On a blisteringly hot Saturday in mid-June 1876, Brig. Gen. George Crook fought to the draw Sioux and Northern Cheyenne warriors led spiritually by Sitting Bull and passionately by Crazy Horse. It was a big fight on a sprawling field. Heroics scored action on both sides. Casualties were pronounced. At battle’s end, Crook held the field and proclaimed a victory. Warriors in Sitting Bull’s camp on Reno Creek, 20 miles away, conceded the Army’s victory, momentarily anyway, until watching Crook’s soldiers ride away. At that moment they knew that victory, in fact, was theirs.

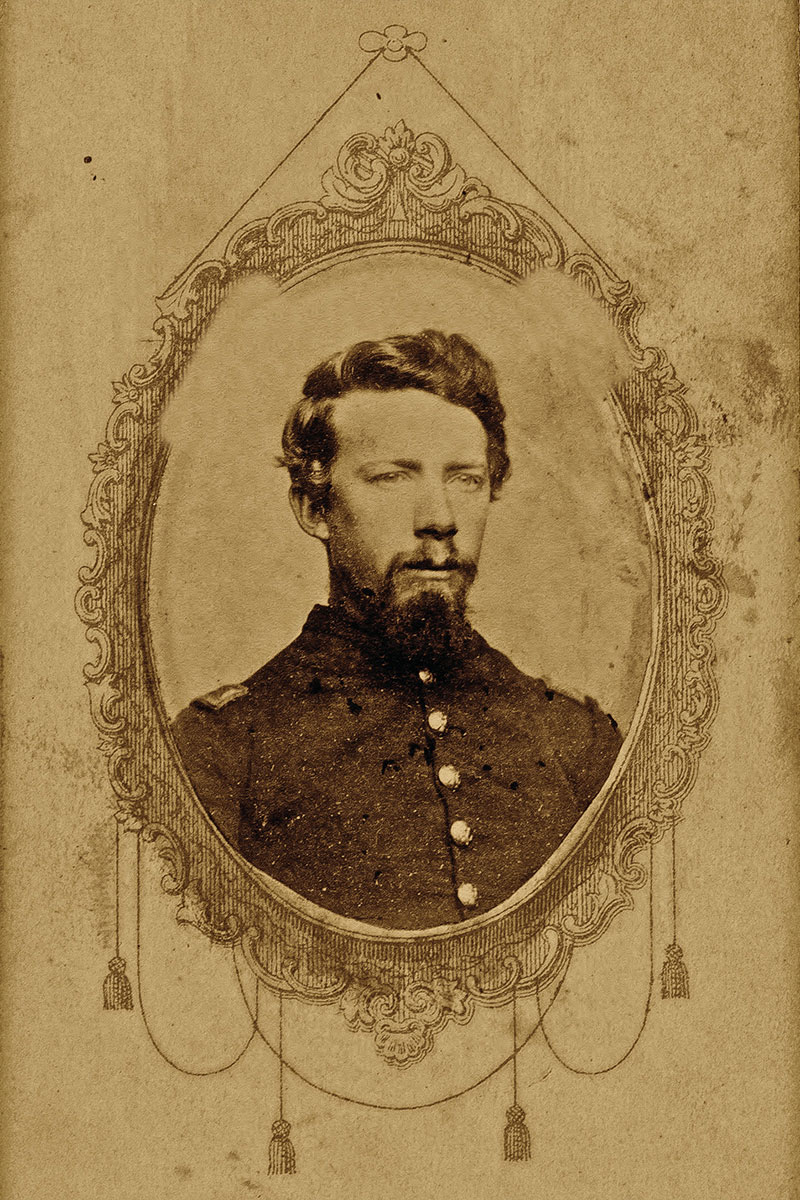

— Courtesy Mark Kasal Collection —

History tells us more. Eight days later George Armstrong Custer, commanding all 12 companies of the Seventh Cavalry, struck this same village, enlarged now and having relocated to the Little Big Horn River. There, Custer and five companies of the Seventh plus nearly three score soldiers more perished. Crook, meanwhile, blithely fished and hunted in the Big Horn Mountains awaiting reinforcements and resupply. He learned of the Custer disaster on July 10, the news delivered by courier from Fort Fetterman. Captain Anson Mills in turn carried the news from the camp to Crook in the mountains, and recalled his look of mortification, “a feeling that the country would realize that there were others who had underrated the valor and numbers of the Sioux.”

Attitudes in Crook’s Goose Creek camp turned instantly against the general. Many were already critical of his leadership on the Rosebud battlefield, but before July 10 focused their enmity on the costs and conduct of that fight alone, reflected in the casualties, the reputations of participating officers and regiments, and the unseemliness now of fishing instead of fighting. All debated notions of victory or defeat. That Crook repulsed his attackers and held the field smacked of a victory. Withdrawing to Goose Creek to tend his wounded and reinforce and resupply seemed a logical move, at least at first, but a decision wearing thin as June turned to July. The Custer disaster changed everything and served to harden the case that Crook could have and should have done more, something, anything offensively that might have averted the calamity at the Little Big Horn. But what might that action have been? One can imagine many alternatives.

On the afternoon of the battle, at the mouth of the Rosebud Narrows, Crook implored his Crow and Shoshone scouts to lead his column through the cañon and charge the Indian village that surely lay at that defile’s other end. All evidence to that moment reinforced this simple belief. The Crows had first told Crook of their enemy’s whereabouts when they arrived at his camp on Goose Creek on June 15. Sitting Bull, they said with utmost confidence, was on Rosebud Creek. Indeed, on that day he was. Importantly, too, all day long the battle had played by way of the Rosebud Narrows. When Sioux warriors fell upon Crow and Shoshone scouts and chased them—from the cañon southward and westward over the heights, through the Gap, and across the foreground between the east-west reach of the stream and the Camel-Back Ridge—they reinforced the notion of a village lying somewhere down the Rosebud. This belief was bolstered yet again when Mills and Noyes traveled most of the way through the Narrows on Crook’s order to find and attack the village at the other end of the cañon. Nearly one and all in the column were awed, even dumbstruck by the buffalo tracks scoring the dry, soft earth, tracks quickly discerned as Indian pony tracks instead. The attackers that day had come up the Rosebud from a village that simply had to be located down the Rosebud.

But Crook’s Indian scouts refused to go with him on the afternoon of June 17, partly fearing the peril of the Narrows. They offered excuses, not the least that the Narrows amounted to a massive trap. That Mills and Noyes had just traveled that same ground barely an hour before and sensed no trap at all was immaterial. The auxiliaries were adamant. A year later, Crazy Horse played into this thinking. In an interview occurring at Red Cloud Agency shortly after his surrender, he told Frank Grouard, who in turn told Robert Strahorn, reporter for the Rocky Mountain News, that he, in fact, had two thousand warriors posted behind the crags of the cañon and would have swooped down on Crook had he dared to enter. “Another terrible massacre would have been the inevitable result,” Strahorn penned. Horned Horse told Chicago Times reporter Charles Diehl much the same thing at Camp Robinson on May 24, 1877, again during the time of the surrenders. Horned Horse had come in with Crazy Horse and told Diehl that the chief purposefully retreated with the idea that the troops would follow, and “then fall into their stronghold.” The peril of the Narrows is a notion that dogs the Rosebud story to this day.

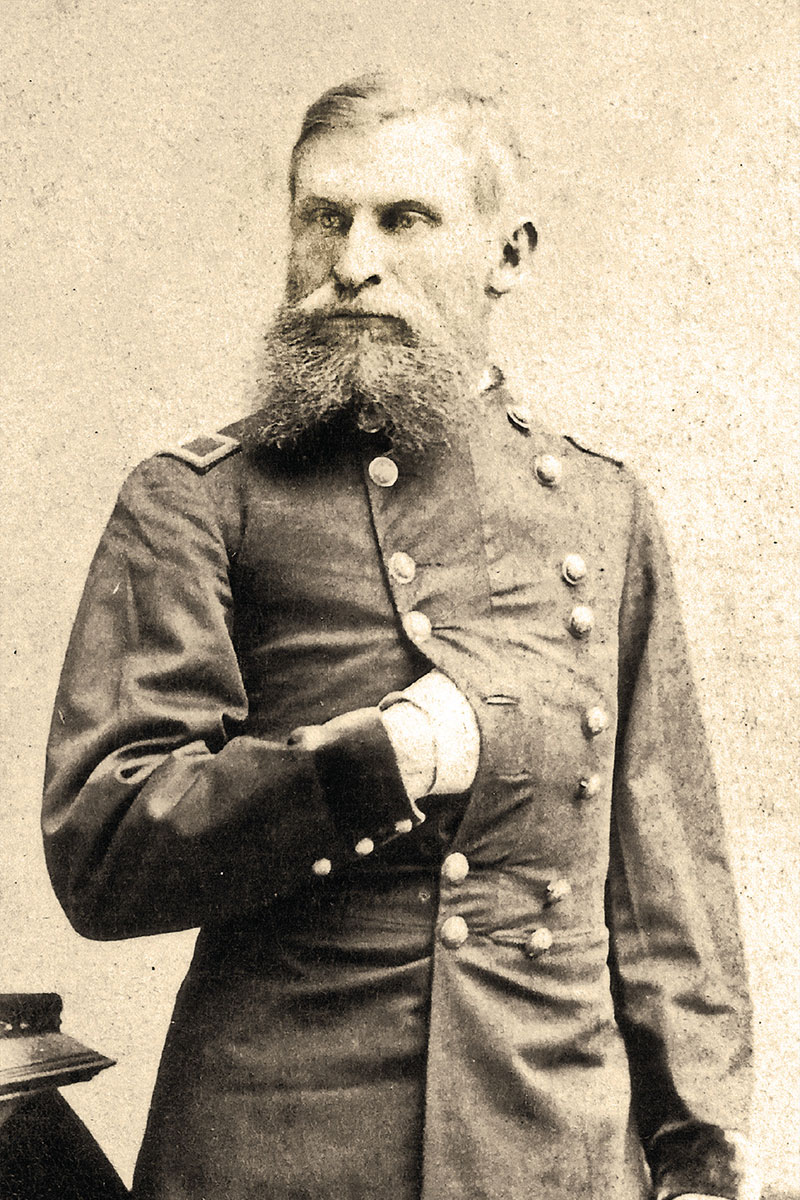

— Courtesy Paul M. Hedren —

Nothing of the sort happened, of course. Crazy Horse did not command two thousand warriors at the close of the battle or at any time, and no stronghold or trap existed in the cañon. He and some dozens of followers may have lingered on the heights of the Narrows to see whether Crook actually ventured that way, and perhaps would have renewed a fight of sorts. But Crook remained strong and capable, his cavalry bruised but cohesive and ably led. Sioux and Cheyenne warriors had been strong that day, as well, but by mid-afternoon they were hungry, tired, and making their way to their camps on Reno Creek.

That evening, Crook again implored his scouts to join him in an advance down the Rosebud under the cover of darkness for an attack on the village at daybreak the next morning. Again they demurred and stood by their reasoning. But suppose that the Crows and Shoshones had agreed to an advance down the stream, whether on the afternoon of June 17, or in the wee hours of June 18. Almost certainly Crook would have reengaged his enemy. On the afternoon of the 17th, Crazy Horse, based on the evidence gathered after his surrender, would have responded. It might have been a small fight that could well have escalated into a major battle had other warriors rallied to the chief’s side. In the mid-afternoon the entire Sioux and Cheyenne fighting force was within meaningful recall, even if dog tired and making their way to their Reno Creek camp. A second battle of the Rosebud might have played out that afternoon. In the cañon, Crook’s troops would have been at a distinct disadvantage in an escalating fight simply because the Indians would have spilled from the prevailing high ground. How long such a renewed fight might have ensued is pure conjecture, as is the outcome. It was the high ground that gave dominance to the position, not crags, fallen trees, or any other vestige of a so-called trap. But again, nothing of the sort happened. Crook did not advance down the Rosebud Narrows on the afternoon of June 17.

What if Crook had pursued his opponents on June 18? Until his scouts refused again to join him, Crook, having implored them for the second time on the evening of the 17th to do so, was fully prepared to reapportion his existing ammunition, which remained plentiful column-wide, park his wounded on the east-west reach of the Rosebud, likely in the care of Tom Moore’s packers and perhaps an infantry company or two, and advance down the stream. Crook’s Indian allies were crucial, both as trailers and as a fighting force, but the trail itself was obvious. Certainly such a movement would have been observed. A handful of warriors remained on the field through the evening of June 17 keeping an eye on Crook. But while any movement on Crook’s part in the wee hours of the next morning would have been seen, the general would have had the advantage. Aside from those few warriors stalking him, the considerable force that challenged him so heroically on the seventeenth were home and tending personal and family matters. Crook’s Crows and Shoshones would have followed the enormous pony trail down the Rosebud to where it diverted northwestward, out of the valley and straight to the Forks of Reno Creek. At that moment, Crook and his scouts would have quickly grasped that Sitting Bull’s village was not on Rosebud Creek at all but across the divide to the west. The point would have been wholly immaterial. Crook, the aggressor, would have followed the trail to that village, and in some likelihood would have reached and attacked it at dawn, the classic moment in which attacks on Indian villages optimally occurred.

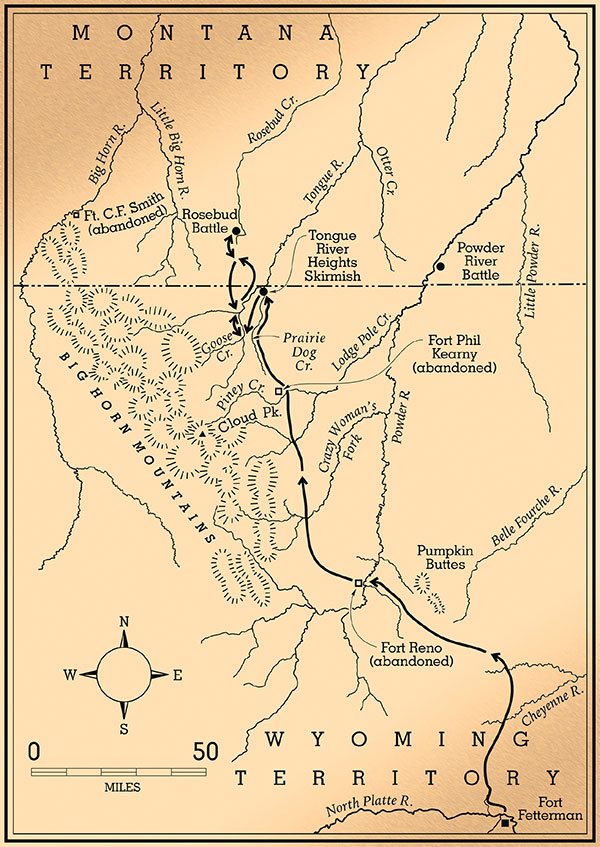

— Courtesy True West Archives —

If Crook had attacked Sitting Bull’s camp on the morning of June 18, his force was every bit the equal in count to the warriors occupying that sprawling camp. In a dawn attack, more or less a surprise assault, even if the four dogging warriors had somehow preceded him to the village and sounded an alarm, the advantage would not have fallen to the tribesmen but to General Crook. He would have been attacking a village filled with women, children, and the elderly. Mass chaos would have ensued. Crook certainly would have personally taken high ground, just as he did on the Camel-Back Ridge, and commanded another great battle, throwing all of his troops into the fight cohesively. In due course he would have been resisted—fiercely—but warrior allegiances, particularly in the confusion of the initial attack, would have been torn between aggressively countering the blow and the burdens of defending the defenseless. The advantage in such circumstances always accrued to the Army. Victory for Crook was not inevitable, but it may have been probable. The camp sprawled for miles, but this village was not yet the even larger Little Big Horn camp. Its defense would have been vigorous, the fighting bloody and devastating. And yet history suggests that Plains Indians never won village battles but instead fought and fled. Whitestone Hill, Killdeer Mountain, Sand Creek, Washita, even Powder River affirmed that fact, and the point was doctrine in the Army. But the point is also moot. Crook did not advance down the Rosebud in the dawning hours of June 18.

An aggressive movement on Crook’s part on June 17 or 18 would have had one other and perhaps even greater component effect on the larger story of the Great Sioux War. This was a village basking in the glow of the great Northern Indian Ascendency, Lakota and Northern Cheyenne people rallying to the cause of tribal sovereignty and sacred rights. They were headstrong, they were empowered by Sitting Bull’s Sun Dance vision, and they were growing numerically stronger by the day, even as they were equally vulnerable. Sitting Bull’s village overflowed with foodstuffs, day-to-day wares, cultural finery, and people, with five times as many non-combatants present as warriors. At Rosebud and Prairie Dog Creek, Sitting Bull’s warriors took the fight to the general. Here, Crook would have been taking the fight straight to Sitting Bull. Win, lose or draw, the disruption would have been catastrophic. In some likelihood, the village could not have remained cohesive. Conventional wisdom and simple fact suggest that villages under such duress scattered. Perhaps it would have regrouped, but perhaps not. Perhaps the great Ascendency might have regenerated, but perhaps not. The summer people may have continued their outward course from the agencies into the buffalo country, but perhaps not, especially now after another aggressive Army attack on a Northern Indian village, and this time no less than Sitting Bull’s village. But this disruption to the Ascendency never occurred. Crook did not advance down the Rosebud Narrows.

Allow Crook his withdrawal to Goose Creek to tend his wounded and resupply, and accept the abandonment of the Crows and Shoshones. The retrograde was completed on the afternoon of June 19. On June 20 attention turned to preparing for the retirement of the wagons and ambulances to Fort Fetterman on June 21. Certainly time was sufficient on the afternoon of the 19th, all of the 20th, and some or all of the 21st to fully reequip the expedition’s men with full issues of ammunition and rations. With this, Crook could have renewed the campaign immediately. While some stores still required caching on Goose Creek, Crook’s vaunted mule train could easily have been reconstituted to carry essential reserves of munitions, food and grain. Allow that two infantry companies were allotted to the departing wagon train, and maybe one more detailed to protect the stores on Goose Creek, there to join a greatly downsized cadre of lingering teamsters, packers, and miners. Crook still would have had all fifteen companies of his cavalry and two, maybe three companies of infantry. He could have renewed his offensive movement with upwards of 950 men, this time well supported by Moore’s pack train and commencing on June 21 after the departure of the wagons, or in the customary wee hours of the following day.

Crook’s trail north would have been simple. Even without Indian scouts, he knew the way to the Rosebud’s east-west reach and the Narrows, which he could have reached on the afternoon of June 23. He could have made his way partly through the Narrows late in the day or on the morning of June 24, and turned northwestward toward the Forks of Reno Creek following a still-obvious pony trail. He may have crossed paths with other bodies of Indians, summer roamers perhaps, or they with him. Fighting may have erupted. Then again, he may have discovered or himself been discovered by Custer’s Arikara and Crow scouts who on June 24 were ranging far ahead of that column as it too wended its way up Rosebud Creek while Crook was perchance ranging down that same stream. The notion of Crook and Custer operating in concert against an enemy whose trail, whether scored by travois tracks or pony tracks, “could have been followed by a blind person,” as Wooden Leg recalled, becomes yet another intriguing what-if of the Rosebud story. Even the cagey Hunkpapa warrior Rain in the Face appreciated the threat of a Crook-Custer alliance, telling an interviewer in 1905 that Crook might well have “pushed on and connected with the Long-Haired Chief. That would have saved Custer and perhaps won the day.” Henry Noyes of the Second Cavalry in Crook’s column saw it this way, as well, embracing the merits of supporting General Terry, commanding the Dakota column, at this early stage of the war. But, remembered Noyes, “we returned to our base on Goose Creek, and a week later heard of the massacre of General Custer’s party.”

The simple fact is that Crook did not renew his campaign after securing his wounded. He never rendezvoused with Custer. They never jointly swooped down on Sitting Bull’s village. It might well have been the battle that ended the war and conquered the Sioux. General Crook might have changed history. Instead, he went fishing.

This tale of “what if” is drawn from the concluding chapter of Paul Hedren’s latest book, Rosebud, June 17, 1876: Prelude to the Little Big Horn, published in April by the University of Oklahoma Press. Hedren, a retired National Park Service superintendent, resides in Omaha, Nebraska, where he tirelessly chases Crook, Crazy Horse and the Great Sioux War. As he says, someone must do so.