The James-Younger Gang was moving up in the world on July 21, 1873. For the first time, they were going to rob a train—one with a very rich load, just outside Adair, Iowa.

The outlaws took their cues from another train stickup in 1865 near Cincinnati. They dislodged one of the rails before the train went into a sharp curve. The locomotive pitched over, killing the engineer. Other cars either turned over or derailed. The gang—wearing masks—easily took over their target.

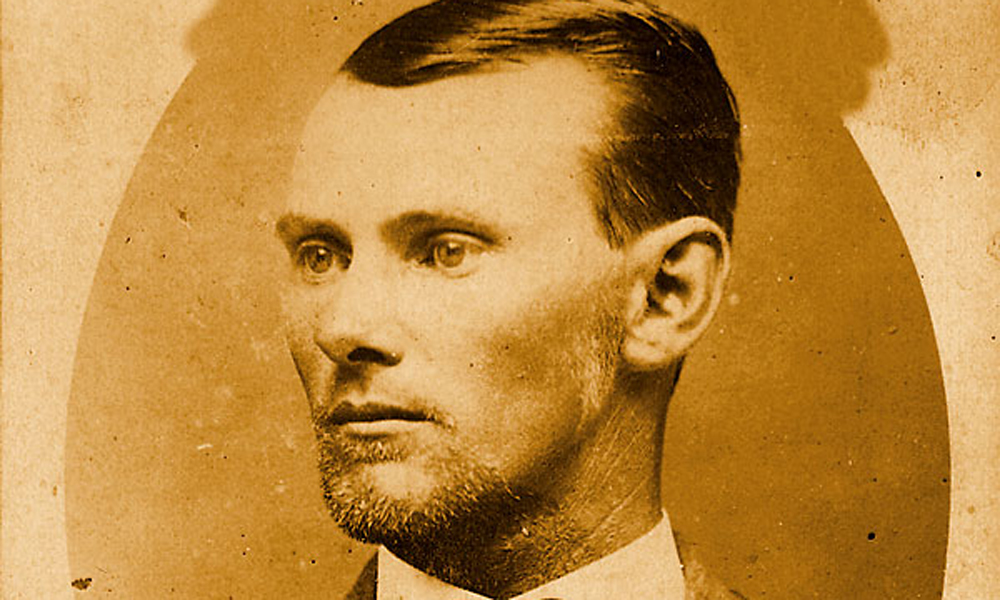

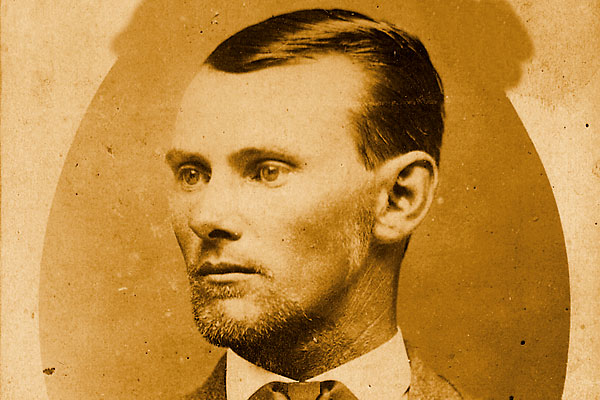

At least initially, the job was well planned and went off without a hitch. Two of the men patrolled outside the train. Two others, including Cole Younger, kept an eye on the passengers. And two went into the express car—Jesse and Frank James. Jesse, in a flamboyant move, tore his mask off as he told the express messengers to open the safes and give him the money. They followed directions; the take was $2,337, much less than Jesse anticipated.

Newspapers earlier in the week had reported that the train carried three and a half tons of gold and silver bullion. It was worth more money than the boys had ever seen, and they wanted it.

But they had no idea what they were looking for.

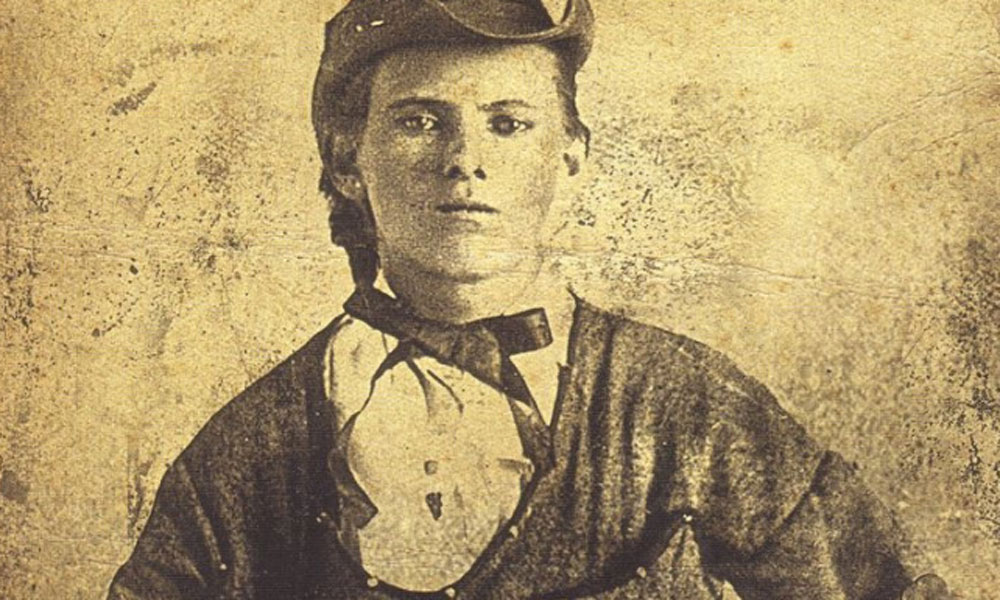

– Jesse James and Jesse James Pistol Courtesy Library of Congress –

Jesse kept demanding, “Where’s the bullion? Where’s the bullion?” The express messenger pointed to the gold and silver bars that were underfoot, but the outlaw leader apparently didn’t understand. Seemingly, Jesse James thought “bullion” was coinage, not large, heavy bars. And even when he was shown the riches, he didn’t get it. The gang wasn’t prepared for it anyway; they would have needed a large wagon or two to haul away the bullion, not the speedy horses that provided their getaway. Even if they’d had wagons, it would have been hard to pass the distinctive bars at a bank or store.

The outlaws decided not to rob the passengers. And before they left, Jesse expressed sorrow over the death of the engineer. They went to their horses and headed out; the whole event took about 20 minutes.

Within four days, St. Louis Police had identified the robbers, who included Arthur McCoy and George Shepherd. The railroad offered $5,000 for their capture. Iowa’s governor tossed in $500 for each bandit. But the outlaws were never caught and tried for the Adair robbery. The outfit, in one form or another, later committed another half dozen train holdups, and most were more successful than their first attempt.

One has to wonder if Jesse James ever realized just what the word “bullion” meant—and what his semantic problem cost him on a summer night in 1873.