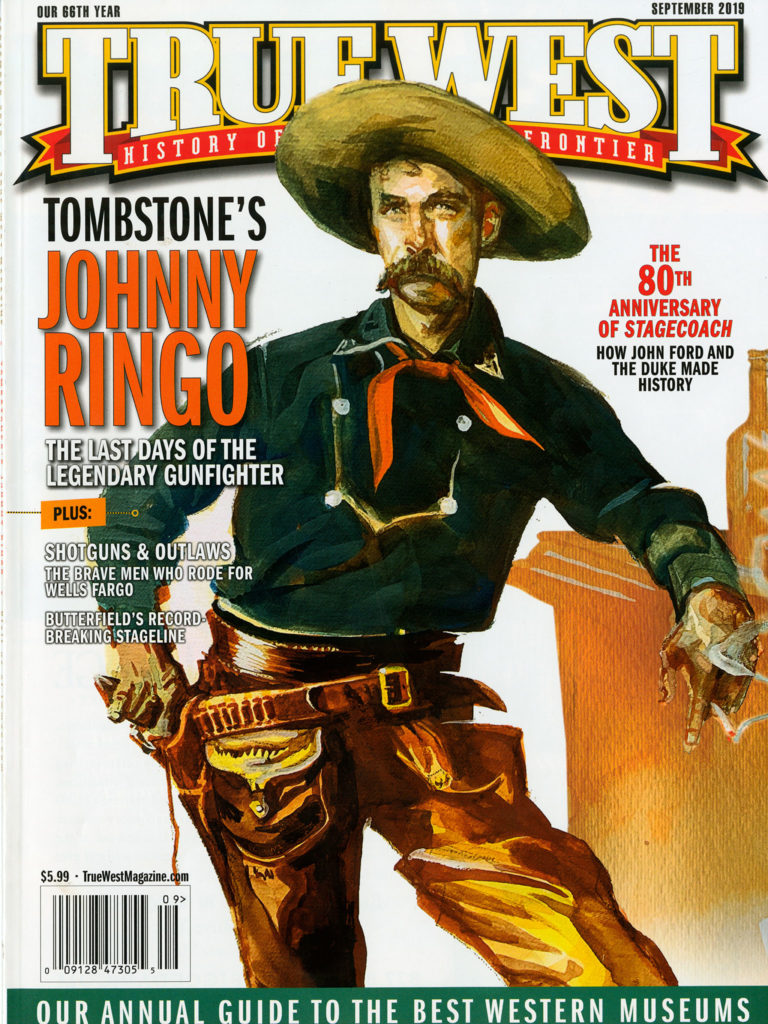

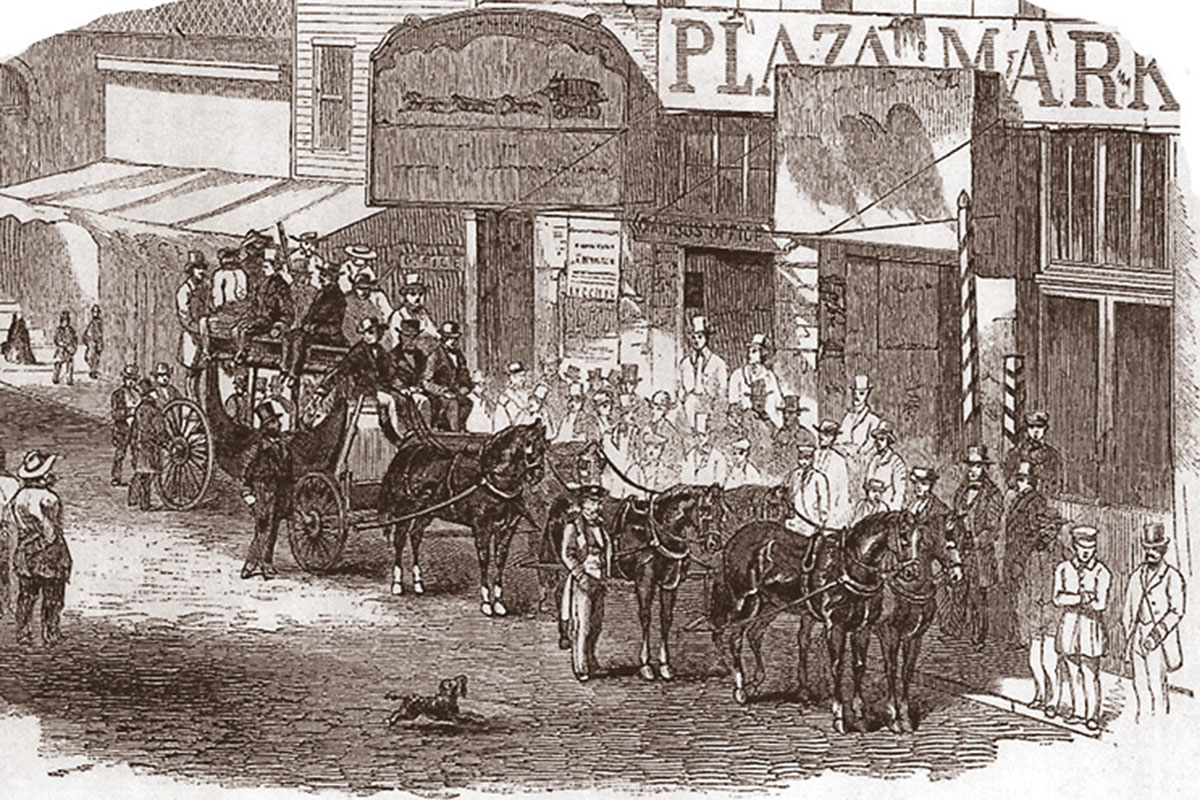

John W. Butterfield’s highly anticipated moment in the sun lost its luster quickly. In Tipton, Missouri, he had planned to carry the canvas mailbags personally from the late-arriving St. Louis train and then sling them into the awaiting stagecoach. Within moments, the messages would gallop across country, all the way to San Francisco, 2,795 miles—a first endeavor of its kind. With that act, he would open the world’s longest transcontinental mail line.

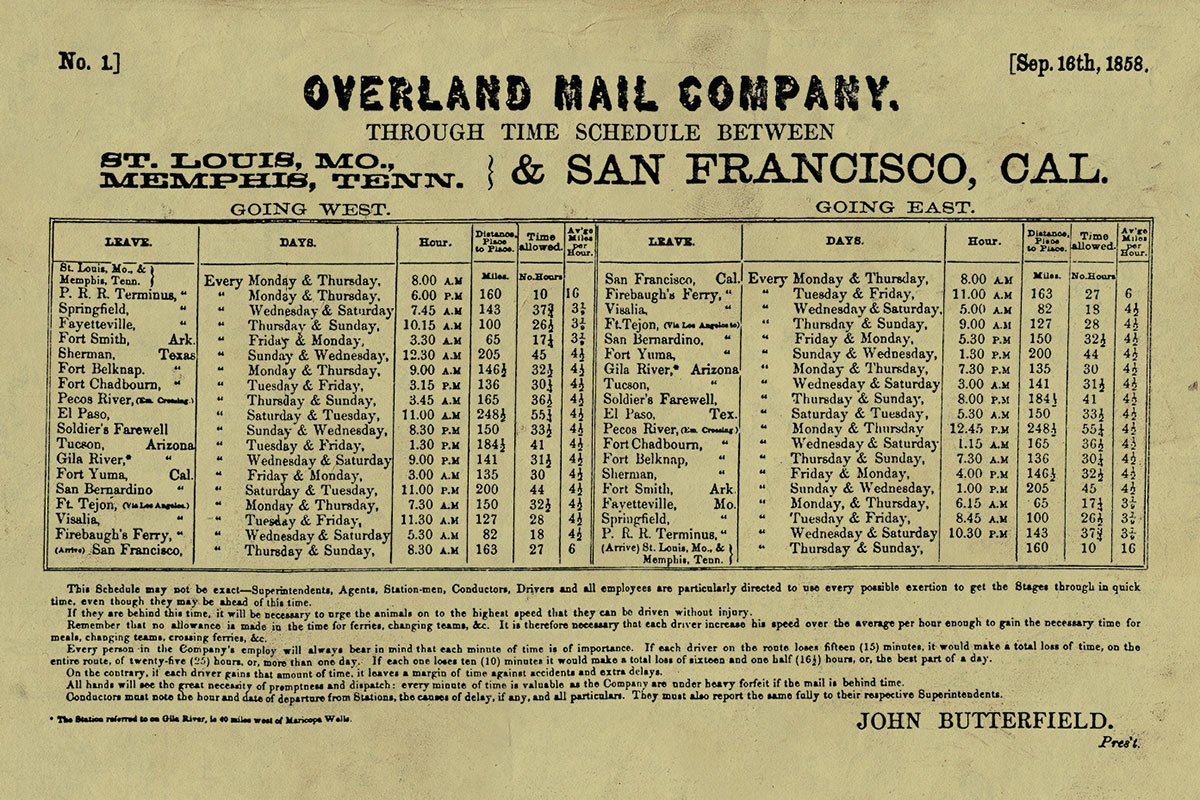

But the train conductor hadn’t waited for 56-year-old “Old John,” as he was affectionately known. Already, the bags had been unceremoniously dumped into the stage. Undaunted, on September 16, 1858, John Butterfield himself climbed aboard the first westbound stage, driven by John Butterfield Jr. With a yee haw and step up now boys, the first two Overland Mail Company stagecoaches set out from opposite ends of the line—the eastbound from San Francisco a day earlier.

— Inserts Courtesy True West Archives/Map of Butterfield stage route courtesy NYPL Digital Collection —

Indeed, in the mid-19th century, when land and opportunity in California beckoned and Americans answered, the only way to send and receive mail coast to coast was by sea. Mail sent down either coast to Panama was carted across the boggy, tropical Isthmus, taking two to four weeks, weather permitting. Loaded onto a steamer, mail, parcels and people then continued on to their destinations. A trip of four months was not unusual. Not good enough, people complained.

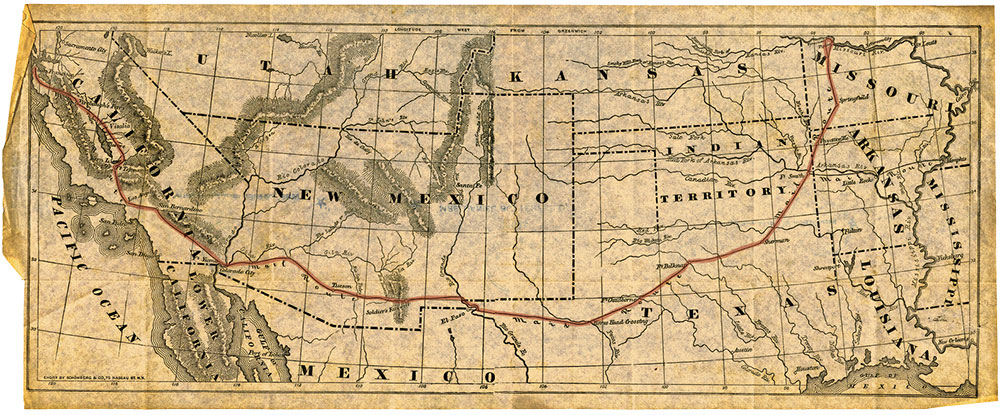

Surprisingly, Congress took note and on March 3, 1857, authorized Postmaster General and former Tennessee Governor Aaron Brown to contract for mail service from Missouri to California. The U.S. Postal Office advertised for bids. A few requirements were: (1) begin operation within one year; (2) use the selected “all weather, no mountain” southern road; (3) create a spur line or “bifurcated” course to Memphis, Tennessee; (4) cost no more than $600,000 annually; (5) provide semiweekly service; (6) deliver mail on each trip within 25 days. John Butterfield, friend to incoming president John Buchanan, won the bid—he and his associates signed a six-year contract on September 16, 1857—and the stage was set for the first efficient transcontinental mail service.

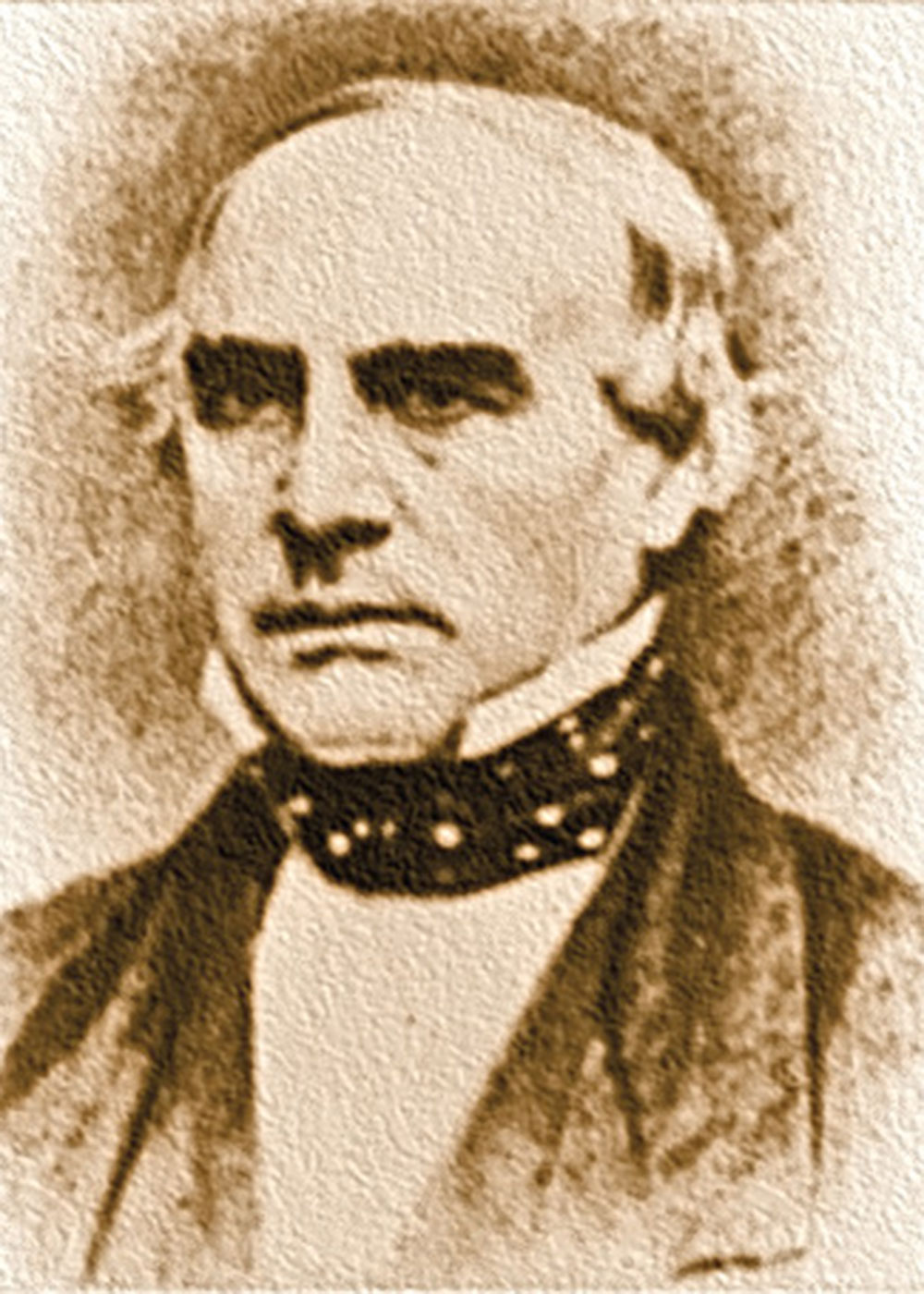

Born in Berne, New York, on November 18, 1801, John Warren Butterfield drove his first stagecoach at age 19 in Albany, New York, and then in Utica, where he would be elected mayor in 1856. Heavily involved in mail and passenger lines in upstate New York, he organized the Butterfield, Wasson & Company in 1849. The next year he merged his business with Wells & Co. and Livingston, Fargo & Co., to form the Wells and Fargo Company and also, the American Express Company.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

Butterfield’s unparalleled work ethics made him the right man to be president of the Overland Mail Company (OMC). The two starting points, St. Louis and Memphis, would converge at Fort Smith, Arkansas. The route would then run through Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), over the plains of Texas to Franklin (near El Paso), across arid New Mexico Territory (Arizona Territory not yet created) to Tucson, and then enter California at Fort Yuma on its way to Los Angeles and then north to the western terminal at San Francisco.

Naturally, Northerners objected. The Sacramento Union, based in the capital city missed by the southern road, called it a “foul wrong,” “an outrage upon the majority of people of the state” and “a Panama route by land.” The New York Press condemned it as “one of the greatest swindles ever perpetuated [sic]upon the country by slave-holders.” Opinions were noted but disregarded, and the U.S. Postal Office pushed forward.

Within twelve months, Butterfield:

• Bought 1200 horses and 600 mules (each branded with OM—Overland Mail), then distributed them;

• Ordered 250 wagons;

• Procured several thousand tons of hay and fodder;

• Built 200 way stations every 20 miles;

• Dug 100 wells;

• Surveyed 2,800 miles, graded fording sites, opened new roads or improved old ones;

• Hired a thousand men as surveyors, conductors, drivers, blacksmiths, etc.;

• Created the run schedule.

Butterfield’s credo resonated through the company: “Remember, boys, nothing on God’s earth should stop the United States mail.” Indeed, letters and packages (never payroll or valuables) were delivered in a timely fashion. By the outbreak of the Civil War, OMC stagecoaches were delivering more mail (at 10 cents per half ounce—$3.12 today) to and from the West Coast than all of the ships combined. Early on, Butterfield and his associates decided the deliveries would be more profitable if they took on passengers as well. Travel was not inexpensive—10 cents per mile or full one-way for $150 ($3,116 today).

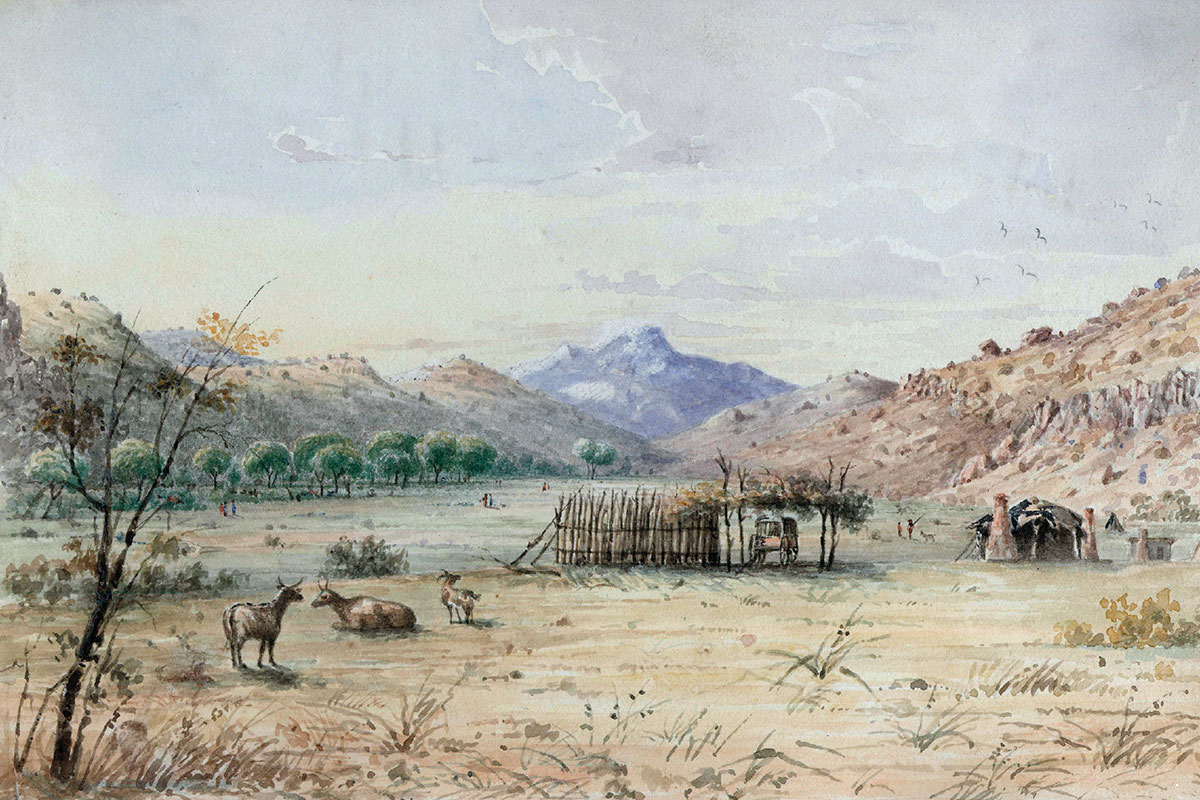

— Courtesy Melody Groves Collection —

Heavy Concord stagecoaches built in Concord, New Hampshire, ran in the eastern section of the route. They proved excellent for more established roads, but crossing the desert required the lighter Celerity coaches, built by Abbott Downing Company in Troy, New York. Passengers on both coaches sat with their knees dovetailed or in the back of the people in front of them (imagine 25 days and nights sitting in a professional ballpark seat). Raphael Pumpelly, who traveled west to Tucson, recounted his ride: “… and there being room inside for only ten of the twelve legs, each side of the coach was graced by a foot, now dangling near the wheel, now trying in vain to find a place of support… Unusually heavy mail in the boot, by weighing down the rear, kept those of us who were on the front seat constantly bent forward…”

Butterfield’s Grand Adventure changed travel as it was known prior to 1858. For

the first time, passengers rode 24/7, teams changed every 15 to 25 miles. Before this, passengers as well as the coach and horses stopped for the night, often camping along the road.

Home stations were built to accommodate hungry passengers. They would find food there for $1. Meals consisted of bacon, beans, onions, coffee and meat. The stop lasted no more than 45 minutes. Fresh drivers took the reins there. Passengers at way stations, where only the team was changed, were asked to “wash their faces” quickly and were allotted five minutes for a much-needed stretch.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

Butterfield’s mail traveled over land (as opposed to over sea) in fewer than 25 days. Fact is, the first run east to west was accomplished in 23 days, 23 hours. Never in the history of North America, or the world, had packages and passengers traveled so far so quickly—and without any major incidents despite bad weather, changeable terrain and Indian attacks. Everyone arrived safe and sound.

The route became such a reliable service that Britain sent official mail headed for Canada via the OMC. The company never hauled “express” shipments—valuables such as payroll, gold, silver and such. That was left up to Wells, Fargo & Co. (yes, the same company as today—note the stagecoach logo).

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

As successful as the enterprise was, the end of OMC came much too quickly. Three major events merged to end the longest mail route. First, dissension in the company pushed Butterfield out as president in1860. It’s believed other board members wanted to run express and he did not. Butterfield was a natural leader, and so with his removal, morale immediately sagged.

Second, a recently promoted Lt. George Bascom was sent to oversee Indian relations in newly formed, provisional Arizona Territory. In February 1861, he botched a deal with Cochise, killing the Apache leader’s brother, thereby causing Cochise to rampage against anyone crossing his territory. Previously, Cochise allowed people to pass through and even had a trading agreement with the way station manager at Apache Pass, near present-day Bowie, Arizona.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

But the decisive death knell proved to be the Civil War. In March 1861, Confederates shut down the route through Texas, which took eight days to traverse, thus cutting the line in half. Mail and passengers were stopped at the Indian Territory/Texas line.

Many we take for granted today, but Butterfield is responsible for several firsts including:

1. Created stage stations, today’s “rest areas” and “truck stops.”

2. American history of El Paso originated with the Overland Mail.

3. Los Angeles grew, once connected with the world.

4. Longest stagecoach line in the world under one management.

5. The first truly transcontinental traffic line on the continent.

6. Strict adherence to schedule for the entire period.

7. Drivers assigned to small sections of the route while mail and passengers went through.

8. Unequaled safety record.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

John W. Butterfield changed the world back then and left quite a legacy. Today’s recuperative rest areas on the Interstates are a direct result of Old John’s creative thinking. Later, the Harvey Houses for the trains were undoubtedly influenced by Butterfield. They provided the same service, for the same reasons, as did the OMC. Quite common to us today, but new to pre-Civil War thinking was operating on a regular schedule with coordinated clock management. Not until the OMC insisted on uniform hours from coast to coast did people consider the need for time zones. In 1869, when train travel stretched across America, Butterfield’s concept of regular schedules and reliable times was quickly embraced.

John W. Butterfield left a legacy we all enjoy today.

Award-winning author Melody Groves wrote Butterfield’s Byways: America’s First Overland Mail Route Across the West.