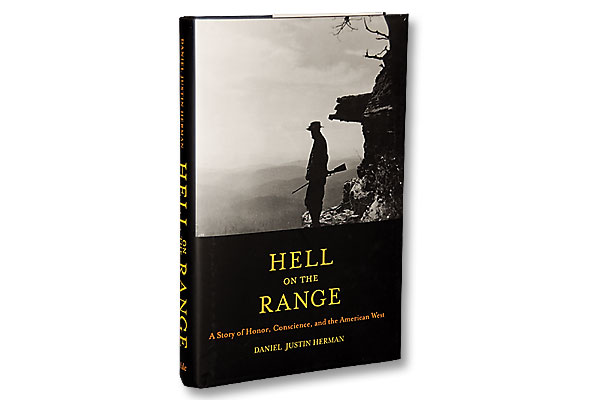

Life on the buffalo range was hard, dangerous work, often accomplished in extreme heat or freezing conditions, sometimes under the watchful eye of hostile Indians, who waited for a chance to put you out of business—for keeps! As part of a verse of the old frontier song titled “The Buffalo Skinners” goes, “While skinning the damned old stinkers our lives wasn’t a show, for the Indians watched to pick us off while skinning the buffalo.”

In order to perform their tasks more efficiently and economically, and to realize the most profit from the hides, meat and tongues of the great beasts slaughtered, market hunters adopted a number of unique methods while on the range.

In the age before modern safety procedures that today’s outdoorsmen take for granted—like hearing protection—many shooters went deaf from shooting their own guns, since they often fired hundreds, if not thousands, of rounds in a single season.

Professionals avoided shooting from the prone position. They felt the shock wave from firing traveled further across the ground, spooking the bison. Most hunters fired from a kneeling or sitting position, using a cross-stick rest for their heavy rifles, which averaged about 9 to 12 pounds, but could weigh as much as 17 pounds or more.

To further insure that an accurate shot was made, many hunters, who’s hands became calloused from living a rugged, outdoor life, would sandpaper or file down the skin on the tip of their trigger fingers, almost to the point of bleeding. This ensured that when the rifle’s “set trigger” was set into readiness for firing, their finger would be sensitive to the lightest touch required to discharge it.

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –

When venturing from their campsite for a day’s shooting, the wise hunters carried a canteen, possibly some jerked meat, perhaps a sidearm, a hunting knife and ammunition. Whatever the amount carried, generally about 40 to 60 rounds, a savvy hide man always kept ten rounds in reserve, in the event that Indians attacked him. With those reserve cartridges he could slowly retreat to his campsite, while keeping out of range of his pursuers’ bow and arrows or smaller-caliber rifles. The observant hunter also tried to stay in open country and never ventured too far into a group of animals, or allow the rummaging bison to surround him, for more than one overzealous buffalo man lost his scalp to Indians hiding in the midst of the herd.

The daily amount of animals killed by a hunter depended on the number of animals his skinners could strip of their hides and butcher during that same day, especially in extreme weather. In the frigid winter, it was an extremely difficult task to remove the hide after the carcass had frozen stiff, and in the sweltering summers, the downed buffs would spoil quickly.

When water was scarce, hunters carefully urinated down their rifle barrels to wash out the black powder carbon buildup, while cooling the barrel. Hunters sometimes carried a couple of guns. Despite the misconception that most of the meat was left to rot, these men also profited from the sale of this provender. Salable meat was either pickled in brine or smoked before hauling it to market. However, with no way of preserving what they harvested for themselves in hot weather, they sometimes seasoned the meat with black powder to disguise the rancid flavor.

Buffalo hunting was anything but romantic, yet despite the rugged conditions and constant dangers endured by these hunters, this grueling occupation continues to capture the fancy of legions of Old West buffs. Nonetheless, as another line of “The Buffalo Skinners” ditty reveals, “I’ll tell you there’s no worse hell on earth than the range of the buffalo.”