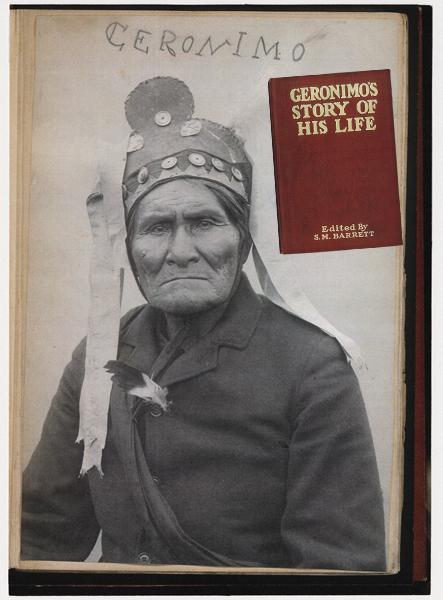

“It is my land, my home, my fathers’ land, to which I now ask to be allowed to return. I want to spend my last days there, and be buried among those mountains.”

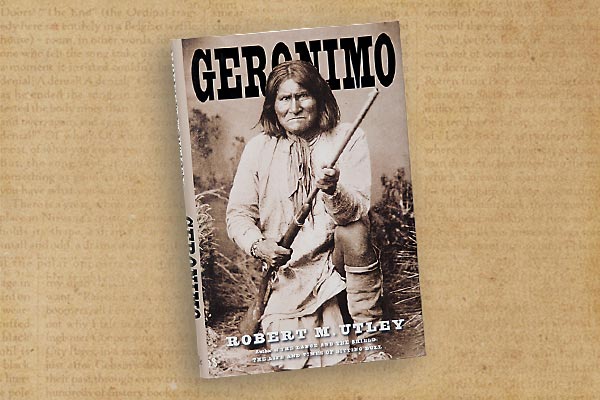

Geronimo’s mournful words published in his autobiography have touched off a furor spanning a century and thousands of miles, with a cast including his living relatives and the uppermost echelons of U.S. politics and society.

On the 100th anniversary of the Apache medicine man’s death in 2009, Harlyn Geronimo, of Mescalero, New Mexico, claiming to be a great-grandson, filed suit at the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. He wants to repatriate Geronimo to that rugged landscape of rolling hills and Ponderosa we now call the Gila Wilderness, just west of Silver City.

If no authoritative lineal descendant emerges, Geronimo will stay where he’s rested for the last century—buried in Oklahoma beneath a stone monument at Fort Sill, in the Apache Prisoner of War Cemetery.

Harlyn declined to comment for this story, but his friend Carlos Melendrez of Las Cruces says it’s time the government makes good on its pledge to free the Apache warrior.

In his autobiography Geronimo claimed he was promised eventual freedom as a condition of his surrender in 1886. Yet he remained a prisoner for the rest of his life, dying of pneumonia at Fort Sill in 1909.

“We’re just here to bring Geronimo home,” says Melendrez, adding the case is motivated by that “essential promise of freedom.”

The lawsuit cites the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, legislation created in 1990 requiring federal agencies to return artifacts and burial remains to their original tribes. In addition to Geronimo’s remains, the lawsuit calls for unspecified monetary damages.

Harlyn has named as defendants President Barack Obama, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and former Secretary of the Army Pete Geren—the men in charge of all things military, including that single grave at Fort Sill.

Harlyn wants all of his great-grandfather, so the suit also names Yale University and Skull and Bones, a fraternal society that’s operated on the Ivy League campus since 1832. The rumor goes that in 1918 society member Prescott Bush—father and grandfather of U.S. Presidents and fellow Bonesmen George H.W. and George W. Bush—removed from the grave Geronimo’s skull, two femurs and the Apache’s prized bit and saddle horn.

A spokesman for Yale denied the university has any remains, and noted Skull and Bones operates independently of the school.

Three months after Harlyn filed suit, two separate groups of his fellow Apache emerged to oppose him.

Lariat Geronimo, 40, of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, also claims to be a great-grandson. He opposes reburial because he says it’s more important that the grave stays undisturbed. “Once you’re in the ground that’s it. You got to move on,” Lariat says. “It’s more traditional.”

In May 2009 the court granted a motion to equally weigh Lariat’s position that the remains stay put.

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe filed a similar motion, which the court is now considering. Jeff Houser, chairman of the tribe, says all relatives must agree before the remains go anywhere. “Since the entire Geronimo family does not want the remains to be moved, we believe they should remain undisturbed,” Houser says.

Also threatening the suit is a motion the federal defense filed in June to dismiss the case, claiming the laws don’t apply to the remains at Fort Sill.

But for Ramsey Clark, the plaintiff’s attorney, the heart of the matter defies legalese. “It certainly has a heavy spiritual element,” Clark says. “It’s a combination of common human emotions, after being exiled by force, to want to return home.”

Clark, 83, a former U.S. attorney general under President Lyndon Johnson, has defended Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Miloševic, both tried for war crimes.

Perhaps Geronimo himself foresaw the events that would unfold a century later, stating in his autobiography:

“But we can do nothing in this matter ourselves—we must wait until those in authority choose to act.”

UPDATE: The week of July 28, 2010, Judge Richard Roberts dismissed both lawsuits. The case against the federal government was dropped because the plaintiffs failed to establish the government had waived its right not to be sued without its consent; the case against Yale and the Skull and Bones Society was dropped because the plaintiffs cited a law that only applies to American Indian artifacts excavated or discovered after 1990.

On August 11, 2010, the Las Cruces Sun-News reported that Harlyn Geronimo and the other plaintiffs have not given up their fight. Their lawyer Ramsey Clark said: “We’re committed to trying to return Geronimo’s remnants to the headwaters of the Gila, and there is new hope that we can find ways to do it. This judgment does not preclude other efforts.” Clark added, “We have asked the court for an order causing the exhumation of remains to determine that they are Geronimo’s and whether all the remains are there.”

Art Martori is a former newspaper reporter for the East Valley Tribune and Arizona Republic. He works as a freelance journalist and writes short fiction in his native Phoenix.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –