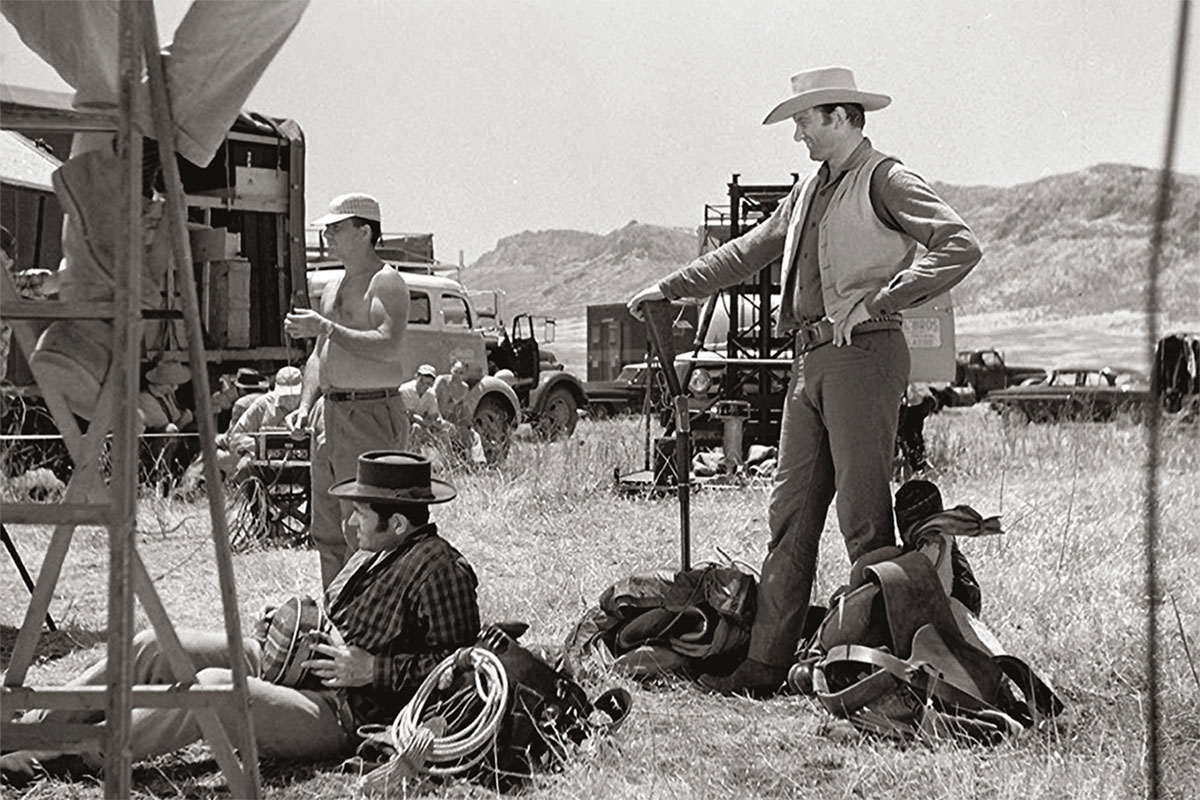

— Courtesy CBS —

With 635 television episodes, 480 radio shows and five movies, no other series in any genre has equaled the longevity of Gunsmoke. And to fans who read credits, Jim Byrnes is a familiar name, having penned 34 of the very best episodes, and one of the movies.

The Iowa-born writer always knew what his specialty would be. “I loved Rawhide, Wanted: Dead or Alive, and of course I loved Gunsmoke, never dreaming I’d ever write for Gunsmoke. I was in high school when I sold my first script.” His older brother Joseph was taking a writing course at Los Angeles Valley College from prolific Western telewriter Richard Carr. “My brother said, ‘They want us to write something, and you watch all the Westerns. Any ideas?’ We wrote a story called Desert Flight. Carr read it and said, ‘You guys should submit it: this is pretty good.’” It became an episode of Zane Grey Theater, “and James Coburn and Dick Powell starred. Then I didn’t sell anything for six years.”

Byrnes wrote scripts on speculation, and drove taxis and trucks until his script, Gaucho, landed him an agent. Gunsmoke producer John Mantley read Gaucho, and called Byrnes in. “They said, we want you to write a Gunsmoke. Come up with a story.” The problem was, they’d already been on for 13 years. “I started pitching stories. ‘We did that 10 years ago.’ I think, this is my great chance; I can’t blow this. I finally found this story about a wolf.” The episode became “Lobo,” and the late Morgan Woodward, who was Gunsmoke’s most frequent guest star, named it his favorite. He recalled with a laugh, “Watching it, I got so involved, I forgot I’m watching me!” [Editor’s note: Morgan Woodward died at 93 on February 22, 2019.]

Before Byrnes had finished writing “Lobo,” Mantley offered him a six-week job as story consultant. “I said yes. Then they said, ‘We want you to stay,’ so six weeks turned into two years.”

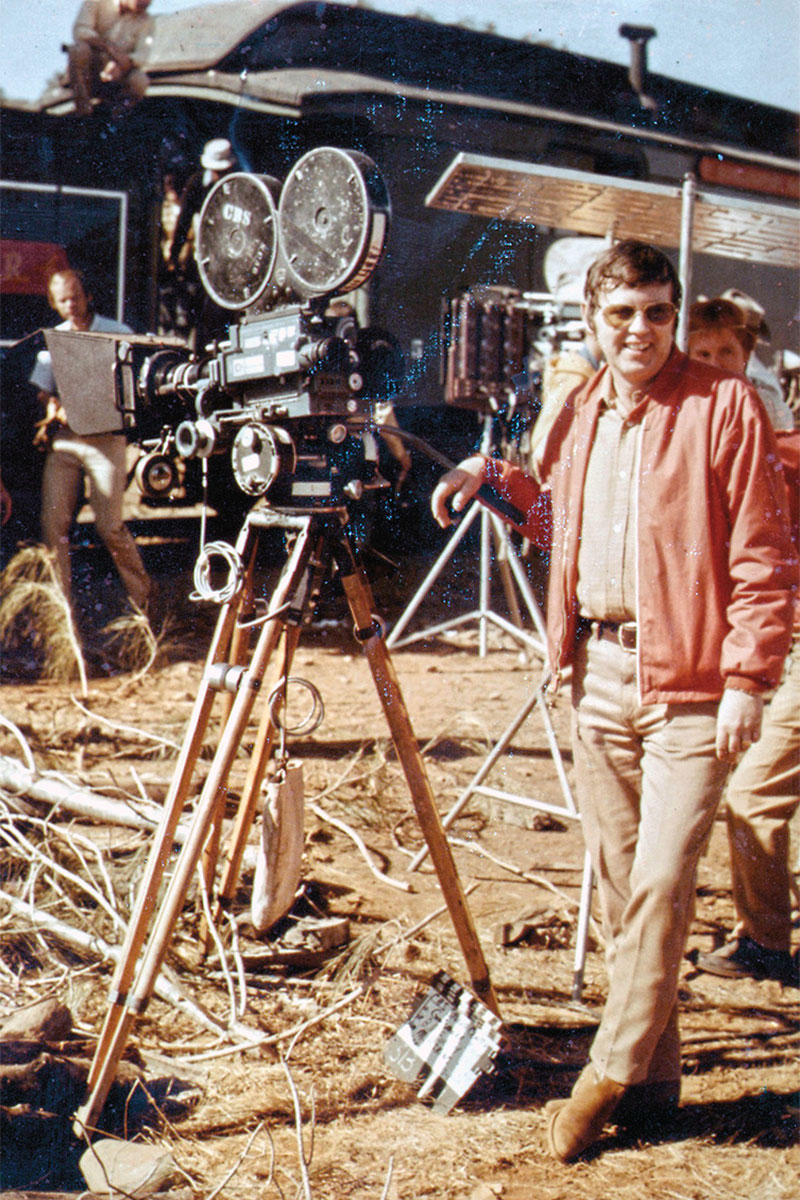

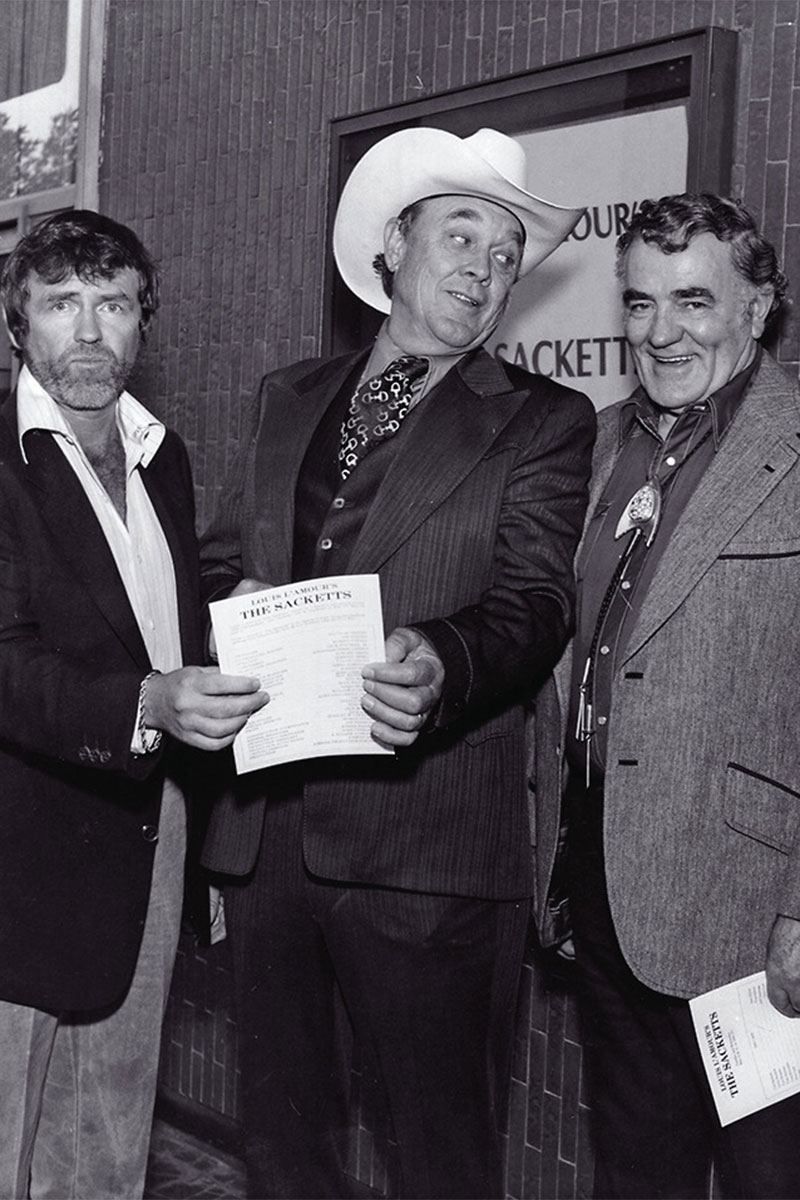

— Courtesy Jim Brynes —

The late 1960s was a tough transitional time for TV, especially Westerns. The back-to-back assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy led to demands for less violence onscreen. “They had to change the opening of the show: Matt in a shoot-out [became] Matt riding a horse. We were warned constantly about violence—the network called me Mr. Blood-and-Guts because I kill a lot of people.”

While Dillon was making mostly cameo appearances, Arness preferring to spend his time surfing, Byrnes’s skills often earned him plum assignments with Dillon in the center. “The Badge” is one of the few shows to deal with the Matt Dillon/Miss Kitty romance. Byrnes also tackled history that was uglier than TV generally dealt with, as in one of his several two-parters. ‘“The Valley of Tears’ was a real place. Indians would raid ranches and farms, kidnap the women, then meet in the Valley of Tears with the Comancheros, who’d trade for them, to sell them into prostitution in Mexico. I got really pissed off when they changed the title to ‘Women for Sale.’”

Another element common in Byrnes’s stories, but rare in the black hat/white hat world of Westerns, is moral ambiguity. By the end of “Women for Sale,” our sympathies have turned against a girl victim, in favor of her young kidnapper! Byrnes’s episode “Thirty a Month and Found” won Best Episodic Drama from The Writers Guild, and the Spur award from the Western Writers of America.

In 1976, MGM came calling, asking him “to do a series based on the movie How

the West Was Won.” They screened the original movie, “but it was too episodic, and I wanted a family. I did what they call a [series] bible, almost 100 pages, with storylines for the first season.” James Arness wasn’t considered for the lead, but when Gunsmoke was abruptly cancelled, its star was a natural for Zeb Macahan.

— Courtesy Jim Byrnes —

The Sacketts miniseries made a star of Tom Selleck in 1979. “Based on two Louis L’Amour books, and Ben Johnson’s character wasn’t in both books. I had to do a lot of shuffling to get to it work. I met Louis L’Amour several times, and what a gentleman. That was a great experience because of Tom, Sam Elliott, Ben Johnson, Glenn Ford—it was a dream, all those guys!”

In 1980, Byrnes turned Kenny Rogers’ hit song “The Gambler” into a Western. “We hit it off very well. Kenny was very humble; he’d never acted before. I said, ‘I think we could be friends for a long time.’” They did The Coward of the County, then Rogers did a Western with another outfit. One of Byrnes’s frequently used actors told him that when they arrived on-set, “they all got notes saying, do not speak to Kenny Rogers unless he speaks to you. Including Ben Johnson, who’d won an Academy Award.” Byrnes wrote the second Gambler movie, but left the final three to others (including editor Stuart Rosebrook’s late father, Jeb Rosebrook, who shared the writing credit on the third and fourth installments of The Gambler).

Over the years, Byrnes has written numerous Western TV movies, and pilots about gunfighters, Buffalo Soldiers, and a rodeo story that starred Slim Pickens and Bo Hopkins. Looking back on nearly 60 years of screenwriting, Byrnes recalls, “The movie that really got me into Westerns was Red River. I saw that, I said, I gotta do this. I’ve got to do Westerns.” His new Western novel, Heller, with Larry Manetti, is available in paperback and Kindle.