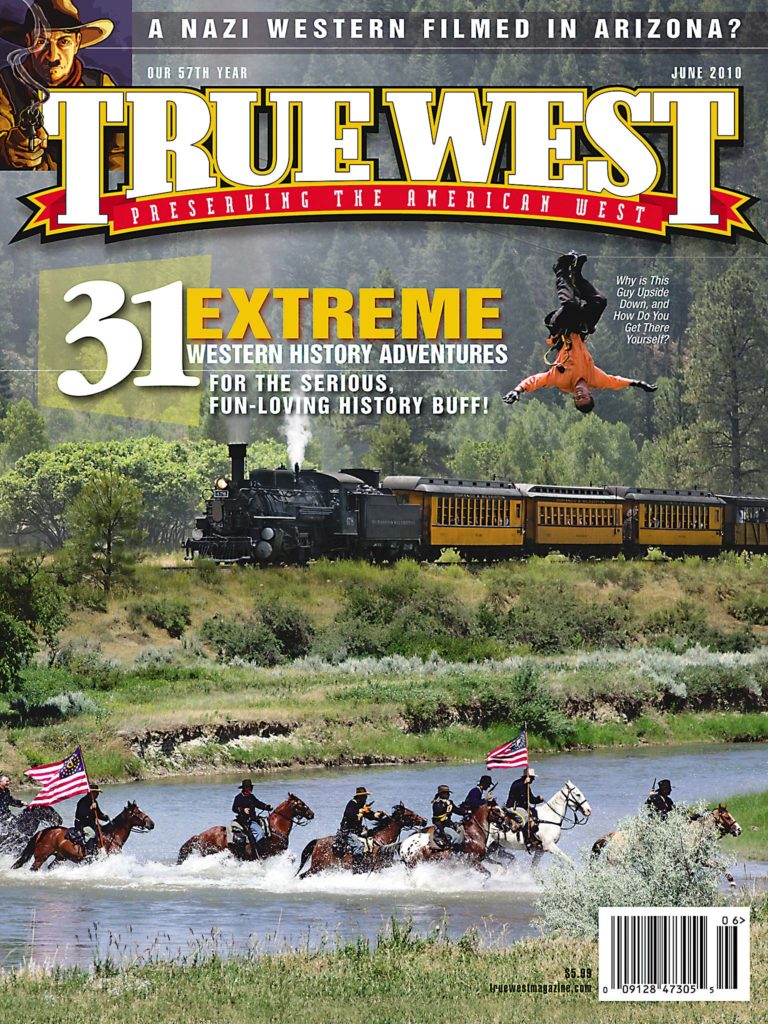

For those of you who may have wondered what book laid on the reading table next to Adolph Hitler’s bed, you might be surprised to learn it was likely a Western.

For those of you who may have wondered what book laid on the reading table next to Adolph Hitler’s bed, you might be surprised to learn it was likely a Western.

In his 1976 prison memoir Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Minister of Armaments and War Production for the Third Reich Albert Speer recorded: “Hitler was wont to say that he had always been deeply impressed by the tactical finesse and circumspection that Karl May conferred upon his character Winnetou…. And he would add that during his reading hours at night, when faced with seemingly hopeless situations, he would still reach for those stories, that they gave him courage like works of philosophy for others or the Bible for elderly people.”

On January 18, 1933, Hitler and Dr. Paul Joseph Goebbels saw a movie that had premiered in Berlin just the day before, Der Rebell, starring Luis Trenker.

Twelve days later, Hitler became chancellor of Germany. The only Nazi Western filmed in America would begin shooting two and a half years later.

The swastika once flew over the American West. Well into the early 20th century, the flag of the U.S. Reclamation Service (renamed the Bureau of Reclamation in 1923) had a swastika as part of its design because the “whirling winds” shape represented life and good luck to many southwestern American Indian tribes.

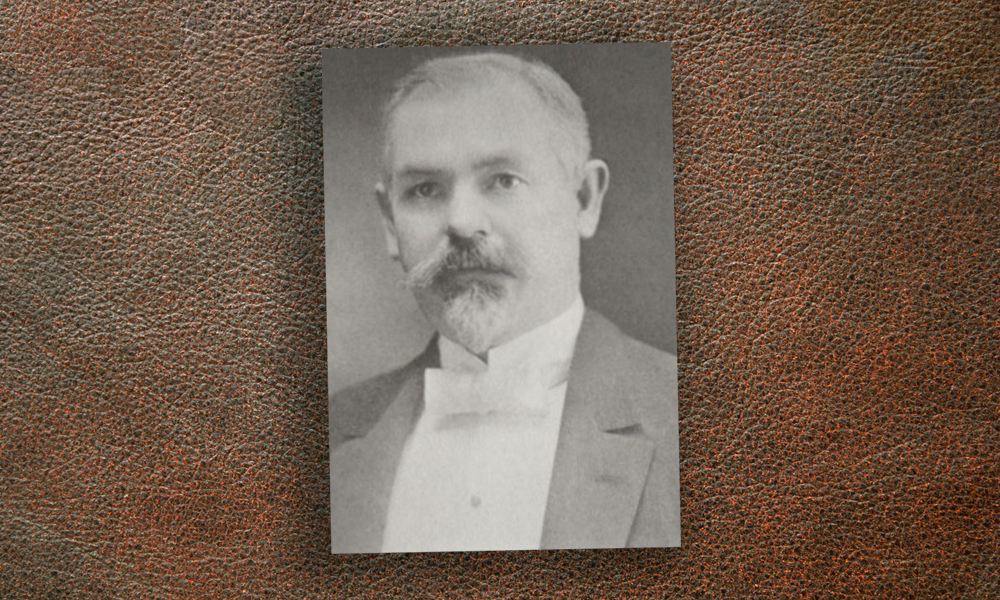

In Karl May’s Winnetou novels, an illustrator incorporated this swastika symbol; some historians suspect May’s books might be where a young Adolf Hitler first became fascinated with the swastika. May (1842–1912) is the most popular author in German history, and his adventures of the fictional Mescalero Apache chief Winnetou and his Teutonic companion Old Shatterhand in the Wild West remain the German-speaking world’s biggest-selling series of novels.

Hitler often quoted May in his speeches, and he had 300,000 copies of May’s novels distributed to Nazi troops during the war; on June 26, 1944, a Berlin newspaper reported that large numbers of German soldiers were grateful to Karl May—who, ironically, was a pacifist—for providing them with the “best manuals of anti-partisan warfare.”

Although Western movies were made in Germany during the silent era—long before he flapped his wings as Dracula, Hungarian-born Bela Lugosi played an American Indian in a pair of 1920 James Fenimore Cooper adaptations, Der Wildtöter und Chingachgook (The Deerslayer and Chingachgook) and Der Letzte der Mohikaner (The Last of the Mohicans)—none of the Winnetou and Old Shatterhand tales reached the screen until 1962.

Even so, May’s peculiarly Teutonic vision of the West exerted a strong influence on Der Kaiser von Kalifornien (The Emperor of California), a 1936 anti-capitalist propaganda diatribe about the rise and fall of German immigrant Johann Augustus Suter that was the first Nazi Western film.

Suter (Americanized as John Sutter) was an ambitious German-born Swiss trader and farmer who became famous because of the 1848 discovery of gold on his property at Sutter’s Mill in California, which inspired the Gold Rush. Squatters would overrun his property, and Suter eventually went bankrupt, dying nearly penniless in 1880.

The historical Suter (as John Sutter) made his first appearance on film in 1924, depicted as, of all things, an action hero, in Days of ’49, a silent 15-chapter serial released by the Arrow Film Corporation. By 1934, Universal had Howard Hawks set to direct an epic version of Suter’s life based on a treatment written by Nobel Prize–winning novelist William Faulkner. Yet Hawks walked off the project after growing frustrated by Universal’s budget restrictions. Universal would still make the film, under director James Cruze, calling it Sutter’s Gold.

The Nazi Western Kaiser was written, produced and directed by Luis Trenker, who also starred as Suter. Trenker had made his mark as a leading man in Bergfilm (mountain film), the man-versus-nature adventure genre popular in Germany’s pre-Hitler Weimar Republic, but he is a forgotten figure of film history today, especially in America.

“The mountain film was to Germany what the Western was to America,” wrote respected film historian William K. Everson in 1984’s Films in Review, “and Trenker, as its leading practitioner, was in a sense Germany’s John Wayne and John Ford rolled into one.”

Nazis in Hollywood

Incredibly, some of Kaiser’s outdoor scenes were actually shot on location in the United States, and in the film, Sedona, Arizona, is Suter’s Valhalla.

The cash to shoot in America came from outside Germany, from a Tobis subsidiary based in Holland, Tobis Maatschappij Amsterdam. What Trenker always failed to mention was that in February 1935, Tobis Amsterdam’s parent company, Internationale Tobis NV (or Intertobis), was secretly purchased by the Nazi front company Cautio GmbH as part of the Reich’s covert plan to seize control of the German film industry; by 1939, the Nazis would have absolute authority over every division of Tobis in Europe.

After Trenker and his crew arrived in America, the Germans headed west by train. Their landing in Hollywood made Variety’s front page on August 7, 1935: “Nazis in Hollywood on Kaiser Location.”

Kaiser filming apparently started in California. Trenker wrote of working near Mount Whitney in Alles gut gegangen; that’s confirmed by a few quick shots photographed in Lone Pine’s easily recognizable Alabama Hills. In one sequence, he rides a horse through the boulder-strewn pass that would soon become

B-western hallowed ground: the “Lone Ranger Ambush Site” of Republic Pictures’ 1938 serial The Lone Ranger. More filming definitely took place in nearby Death Valley.

Trenker distinctly remembered renting a stallion named Sheik from a Kernville, California, rancher for the duration of Kaiser’s shoot. Sheik was used often in low-budget Westerns, ridden by the likes of John Wayne, William Boyd and Tim McCoy, and he would later face off against Rex in the filmed-in-Sedona King of the Sierras. Because Sheik was distinctively marked by heavy mottling on his face, it’s easy to spot him in at least two Kaiser sequences: the trek through California’s Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area and in one of the scenes filmed in Sedona, where he’s ridden by actor Reinhold Pasch.

Trenker purchased a secondhand Packard automobile and three used Chrysler limousines in California for the company to drive to Arizona, where they took rooms in the El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. German audiences expected mountain climbing in Trenker’s films, and in Kaiser he obliged spectacularly by scaling the walls and rocks of the Grand Canyon during Suter’s quest for California. The long climb climaxes when, through the magic of creative editing, he reaches the top of the canyon only to be overwhelmed by the panoramic view of California—actually Sedona—spread out before him, excitedly exclaiming “California! Hello!” at the breathtaking vision.

This is an unnerving sequence, and not just because of the dizzyingly high views and mixed-up geography. As British arts and culture historian Sir Christopher Frayling pointed out in his book Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone, the music heard during Trenker’s ascent of the Grand Canyon and subsequent descent of Schnebly Hill into Sedona is an eerie mix of the Nazi party anthem “Horst-Wessel-Lied” and America’s national anthem “The Star Spangled Banner.”

On September 11, 1935, Trenker, his wife Hilde, cinematographer Albert Benitz and other crew members arrived at Foxboro Ranches in Sedona. Sedona sequences were staged at what is now State Route 89A (near the foot of today’s Airport Road), the banks of Oak Creek, Munds Mountain Trail, Schnebly Hill and high atop the Mogollon Rim overlooking Little Horse Park.

As was the usual procedure for European films, the scenes photographed in Sedona were shot without sound. The German-language dialogue (“Look at the soil,” Trenker says in one scene, as the red dirt of Schnebly Hill slowly runs through his fingers; “it is like bread”) was looped in later during post-production.

Sedona looks exceptionally beautiful in Kaiser and has more screen time than in some better-remembered Westerns, like 1949’s Hellfire (starring “Wild Bill” Elliott) and 1968’s Firecreek (starring James Stewart and Henry Fonda). Albert Benitz’s low-angled photography of crisp skies and billowing white clouds seductively shadowing the peaks of the area’s massive rock formations provides some of the most heroic (and fascist) images of Sedona ever projected on a movie screen, visuals closer in style to the 1935 Hitler documentary Triumph of the Will than 1931’s Riders of the Purple Sage, shot in Sedona.

Trenker’s group spent three days at Foxboro before heading to Yuma, on September 13, where desert scenes were shot in the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area on the California border.

Before sailing back to Germany, the Kaiser company made a brief detour to Washington, D.C. to film the master shot of the elderly, almost penniless Suter slumped on the steps of the U.S. Capitol for the film’s climactic scene.

Shortly after arriving back in Berlin, Trenker reiterated Kaiser’s theme of Lebensraum to a German reporter, making it clear that he intended Kaiser to “capture the expansiveness of the world. We need the world. We are a people without a space, and it is the most important project of our future that we can solve and carry out this problem.. . . Is it not providence that this first real colonizer of California was a German?”

Due to budget cuts and the bitterly cold winters in Germany, most of Kaiser was shot in Italy.

Move Aside, Mr. Deeds

Der Kaiser von Kalifornien had its world premiere in Berlin on July 21, 1936, at a gala held at the Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda to honor Bernardo Attolico, fascist Italy’s newly appointed ambassador to Germany. Hitler and a rogues’s gallery of Nazi hierarchy were in attendance, including Goebbels, Reichsführer of the SS Heinrich Himmler and Reich Minister Ambassador-Plenipotentiary at Large Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Kaiser was awarded the Coppa Mussolini (Mussolini Cup), the top prize for best foreign film, at the Venice International Film Festival in 1936. Frank Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was also nominated in the best foreign film category in 1936; although it lost to Kaiser, it did win an award of “Special Recommendation.”

Hard as it is to believe today, the Third Reich repeatedly topped the list for the number of foreign films released in the U.S. during the 1930s. Sixty-nine of 216 imported films in 1937 originated in Germany, including Der Kaiser von Kalifornien, which had its American premiere on May 7 at New York City’s Casino Theatre.

The New York Times’s critic Harry T. Smith was surprisingly enthusiastic after he caught a screening at the Casino, declaring it “justifies the belief of many film patrons that semi-historical pictures can be interesting and entertaining without apocryphal heroines and phony comedians.”

But when the film opened in Great Britain in mid-1938 (a year before England and France declared war on Germany), critic A.V. of Monthly Film Bulletin raised a warning flag, pointing out that “one may note in passing that whereas Suter and his chief henchman (who gives his life for him) have Teutonic names, the villains of the piece (and they are villains indeed) have English names.”

Kaiser’s reviews were generally far more favorable than the ones garnered by Sutter’s Gold, which finally premiered in late March 1936. Time panned Gold as “eighty-five minutes of dignified boredom.” Gold reportedly cost $2 million to produce and was Universal’s biggest box-office flop of the era.

More Westerns were produced in Germany during the Third Reich, including Wasser für Canitoga (Water for Canitoga, which, despite having a character named Old Shatterhand, is not based on a story by Karl May), Sergeant Berry and Gold in New Frisco, directed by Paul Verhoeven, the actor who played Billy in Kaiser; all three films were made completely in Europe and released in 1939. After Kaiser, no other Nazi features were photographed on location in the United States.

Kaiser was one of the few Nazi films shown extensively in pre–WWII France. In Germany, it was designated one of the “Great National Films” revived to boost morale after Hitler ordered creation of the Volkssturm (people’s storm) militia of old men and teenage boys in September 1944 in a last-ditch attempt

to hold off the advancing Russian army. Despite the almost total destruction of Germany during the war, Kaiser exists today in almost pristine condition, in far better shape than almost every other film made in Sedona before it. With the ban on public exhibition lifted long ago, it is readily available on home video in Germany.

Trenker’s Epitaph

After 1945, Trenker always denied accusations that he was an opportunistic fellow traveler who embraced Nazism, and instead portrayed himself as a victim of political persecution. “I never paid much mind to politics,” insisted Trenker, always saying the Nazis used him for their own diabolical means before suppressing him and his work when they were no longer useful to them.

Trenker relocated to Rome before the war ended. In 1947 he made scandalous headlines around the world when he sold a diary attributed to Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun, to a German book publisher. His former costar and lover Leni Riefenstahl (whom the diary said danced nude for Hitler’s pleasure) claimed libel and joined with Braun’s family to win an injunction against the publisher to halt publication. Trenker, who was suspected of forging the diary himself, remained in Italy, safely out of reach of German criminal prosecution, adding yet another incident rarely mentioned by his defenders in accounts of his life.

Trenker returned to his homeland of South Tyrol (which stayed a part of Italy after the war) in 1949 to write and direct short films about the mountains and their inhabitants for his Munich-based production company. Within a few years, he was publicly rehabilitated as a beloved, white-haired, pipe-smoking grandfather figure who appeared regularly in films and on German and Austrian television.

In 1983, the Federal Republic of Germany’s Goethe-Institut sent him to the U.S. with prints of Der verlorene Sohn (a film he had starred in) and Der Kaiser von Kalifornien as part of a series of events celebrating the German immigrant experience in America. The tour culminated with an enthusiastic tribute held in his honor at the 10th annual Telluride Film Festival in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. It would not be until after his death in 1990 at age 97 and the reunification of Germany that a membership card discovered in his file at the Berlin Document Center would prove he’d joined the Nazi party in 1940. “I made my pictures a little with the brain and much with the heart,” Luis Trenker told the audience at Telluride in 1983, and perhaps it is this confession that should stand as his true, ignominious epitaph.

This edited excerpt is a preview of Arizona’s Little Hollywood: Sedona and Northern Arizona’s Forgotten Film History, 1923-1973 by Joe McNeill. You can purchase your copy at ArizonasLittleHollywood.com, where you can also watch a film clip from Der Kaiser von Kalifornien.