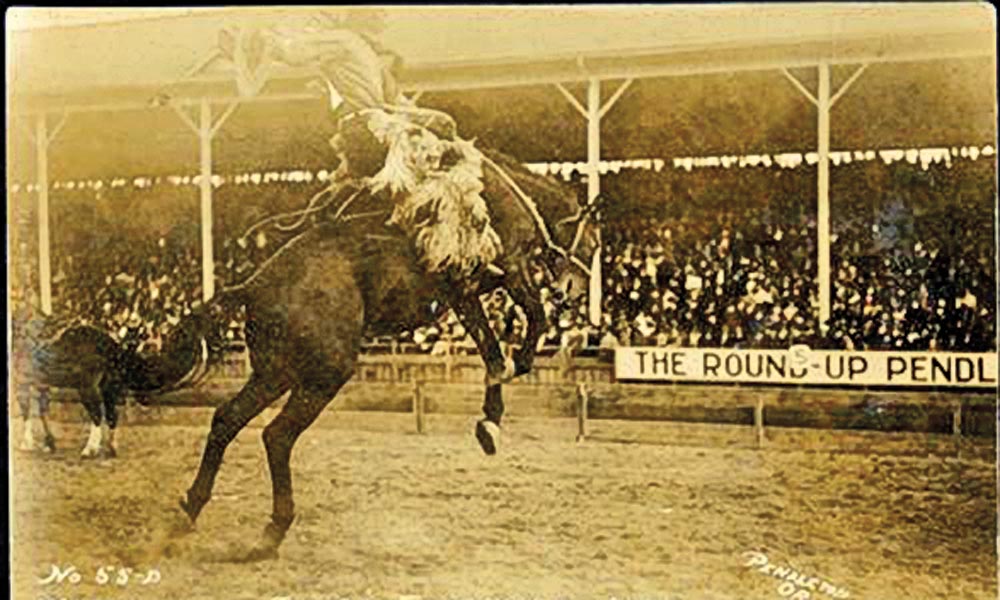

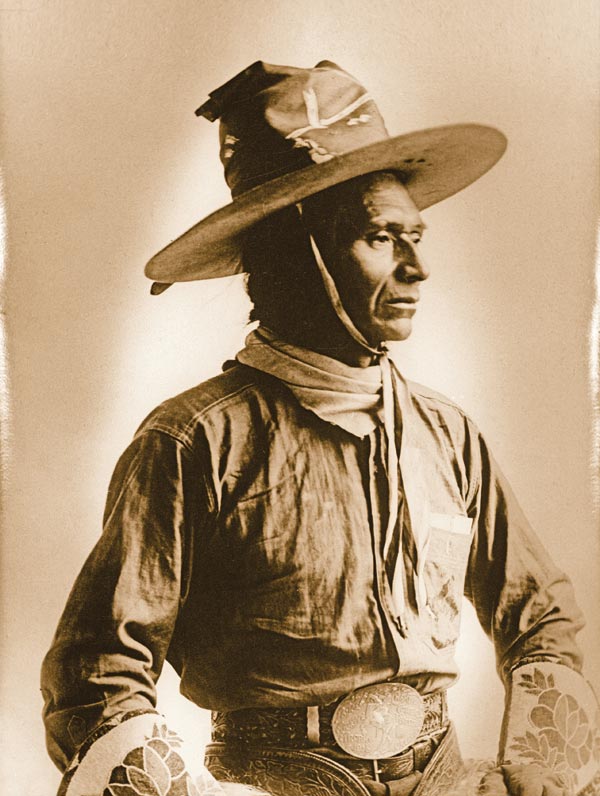

– all images Courtesy Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum / above: Don Bell Collection, 2001.032.003 –

Stereotypical pairings often plague the American West. Outlaws and lawmen. War bonnets and Winchesters. Cattle drives and wagon trains. None, however, is more engrained than cowboys and Indians. For decades, these adversaries have dueled on the pages of books, the screens of cinema and television, and in backyards and schoolyards across the U.S. and beyond. But the “cowboys and Indians” pairing promotes a false distinction; they were not always at odds. Nez Perce bronco buster Jackson Sundown exemplifies this.

Born Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn around 1863, a nephew to famous Chief Joseph, Sundown spent his childhood on and around horses. As a teen, he saw the conflict between his tribe and the federal government erupt in the Nez Perce War of 1877. Surviving the Battle of Big Hole despite his wounds, he lived in Canada before settling on the Flathead Reservation in Montana Territory.

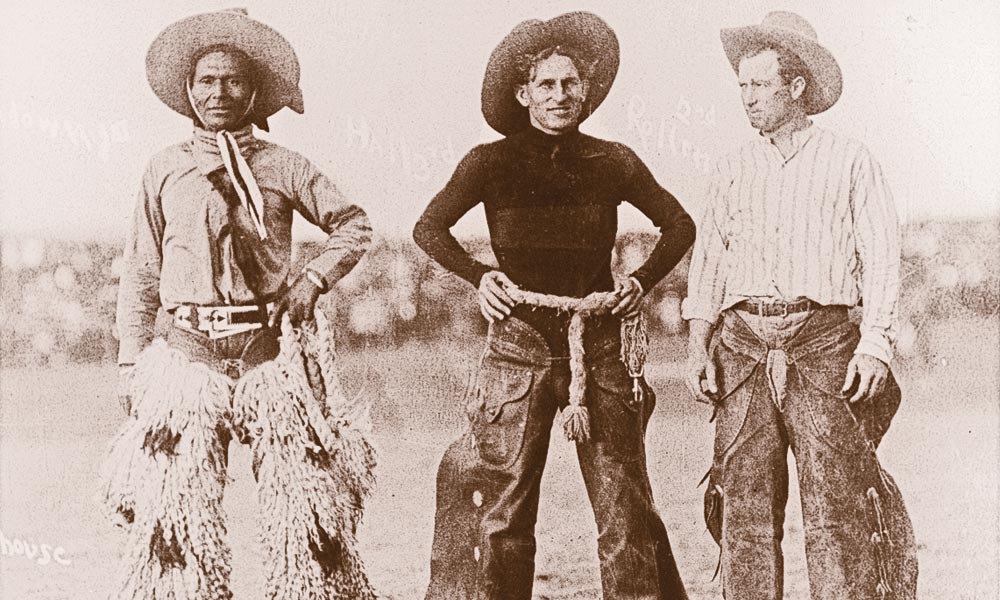

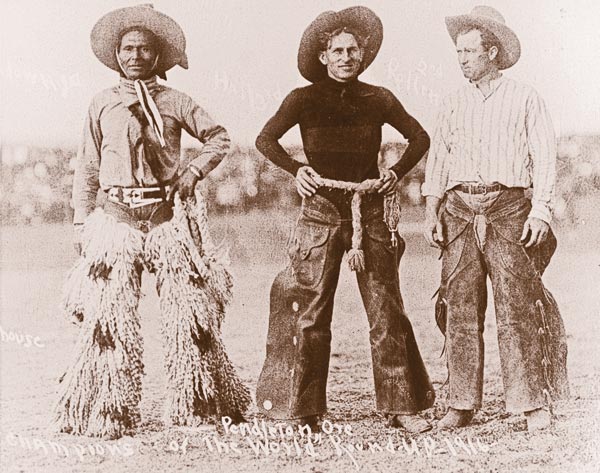

Sundown gained a reputation for his riding skills and began competing locally. When he tried his hand at the Pendleton Round-Up in Oregon, he was already in his late 40s, yet he bested many of the younger entrants and reportedly rode some broncos until they surrendered into standstills.

Sundown’s talent combined with his showmanship and orange angora chaps made him a crowd favorite and endeared him to his competitors. Yakima Canutt called him a “…great man—well respected, friendly, proud, and intelligent.”

– 1910 photo courtesy Buck Wilkerson Collection, R.255.04; 1916 photo courtesy Photographic Study

Collection, 2005.213 –

With grit and determination, he rode at Pendleton year after year, coming close, but never winning the coveted title. Finally in 1916, at around the age of 53, Sundown rode Casey Jones, Wiggles and Angel to victory and became the first American Indian Bronco Buster of the World.

“Before 30,000 people, yesterday the largest single day attendance since Pendleton began staging her famous frontier show, he [Jackson Sundown] proved his right to the title…,” The Daily Capital Journal of Salem reported.

“There was no question in the minds of the spectators at all…. A mighty cry of ‘Sundown, Sundown’ floated out from grandstand and bleachers and, when the judges’ decision was found to conform with their preference, pandemonium reigned.

“Sundown was placed on his horse and rode slowly about the track. The crowd stood en masse, yelling, cheering and waving hats with wild enthusiasm. It was an ovation that a king might have envied….”

– 1910 photo courtesy Buck Wilkerson Collection, R.255.04; 1916 photo courtesy Photographic Study

Collection, 2005.213 –

He accepted the prize saddle and announced his retirement. The world champion spent his later years teaching his skill to children on the reservation, while also posing for artists and photographers.

Seven years after his triumph, when Indians were still not considered to be American citizens, Sundown died of pneumonia at the age of 60. The barrier he broke in 1916 still resonates today. He was not a Nez Perce or a cowboy. He was a Nez Perce and a cowboy.

A fourth-generation Oklahoman, Kimberly Roblin is the curator of Archival & Photographic Collections at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. She contributed to the Oklahoma Nonfiction Book of 2010, Thomas Gilcrease.