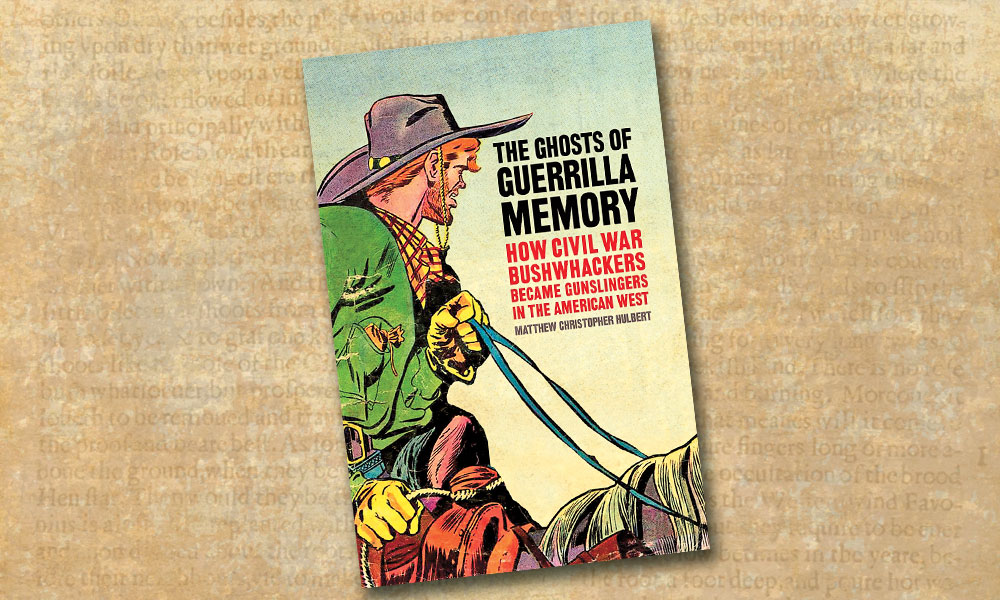

A century and a half after the Civil War, the romance and reality of Western outlaw history remains a favorite subject of historians, re-enactors, media mythmakers, museums and historical societies. Matthew Christopher Hulbert’s The Ghosts of Guerilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West (University of Georgia Press, $84.95/$29.95), is a groundbreaking interdisciplinary history of the rise of American guerilla warfare in the Missouri-Kansas conflict in the years leading up to President Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860, and the role of guerilla fighters and bushwhackers throughout the War Between the States. Hulbert, a lecturer in the Texas A&M University-Kingsville Department of History, Political Science and Philosophy, does not trap his research and conclusions in the 19th century, but pursues conclusions to his thesis from a 21st-century perspective. He writes: “How did the relegation of the most infamous guerrillas to the realm of western pop culture affect guerrilla memory as a whole? Why do Americans seem more comfortable with ex-bushwhackers as gunslingers and cowboys and bank robbers than as participants in the war that saved the Union and emancipated millions of African American slaves?”

These are ambitious questions for a young historian to pursue in his first major synthesis, yet Hulbert’s detailed and thoughtful research across numerous disciplines, genres and mediums, and his passionate interest in post-Civil War outlawry, provide new perspective on the role of mythmakers in our shared collective memory of Civil War guerrillas—as heroes and antiheroes in the real and imagined Wild West. As Hulbert writes, “To many of the men, women and children in Missouri and Kansas who took in and fought the Civil War from their porch steps, the guerrilla war and its aftermath represented the status quo as they knew it—and neither the signatures of Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston, nor the efforts of later partisan propagandists, could wipe clean such a backlog of intensely personal violence.”

Writers, researchers and historians of Western history should read Hulbert’s well-researched and thought-provoking public history study of America’s most-misunderstood war within a war—and how those border warriors, guerrilla soldiers and lawless bushwhackers became the storied, legendary outlaws of our Old West panoply. His conclusions of who these guerrillas really were, and how they fought, raped, maimed, murdered and killed may be shocking and in direct conflict with how our modern mythmakers have interpreted them through pulp fiction, literature, film and television. But in the end, without asking the questions and providing revealing answers, how can we resolve our ongoing conflicting conclusions about who fought the Civil War, and who continued to fight beyond the boundaries of law and order for decades after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse?

As Hulbert succinctly states in his conclusion of The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory, “I hope this story of guerrilla memory—and of the scars it left, and of those it failed to leave—on the physical landscape of the guerilla theater illuminate that the margins of Civil War history, however unseemly their violence or irregular their recollections, are worth accounting for…because one never knows when the fringes of one narrative will become the centerpiece of another.”

—Stuart Rosebrook