— Courtesy Warner Bros. —

Every period picture, consciously or not, reflects two periods, the time in which the story is set, and the time the film is made. Half a century ago, in the summer of 1969, the tumult of the times was inescapable. The “Summer Of Love” of 1967, when hippies and flower-power and LSD were supposed to save the world, had been followed by the ghastly 1968, with the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, riots at the Chicago Democratic Convention, the seemingly endless Vietnam War and, good or bad, the election of President Richard M. Nixon.

— Courtesy Warner Bros. —

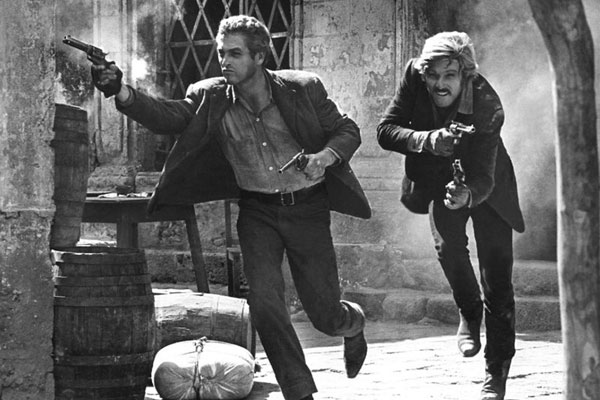

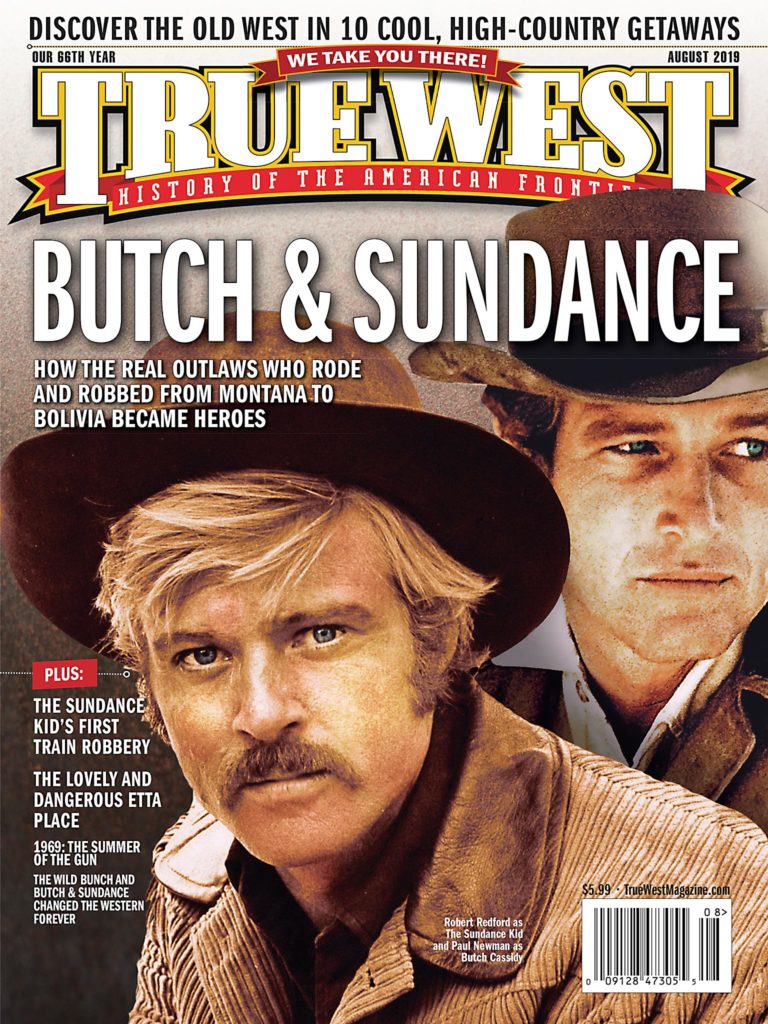

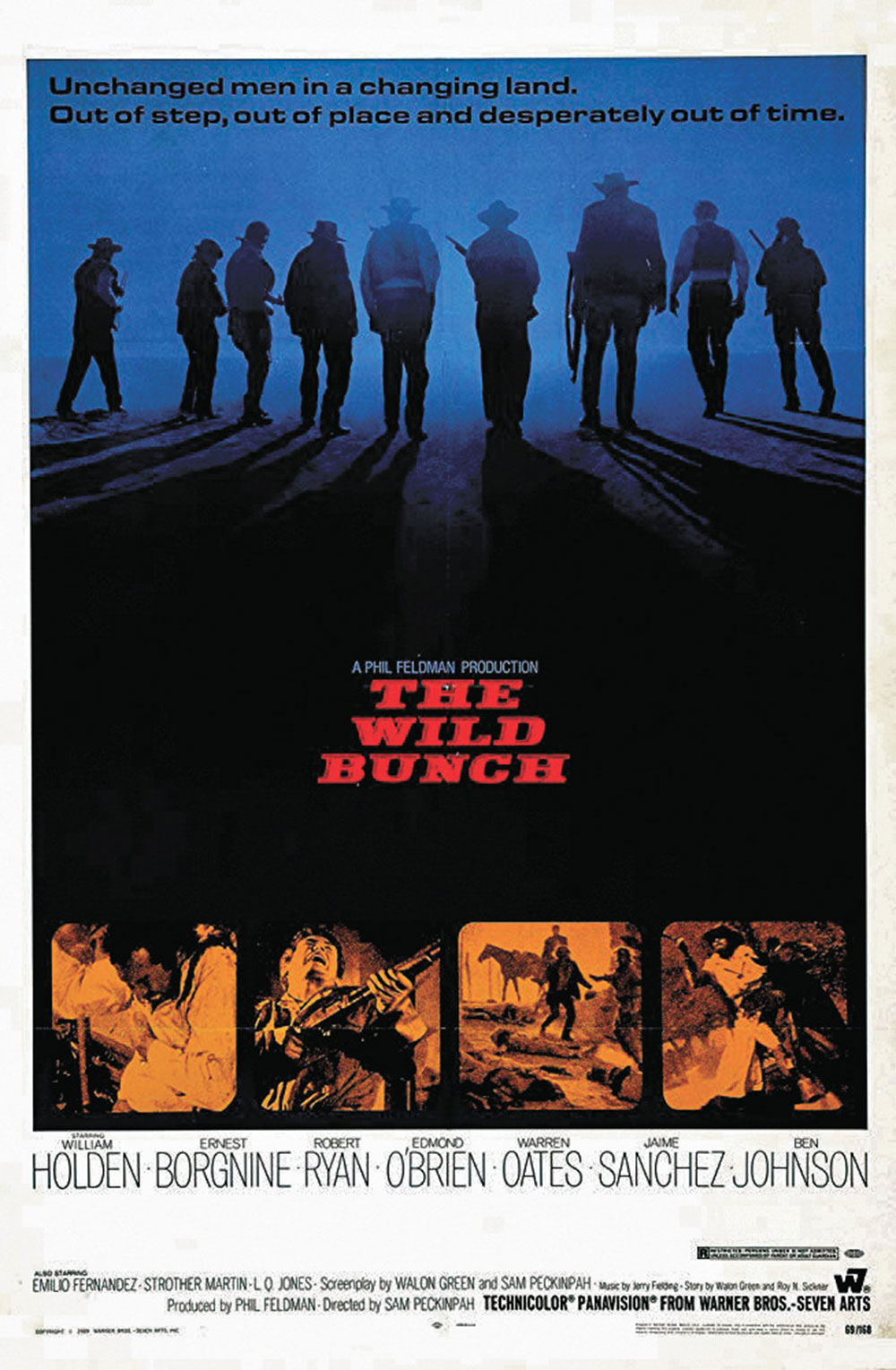

Out of this maelstrom came two Western movies. Each was directed by a TV-trained World War II Marine veteran, each budgeted at the then princely sum of about $6 million, and fictionally recast and enlarged the legendary story of Butch Cassidy’s Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, a.k.a. The Wild Bunch. At the box office, Butch would earn $102 million, four Oscars and three more nominations. Wild Bunch would earn $638,000, two Oscar nominations, and no awards. Two of the finest films of the 20th century, their popularity today is far greater than when they were made, and their influence on films released since is incalculable.

— Photo by Paul Harper, courtesy of Nick Redman and Jeff Slater —

Although the two stories have remarkably different tones, the historical inspirations for the plots are remarkably alike. In the early 1900s, an outlaw gang learns in the midst of a hold-up that they’ve been set up; a railroad magnate has spent a small fortune to assemble a super-posse to track them down and kill them. The posse in Butch is a faceless enemy. In The Wild Bunch they are a big part of the story, led by former associate Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan). The gang flees south of the border. In Bunch, the gang stays together, goes as far as Mexico, and becomes involved with revolutionaries. In Butch, the gang splits up in the U.S., and Butch, Sundance, and Etta flee all the way to Bolivia, and restart their criminal careers.

— Photo by Paul Harper, courtesy of Nick Redman and Jeff Slater —

The longer gestation was for Butch. Novelist, playwright and screenwriter William Goldman started researching the life of Cassidy in the late 1950s. He wrote his first drafts while teaching at Princeton. As he recalls in his book Adventures in the Screen Trade, “The Wild Bunch consisted of some of the most murderous figures in Western history. Arrogant, brutal men. And yet, here running things was Cassidy. Why? The answer is incredible but true: People just liked him.” Goldman loved that while Sundance was a brooding killer, Butch had never even injured anyone during his outlaw career. Goldman had already had success in Hollywood with 1966’s Harper, the Paul Newman detective film, when producer Paul Monash bought the Butch script for $400,000, the highest price paid for a screenplay at that time. It’s frequently been called the best screenplay ever written. It won the Oscar.

— Courtesy Warner Bros. —

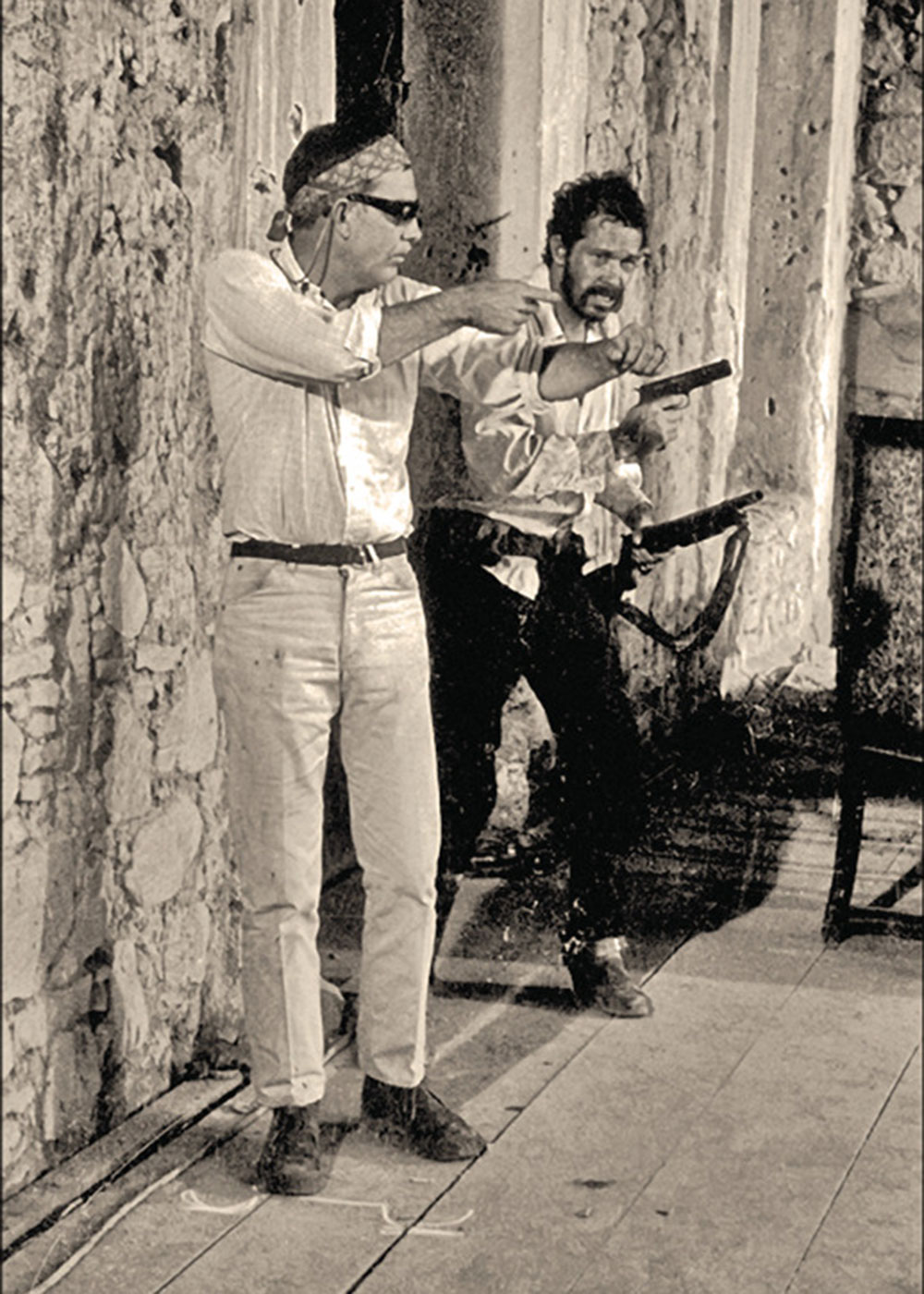

The Wild Bunch was the brain-child of stuntman and Marlboro Man-model Roy Sickner. While not a writer, he’d worked in many Westerns, including Nevada Smith and Peckinpah’s ill-fated Major Dundee. He had an idea for a Western about some outlaws who move down to Mexico to escape the law, and get into more trouble. Though more about action than plot and characters, Peckinpah was encouraging, as was Sickner’s drinking buddy Lee Marvin, a big star since his 1966 Best Actor Oscar for Cat Ballou, who attached himself to the project. Katy Haber, who worked with Sam Peckinpah in various production roles on eight movies, says the story really took shape when Sickner teamed up with young screenwriter Walon Green. “It had been a Civil War film, but it was Walon Green who placed it in the Mexican revolution.” Green, a Beverly Hills kid, had visited Mexico on a nature program as a teen, and fell in love with the country and its people. He went to college in Mexico City, and absorbed the nation’s history. Though then a writer with no movie credits, he had talent and knowledge, and when he teamed with co-writer Peckinpah, they shaped the screenplay into something magnificent.

Sam Peckinpah was on shaky ground when The Wild Bunch came along. Ride the High Country had been a sleeper hit, especially overseas. But his follow-up, Major Dundee, with 42 minutes slashed from Sam’s cut, was not the film he meant it to be, and it bombed. Next, he began directing Steve McQueen in The Cincinnati Kid, but was fired after a week for filming an unscripted nude scene. He was hired to write and direct Villa Rides!, but when star Yul Brynner complained that Villa wasn’t coming off as heroic enough, Peckinpah was replaced by writer Robert Towne and director Buzz Kulick. He hadn’t directed in two years.

— Courtesy Warner Bros. —

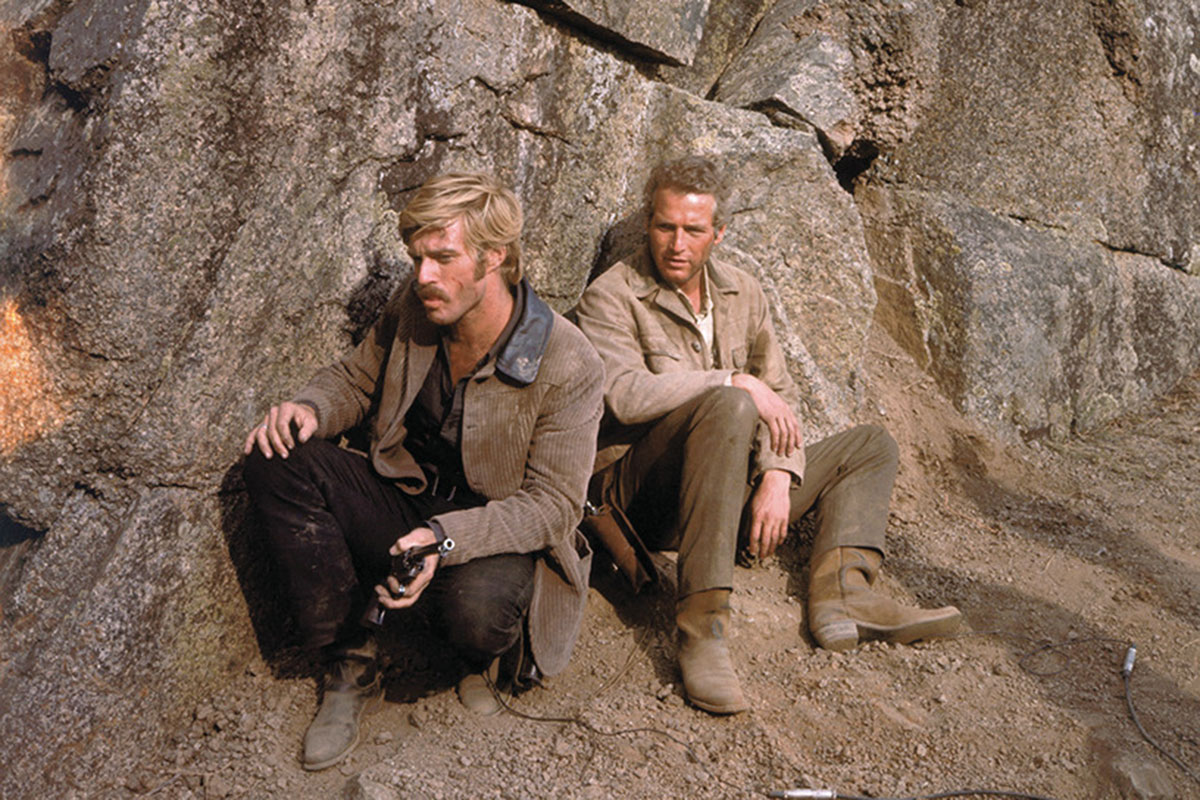

George Roy Hill also had his troubles. Robert Crawford Jr., who would produce eight movies for Hill, and describes himself as “Sancho Panza to his Man of La Mancha,” recalls, “George got fired off Hawaii three times. And he was let go in post-production on Thoroughly Modern Millie.” But unlike Peckinpah’s situation, “Millie was a terrific success. So was Hawaii, and his agent then sent him Butch Cassidy.” Paul Newman and Steve McQueen had been cast as the leads, but with Newman as Sundance. “George [tells] Newman, ‘You’re not right for Sundance. You should be playing Butch.’ Newman says, ‘This is kind of comedy, and I don’t do comedy well.’ George said, ‘No, this is a tragedy, and you’ll be terrific as Butch.’ He convinced Paul to take Butch. McQueen said, ‘That’s great, but I don’t want to play Sundance.’” It may seem surprising that Robert Redford wasn’t the natural choice for Sundance, but until Butch made him a star, he was considered a light comedy actor, not a dramatic lead.

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

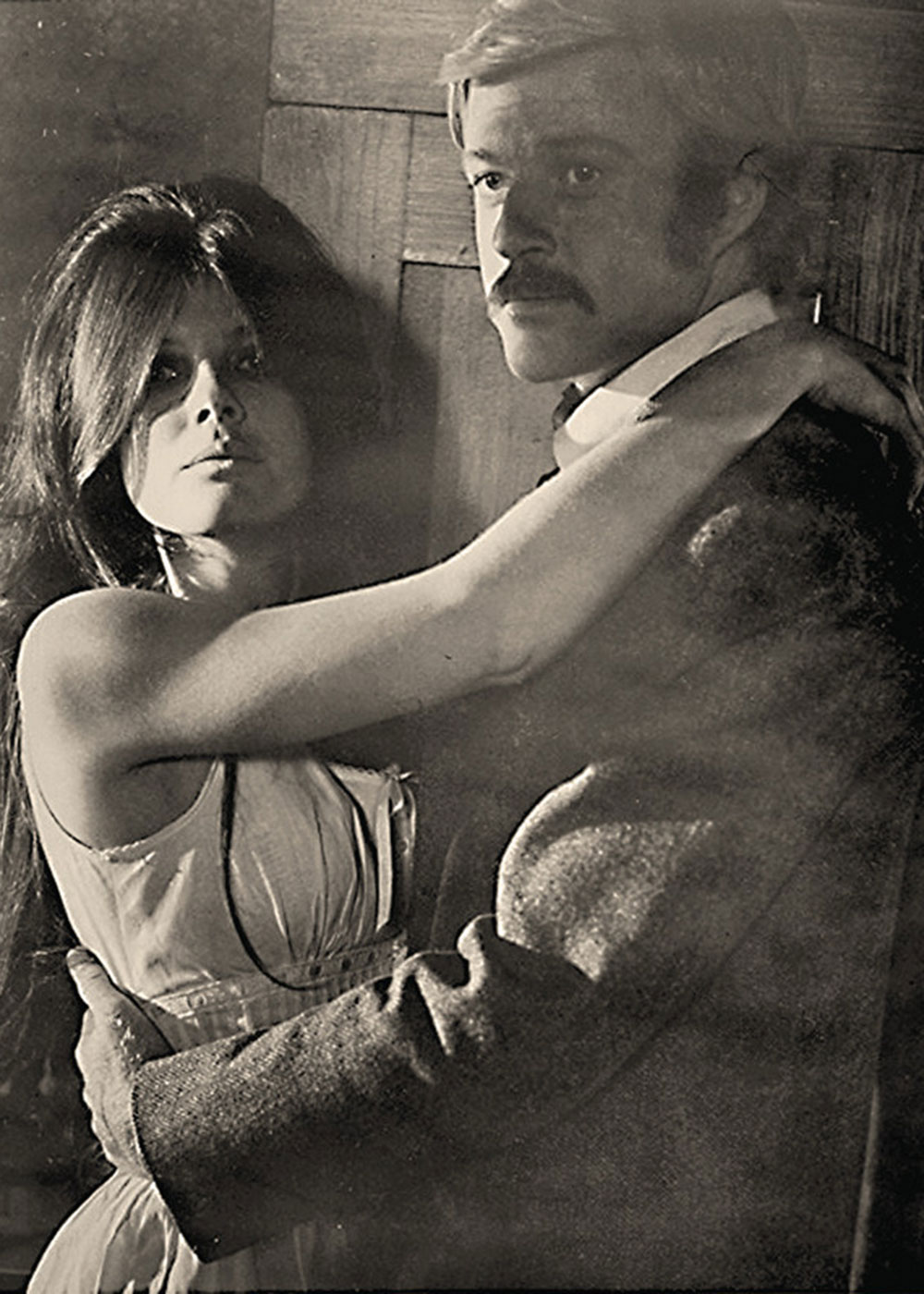

Katharine Ross, who would play Etta Place, recalls, “The first script I got was called The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy.” She was a natural for Westerns. “I started riding when I was seven.” One of the last of the contract players at Universal, she’d guested on many Western series, and her first feature-film role was as James Stewart’s daughter in the anti-war Western Shenandoah. “I really got that because of the Gunsmoke I did that Andy McLaglen [who would also direct Shenandoah] directed.” She got the role of Etta in part because she’d become a star, and an Oscar nominee, for her wonderful performance opposite Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate. Also, as Hill noted in his audio commentary on Butch, “She came on the picture basically because I thought she was the sexiest girl I’d ever seen…just ravishingly beautiful.”

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

As the Wild Bunch script evolved, Lee Marvin began to have real doubts. Pike Bishop was becoming more and more like his character in 1966’s The Professionals, plus same locale, same uniforms; he didn’t want to be typed. When he was offered $1 million to co-star with Clint Eastwood in the musical Paint Your Wagon, he took it. That gave William Holden the chance to give the performance of his career. Fifty, but looking far more world-weary, Holden had been giving repetitive performances in mediocre films; he’d been convicted of manslaughter after a drunk-driving accident in Italy. He knew Pike Bishop’s desperation, when all you have left is pride. He wasn’t the studio’s first choice, but Peckinpah held firm. “You know, Ernie Borgnine wasn’t their first choice either,” Haber remembers. After his Oscar for Marty, he’d squandered his talent on dross like McHale’s Navy. “But Sam was emphatic. Proof is in the pudding in the film—that relationship was brilliant.”

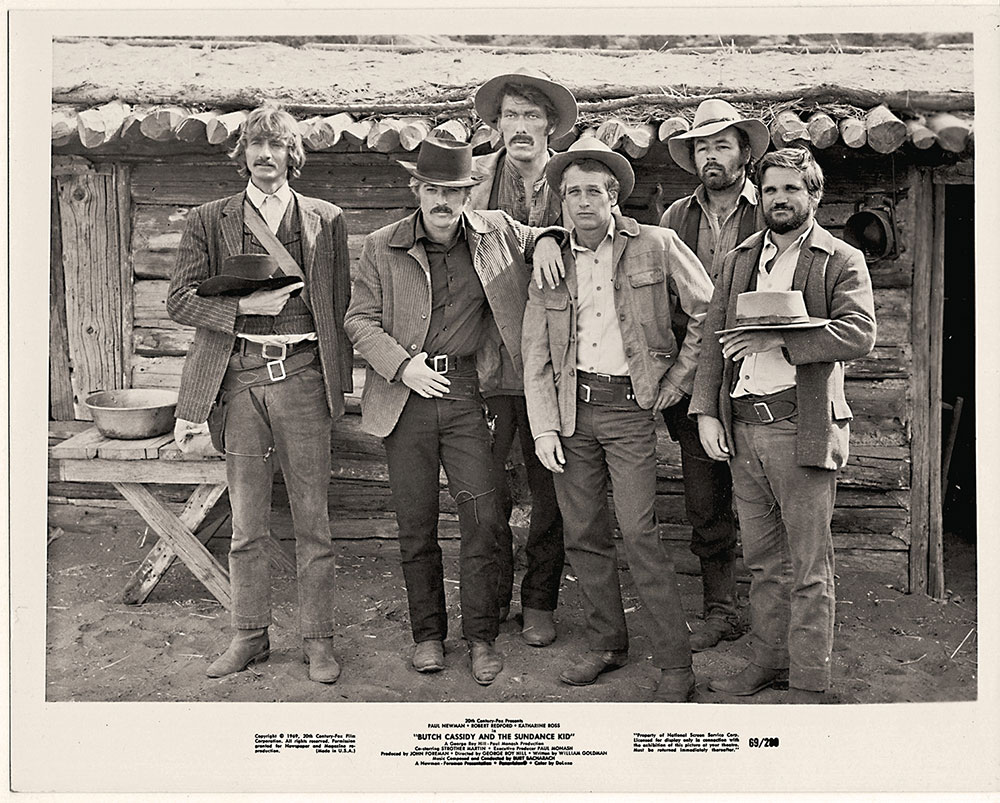

Most of the rest of the cast was made up of Peckinpah regulars, all doing exceptional work. Among the gang were Warren Oates and Ben Johnson, both on the eve of stardom, as the Gorch brothers. As Paul Seydor, director of the Oscar-nominated The Wild Bunch: An Album in Montage, says, “Tell me another movie in which you believe two men are brothers more than in The Wild Bunch.” New to the Peckinpah fold was Bo Hopkins as Crazy Lee, the first of the Bunch to die, but about the last still living, and currently preparing to star in Hillbilly Elegy for Ron Howard. It was an unforgettable time in his life because, he says, “I got to work with my heroes. Bill Holden got me into two pictures. Ernest Borgnine became like a father to me till the day he died. Robert Ryan helped me do my first interview, because I didn’t know what to say.” He remembers preparing for the scene where he holds the railroad customers hostage, forcing them to march and sing hymns, “and Dub Taylor stayed up all night with me, helping me sing ‘Shall We Gather at the River,’ ’cause I hadn’t memorized the whole song.”

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

Between TV and movies, L.Q. Jones appeared in practically everything Sam Peckinpah did, here teamed with Strother Martin as bounty hunters who came off like a degenerate Abbott and Costello. Edmund O’Brien, Oscar-winner for The Barefoot Contessa, has a delightful turn as Freddy Sykes, a geezer who recalls Walter Huston in Treasure of the Sierra Madre, one of Peckinpah’s favorite films. L.Q. recalls, “Eddie was so ill all the way through the picture that I spent two weeks at Eddie’s place seeing they were feeding him right, that he was doing what the doctor told him to. Sam spaced his shooting out so Eddie didn’t have to work two days in a row. He was sweating blood, but he was getting the work done.” Remarkably, O’Brien would recover, and live another fifteen years.

Another great performance was delivered by Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez as Mapache, the terrifyingly erratic rebel leader. A unique figure in Mexican history, Fernandez was a star actor, director and a convicted killer. L.Q. remembers, “He was also a military hero for Mexico. He came in one day to get me, and I was studying at my Spanish. He loved it, so after that, every day I came to his place so he could teach me some more Spanish. But I was petrified of the man, because the first day on the show, he tried to kill a waiter for giving him the wrong food.”

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

The music from the two films could not have been more different. Jerry Fielding composed the score for Wild Bunch and five other Peckinpah films. W.K. Stratton, author of The Wild Bunch, the definitive book on the film, notes, “Jerry went to Mexico and researched the actual music that was being played during the revolution and then wrote his. The Wild Bunch has 85 minutes of music in it.” Fielding’s score was Oscar-nominated. Hill wanted a contemporary feel to Butch Cassidy, and that included the score by Burt Bacharach, which was focused on three lyrical music sequences. Crawford reveals that when Hill gave them the rough-cut to work with, he’d cut the famous bicycle scene to Simon and Garfunkel’s “59th Street Bridge Song,” a.k.a. “Feeling Groovy.” Bacharach would win Oscars for the score and the replacement song, “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head.”

Ross reflects, “[One] of the most memorable parts, for me, is the bicycle ride. [It] was done with a very long lens and, and the only direction we got was whether we were going left to right or right to left across frame. So we were left to our own devices; it was very improvisational. It is very uncomfortable riding in an orchard on the handlebars

of a bicycle.”

That wasn’t the only uncomfortable situation for Ross on the shoot. She was watching cinematographer Conrad Hall, who would win the Oscar for Butch, shooting the sequence where the super-posse bursts from the train. “I was going with Conrad at that time.” He invited her to operate one of the cameras. “It was the last shot of the day. There were six cameras, and I was on camera six, an Arriflex on a McConnell head, just panning along. George Roy Hill decided to sit near the camera I was operating, but he never said anything. Back at the motel, the production manager said, you have a very angry director on your hands. I got banned from the set except when I was working.” Considering how male-dominated the Camera Union was at that time, Katharine Ross may very well have been the first woman to be a camera operator on a Hollywood movie.

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

Lucien Ballard was Peckinpah’s cinematographer on The Wild Bunch and eight other shows, and his work was phenomenal. Notes Seydor, “He would set up four cameras and they would often be shooting at four different speeds.” This was particularly crucial for the elaborate shoot-outs at the beginning and end of the film, for which Peckinpah and editor Lou Lombardo masterfully alternated between standard speed and various degrees of slow motion, to make the viewer hyperaware of the destruction and slaughter. No action-film since The Wild Bunch has not been influenced by Ballard’s photography and Lombardo’s editing.

While the leads in both films die in the end, the filmmakers deal with it very differently. Peckinpah showed it in brutal detail. Hill did not want to see his heroes torn with bullets, and decided on a freeze-frame, with the audio of gunfire continuing. While the Wild Bunch’s last few speeches were dramatically terse, Butch and Sundance, even when mortally wounded, kid each other rather than talking about their dire situation.

Crawford remembers the first preview of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid in San Francisco. “People were laughing right up to the end of the movie, when they were all shot up, and about to charge out. Everybody was elated, all the applause, all the executives saying, ‘It’s a winner! It’s wonderful!’ And George was that little guy with a cloud over his head. And he looked at me, and said, ‘They laughed at my tragedy.’”

Henry C. Parke, Western films editor for True West, writes Henry’s Western Round-up online. His screenplay credits include Speedtrap (1977) and Double Cross (1994), and he’s done audio commentary on a fistful of Spaghetti Westerns.