The Pathfinder’s 1843 expedition across the West is still a grand route for adventurous travelers.

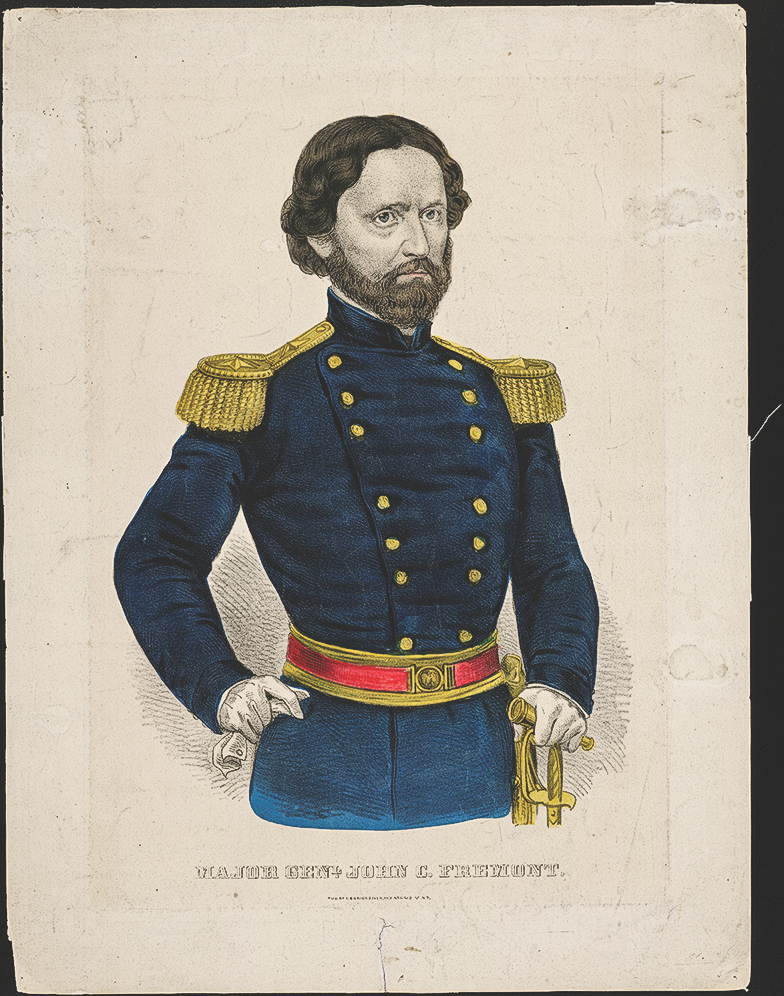

John C. Fremont, known as The Pathfinder, had a guide on every trip he made into the West. In 1842 Kit Carson led him west, and in 1843 Carson and Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick journeyed with Fremont. Carson and Fitzpatrick had long experience traveling in the West, earned during their years in the fur trade. The 1843 Fremont Expedition departed from St. Louis, crossing Kansas by following the Arkansas River to Bent’s Fort, an important trading post on the Santa Fe Trail that has been rebuilt and is now operating as a National Historic Site. From Bent’s Fort, present-day travelers should continue to Pueblo, Colorado, before turning north to the area of today’s Fort Collins, Colorado, and then travel north and west to the Medicine Bow Mountains of southern Wyoming.

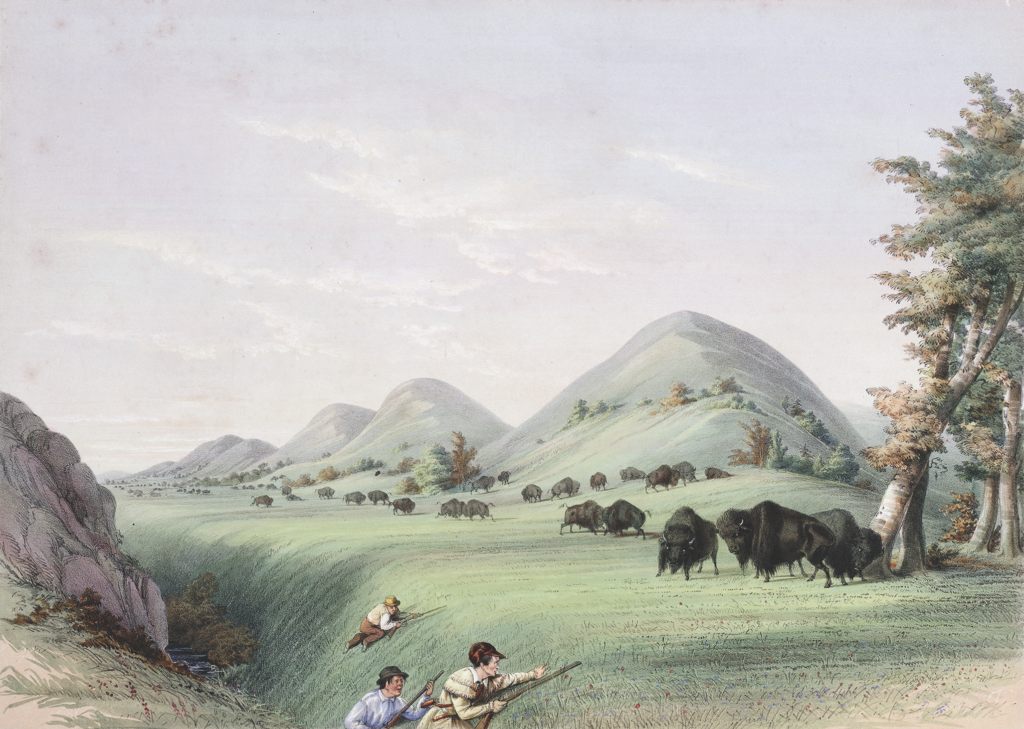

Fremont’s exploration allowed members of his parties to collect plant specimens, make topographical sketches and undertake other scientific study. In early August of 1843, Fremont was in Carbon County, Wyoming, traveling west and camping on the principal fork of the Medicine Bow River near “an isolated mountain called the Medicine Butte” known today as Elk Mountain. On August 3, 1843, Fremont’s group saw “bands of buffalo,” and that evening Kit Carson “brought into the camp a cow which had the fat on the fleece two inches thick.” Fremont wrote that this “was the first good buffalo meat we had obtained.” Learn more about this region at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins.

Fremont camped at the North Platte River, where Fort Steele would eventually be built, and his men were drying the buffalo meat when they were “thrown into sudden tumult, by a charge from about 70 mounted Indians,” who had come over the low hills. The attack ended abruptly when the charging Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians saw the small cannon Fremont had with him. Fremont later wrote the “display of our little howitzer, and our favorable position in the grove certainly saved our horses, and probably ourselves, from their marauding intentions.”

From their campsite near the North Platte, Fremont’s party turned north through Muddy Gap to the Sweetwater River, which they followed over South Pass taking “the road to Oregon.”

Now on the trail that Indians and mountain men had used for decades, Fremont traveled though the Green River Valley to Bear River, and then turned south to the Great Salt Lake, where he collected plants and rocks as he explored the “waters of the inland sea, stretching in still and solitary grandeur far beyond the limit of our vision.”

Jim Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez started a trading post in 1842 in the lower Green River Valley, at a place Bridger knew overland travelers would visit. He was well acquainted with the region of southwest Wyoming, having trapped and traded there for nearly 20 years. The location of his post is now the site of Fort Bridger State Historic Site, which hosts one of the largest mountain man rendezvous in the Rocky Mountains each year over Labor Day Weekend.

The Great Salt Lake had been seen by trappers—Bridger saw it in 1825—who wandered through the country in search of new beaver streams. But Fremont noted they cared little about the geography, and islands in the lake had not been explored by any American expedition, so that became one of his objectives. “It was generally supposed that it had no visible outlet; but among trappers, including those in my own camp, were many who believed that somewhere on its surface was a terrible whirlpool, through which its waters found their way to the ocean by some subterranean communication. All these things had made a frequent subject of discussion in our desultory conversations around the fires at night; and my own mind had become tolerably well filled with their indefinite pictures, and insensibly colored with their romantic descriptions, which, in the pleasure of excitement, I was well disposed to believe. And half expected to realize.”

Fremont spent nearly a month exploring the Great Salt Lake, its islands and the general area before his party headed north, reuniting with Fitzpatrick at the Hudson’s Bay Company post of Fort Hall in eastern Idaho. A recreation of this post is in Pocatello, Idaho. Fitzpatrick then took Fremont west following the Snake River toward Fort Boise on an ill-defined trail that was just beginning to see the great influx of travelers headed to Oregon Country. The Oregon Trail later became the first major emigrant route across the West, in use until the late 1860s by families who loaded their wagons with household goods, food, farm implements, supplies and kids and set out to claim land in Oregon.

At the Grande Ronde River in northeast Oregon near La Grande, Fremont began following an Indian trail to find a “more direct and better road across the Blue mountains.” He reached the Whitman Mission on October 24 and soon saw the Columbia River, which he followed along the south bank to The Dalles, where he took a canoe to float down the Columbia to Fort Vancouver (which was just north of the river). Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin, manager at Fort Vancouver, supplied Fremont with provisions so he could continue his travels. Fremont returned to The Dalles then traveled south through the Tygh Valley and around Klamath Lake before continuing into California.

Traversing northern California and the Sierra Nevada in the winter challenged the expedition, but in March 1844 they reached Sutter’s Fort, which can still be visited in Sacramento, California. After a time to recuperate from their survey, Fremont’s party journeyed south into the San Joaquin Valley. There Fremont met the Old Spanish Trail—a route that linked southern California with Santa Fe. He followed that trail northeast into the Great Basin, striking the Virgin River and entering the area of St. George, Utah, by early May 1844.

There Fremont found “an extensive meadow, rich in bunch grass, and fresh with numerous springs of clear water, all refreshing and delightful to look upon.” Fremont said this “was a very suitable place to recover from the fatigue and exhaustion of a month’s suffering in the hot and sterile desert. The meadow was about a mile wide, and some ten miles long, bordered by grassy hills and mountains.”

This meadow where Fremont found respite, became the site of an atrocious attack on a wagon train in September 1857, when Mormons surrounded and eventually murdered 119 wagon train travelers from Arkansas in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, allowing only some children to survive, believing they were too young to remember the siege and subsequent killing of their families.

The Fremont Expedition continued along the Old Spanish Trail route to Brown’s Park, Colorado, and then swung north. On June 11, 1844, Fremont was back in Carbon County, Wyoming, traveling into the Little Snake River Valley. He described the country as “sandy and poor, scantily wooded with cedars, but the river bottoms afforded good pasture.” The men killed three antelope in the afternoon and camped downstream from the point where Henry Fraeb had engaged in a fight with Indians three years earlier. This was the site of the fight along the Little Snake River with the Arapaho and Lakota Indians that gave Battle Mountain and Battle Pass their names. You can learn more about this fighting during a visit to the Little Snake River Valley Museum in Savery.

On June 13, 1844, Fremont moved deeper into the Sierra Madre range crossing the Continental Divide at midday where he noted, “With joy and exultation we saw ourselves once more on the top of the Rocky mountains, and beheld a little stream taking its course towards the rising sun.” Wyoming Highway 70, open from late May to mid-October, crosses the Sierra Madre from Savery to Encampment and keeps today’s adventurers relatively close to Fremont’s route.

Once on the east face of the Sierra Madre, Fremont turned south toward “objects worthy to be explored,” namely the North, Middle and South parks of Colorado. His route took him near today’s towns of Walden, Kremmling, Leadville and Buena Vista. His party again began following the Arkansas River, this time headed downstream through Pueblo, and once again to Bent’s Fort, where he picked up the Santa Fe Trail, which took him back east, reaching St. Louis on August 6, 1844, and concluding a 14-month reconnaissance of the West.

Candy Moulton, recipient of the 2023 True Westerner Award, is a road warrior and writer. Her newest book, Sacajawea: Mystery, Myth and Legend, is forthcoming in June from the South Dakota Historical Society Press.

A Wide Spot in the Road

South Pass City

State Historical Site

Fremont’s expedition in 1842 penetrated the Wind River Mountain Range where in mid-August Fremont along with Charles Preuss and Johnny Janisse climbed the highest peak in Wyoming. They named it Fremont Peak. The explorer didn’t return to that site on his 1843 journey, but he did cross South Pass, as would hundreds of thousands of people who followed the Oregon, California, Mormon and Pony Express Trails. Some of those travelers noted the presence of gold in the South Pass region, later returning to begin explorations and successfully finding gold in 1866. This led to the establishment of South Pass City, which became an important economic and political site when Wyoming Territory was established in 1868. It was here that woman suffrage got its start in the West, thanks to the efforts of Esther Hobart Morris and men who lived in the boomtown. SouthPassCity.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Elk Mountain Hotel, Elk Mountain, WY; Hotel Wolf, Saratoga, WY; Su Casa, Sinclair, WY; The Red Iguana, Salt Lake City, UT; Cousins, The Dalles, OR; Carol’s Corner Café, Vancouver, WA; Café Bernardo, Sacramento, CA

Good Lodging: Kimpton Hotel Monaco, Salt Lake City, UT; Hotel 43, Boise, ID; The Heathman Lodge, Vancouver, WA; Spirit West River Lodge, Riverside, WY; Antlers Inn, Walden, CO