– All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted. –

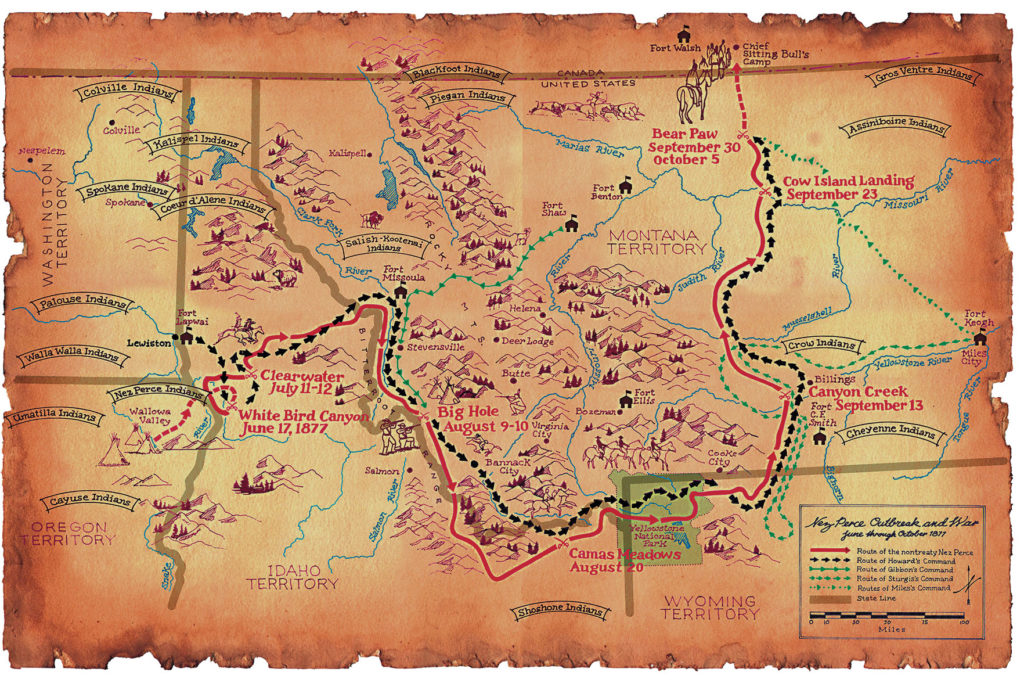

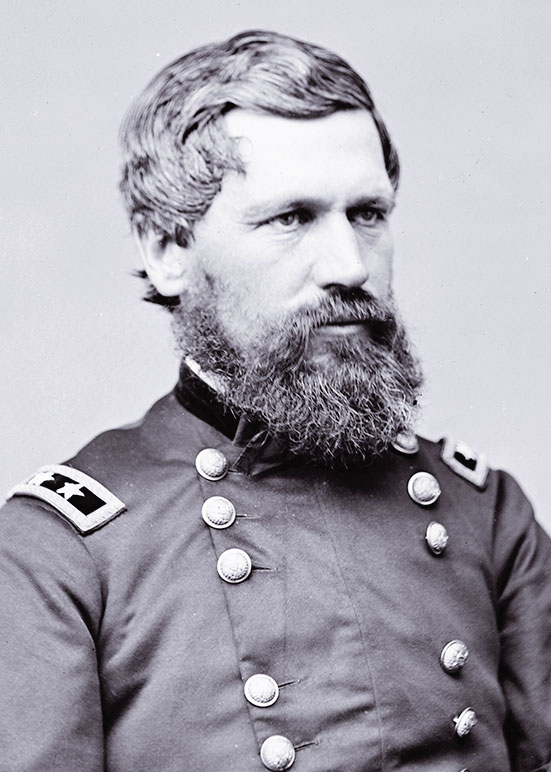

Fighting that broke out at White Bird Canyon in Idaho in June of 1877 between the Nez Perce Indians and the U.S. Army commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, had continued through the summer with engagements along the Clearwater River and at Camas Meadows in Idaho, and the Big Hole in western Montana. By August, the Nez Perce people had outpaced the Army as they struck the Madison River and followed it into Yellowstone National Park.

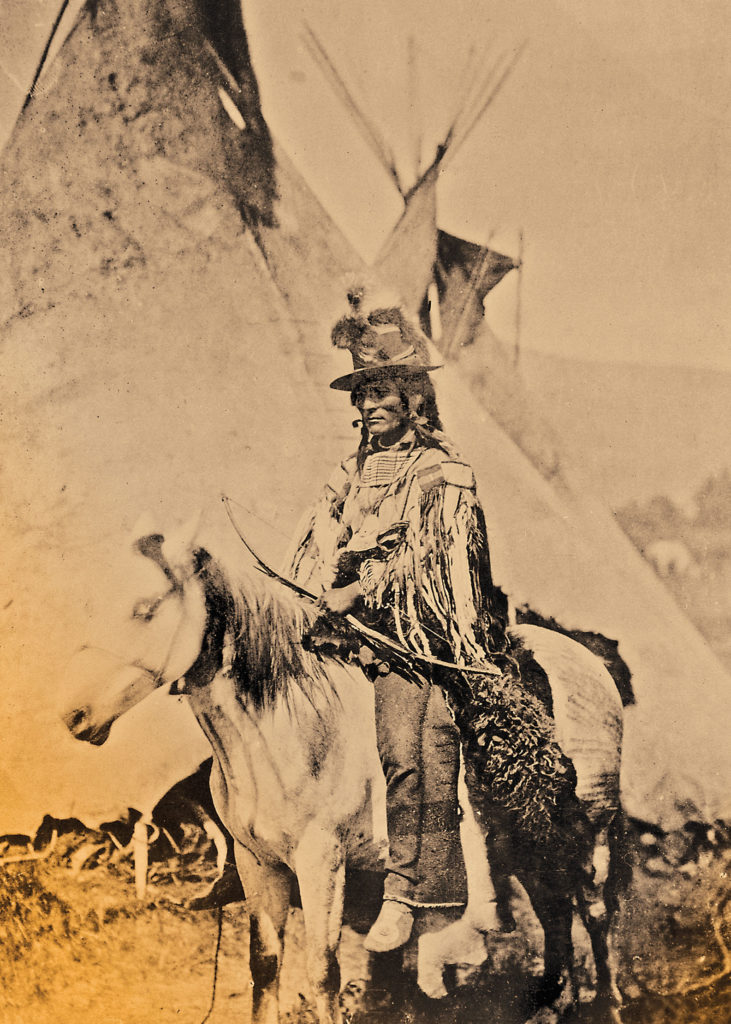

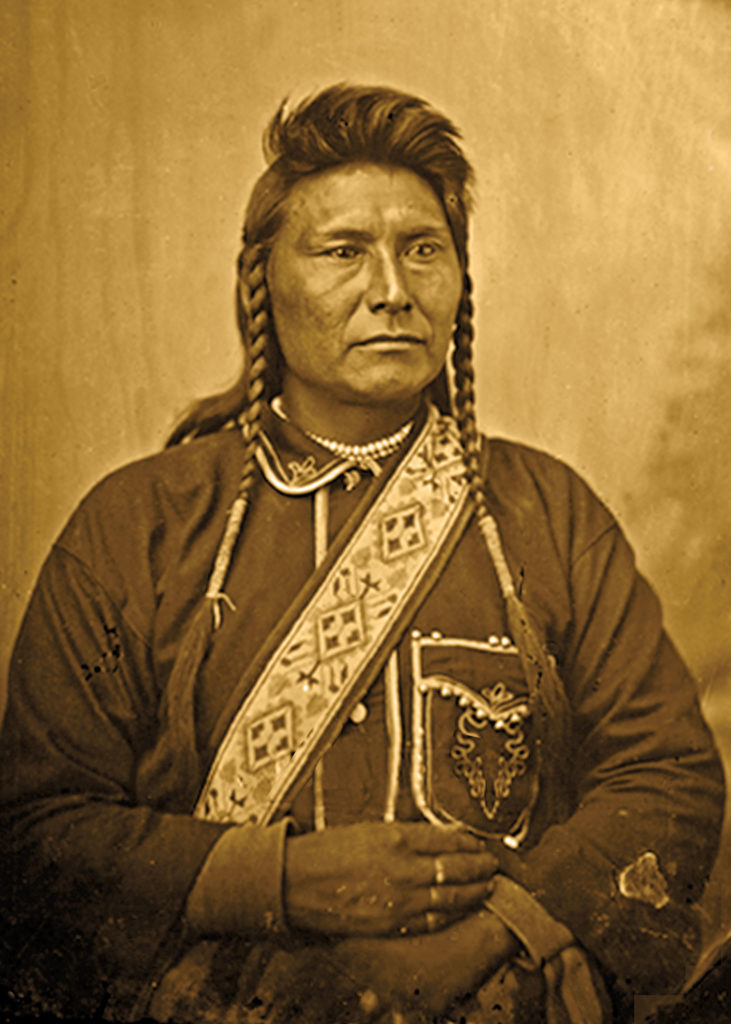

Few expected the Nez Perce with Chief Joseph and the other Nez Perce headmen to enter the park, but they’d already proven that they would take a different route than expected. As the main party moved slowly along the river, Yellow Wolf and fellow scouts took several tourists—George and Emma Cowan and her sister and brother, Frank and Ida Carpenter—as captives. Yellow Wolf instructed the tourists to turn east, travel along a stream later called Nez Perce Creek, and follow a barely discernable trail through a pine forest to Mary Lake.

Lean Elk, still responsible for the Nez Perce march, kept an eye on the captives and restrained younger warriors who still sought revenge for the attack on their families at the Big Hole. On the way up the trail toward Mary Lake, Lean Elk told the Cowans they could leave. Men in their party escaped into the woods while Emma and her family backtracked until younger warriors surrounded them, shot George Cowan in the leg and then in the head, and threatened the others. Lean Elk and a Nez Perce named Red Scout had followed the tourists to see to their safety, came upon the attack, and stopped the young warriors from further harming the tourists. With Red Scout’s help, Lean Elk took Emma Cowan and Frank and Ida Carpenter, back into custody, leaving George Cowan, who was presumed dead, beside the trail.

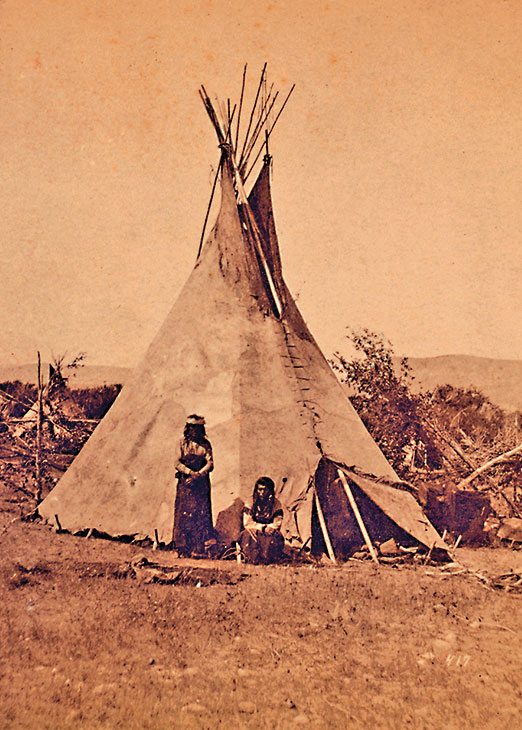

The Indians and the captives continued across Yellowstone Park and into the open meadowland of the Hayden Valley before following the Yellowstone River upstream to Mud Volcano. There, the stench of sulphur mixed with the burping, bubbling sounds of superheated boiling mud stung their noses as they plunged their horses across the river. At Pelican Valley, in the southeastern part of the park, the Indians halted for the day, building fires for each family camp while women fished for supper.

During the evening Nez Perce warriors and headmen joined Chief Joseph and Lean Elk in council near their fire. Emma and her siblings could not understand what was being said, but knew at least a part of the discussion involved their fate, with Joseph arguing on their behalf. The following morning, Lean Elk took the captives, gave them two horses to ride, helped them cross the Yellowstone River, showed them a trail, and told them to “go quick.” They made their way north steadily but cautiously until they met a military scouting party and provided information on the location of the Nez Perce camp, the Indians’ direction of travel and the condition of the people and their animals.

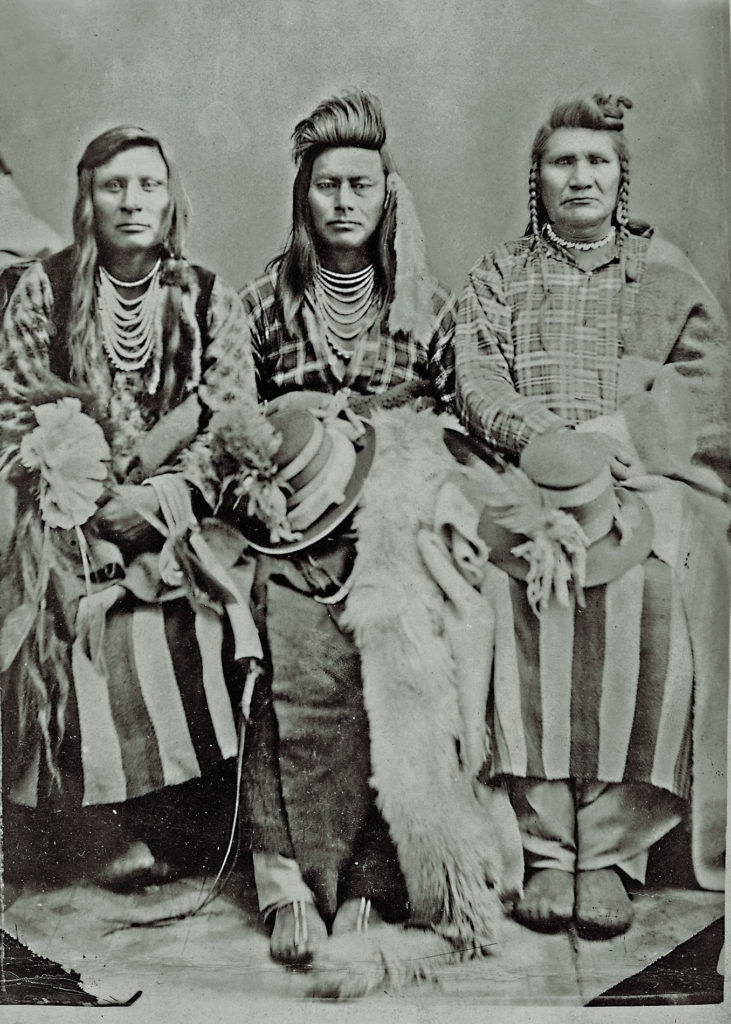

As they had intended from the onset, the Nez Perces and their families now turned toward Crow Indian lands, following Pelican Valley, a broad, 10-mile-long area. While in Yellowstone, the Indians traveled shorter distances each day, resting and recovering from what had already been a grueling trip. They separated into two major groups, one led by Joseph, the other commanded by Looking Glass, as they followed different drainages to Mist Creek Pass and then all descended to the Lamar River on the eastern side of Yellowstone Park. Joseph led his followers north along the Lamar, abandoning dozens of horses and mules that had been cut and injured as they negotiated the rugged terrain. Eventually, they turned east, traveling out of Yellowstone.

General Howard followed the Madison River into Yellowstone Park days after Joseph and the Nez Perces wove their way there and captured the tourists. Howard’s command, with its wagons for support, moved slower than the Nez Perces or the general’s own scouts. Howard’s party found George Cowan, not dead but seriously injured, and placed him in one of the wagons.

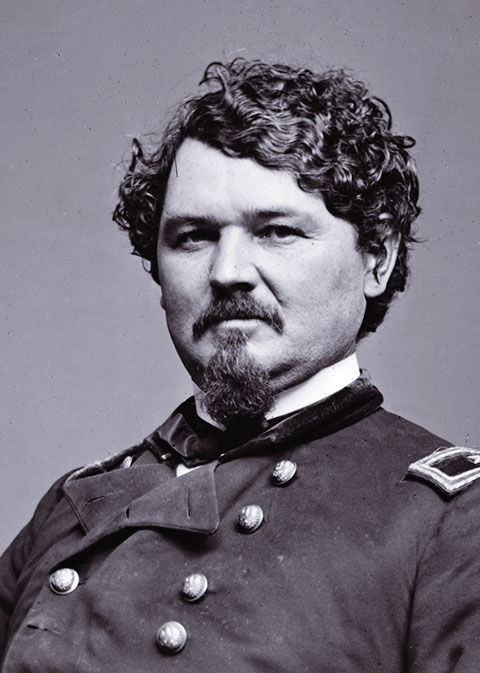

On September 4, Howard’s force reached Mud Volcano and the Yellowstone River ford the Nez Perces had used. He ordered the men to bathe and wash clothing in the hot mineral springs. The wagons had stopped after their difficult descent to the Yellowstone River and the following day Howard discharged the teamsters, telling them to make their way out of the park. The soldiers now used pack mules to carry supplies. Howard himself abandoned the trail of the Nez Perces at the ford near Mud Volcano, following the Yellowstone downstream before riding east, intending to close in on the Indians and corner them. He knew from messages received while he was in Yellowstone that Lt. Col. Samuel D. Sturgis, with 450 mounted men of the 7th Cavalry and several Crow Indian scouts, had moved into the Shoshone River country just east of Yellowstone. This force was poised to encounter the Nez Perces as they left the park but before they could cross onto the open plains of Montana’s buffalo country. Sturgis, a Pennsylvanian, was an experienced Indian fighter, having engaged Jicarilla Apaches in the 1850s and Kiowas and Comanches on the Southern Plains in the 1860s.

Joseph and the other headmen recombined their parties in Sunlight Basin, a big hole ringed by mountains just east of Yellowstone. To move out of it, they could cross over the steep mountains forming part of the Absaroka Range, or they could venture near the narrow defile of the Clark’s Fork River. This canyon was as rugged and seemingly impenetrable as those in the upper reaches of the Snake River near Joseph’s Wallowa homeland. To the dismay of Sturgis and Howard, the headmen chose the river route, and on September 8, again gave the Army the slip.

– Courtesy Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument Digital Archive, NPS.gov. –

The Nez Perces exited Clark’s Fork and headed north, back into Montana, with Lean Elk still in charge of the daily travel. The Crows would not help them and since they could not remain in the buffalo country along the Yellowstone River as intended, they revised their plans. They would travel another three hundred or more miles to Canada and join Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa leader who had escaped there after the June 1876 battle at the Little Bighorn.

The thirteen days the Nez Perces spent crossing through Yellowstone, while giving them a chance to rest and recuperate, allowed the military ample opportunity to get into position. Sturgis, though thwarted in his first effort to stop them as they departed the park, remained in striking distance, and Howard still pushed from behind. There were now hundreds of troops surrounding the Indians, closing in to check their flight.

WE COULD HAVE ESCAPED

What started as an obscure Army-versus-Indian campaign in a remote mountain valley in Idaho became a national drama that summer of 1877. At first, regional newspaper correspondents like Thomas Sutherland of the Portland Daily Standard and writers for the Owyhee Avalanche and Lewiston Teller in Idaho kept the public apprised of the events, but the capture of tourists at Yellowstone brought increased newspaper attention to Joseph and his people. By the time the Nez Perces emerged from the park the story of their hegira was headlined all across America.

The success of the Nez Perces in the engagements in Idaho and western Montana, and the embarrassing fact that a few hundred Indians and their families, with a couple of thousand head of horses, had eluded an ever-growing Army force, began to draw not only attention, but also empathy from people following the story, and in some cases from the very troops who pursued them. “I am actually beginning to admire their bravery and endurance in the face of so many well equipped enemies,” Howard’s field surgeon, Dr. John FitzGerald, said.

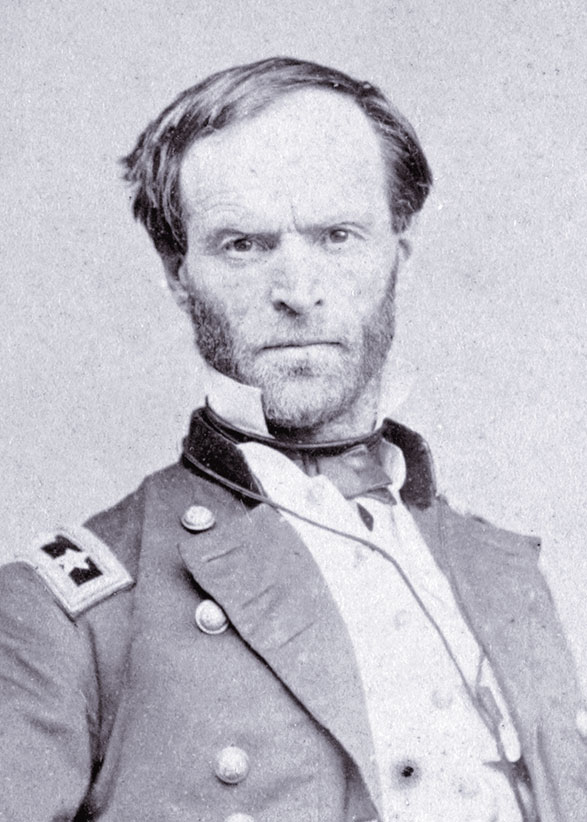

Such was not the view, however, of the Army’s supreme commander, Gen. William T. Sherman, who barely missed running headlong into the Indians during his tour of Yellowstone Park in August. He suggested harsh action: “Their horses, arms and property should be taken away. Many of their leaders [should be] executed,” he said.

Sherman, like other military commanders, believed that most of the tribesmen “will fight hard, skillfully, to the death.”

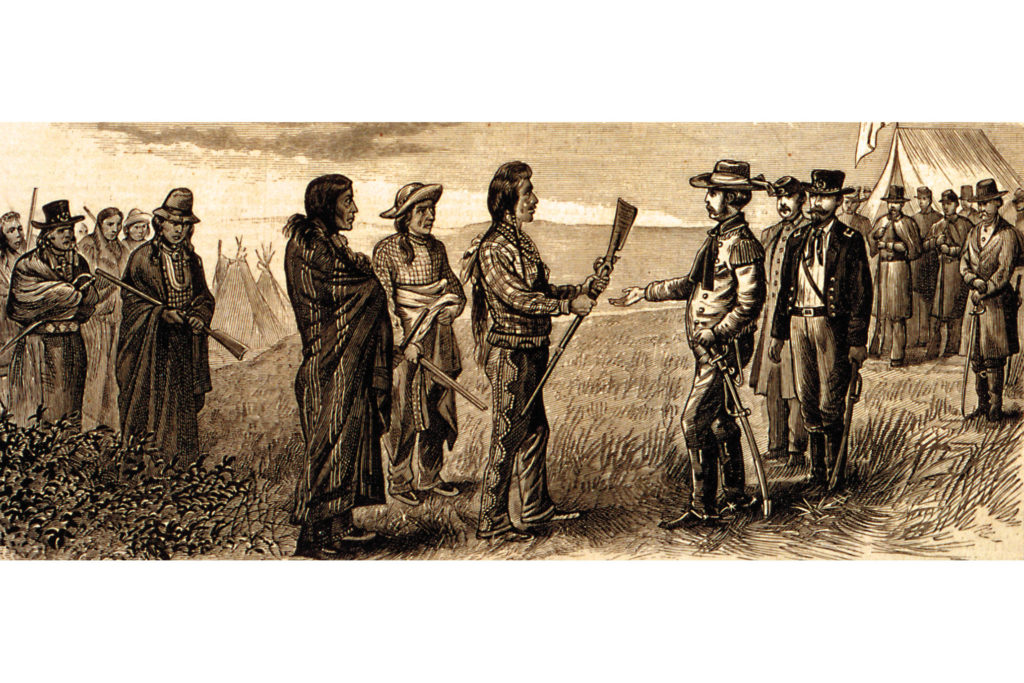

Now out of Yellowstone, the tribal members had a skirmish with troops from the 6th and 7th Cavalry commanded by Sturgis at Canyon Creek, but kept to their trail north toward Canada. There was now another effort to stop them. General Howard, plagued by weary men and horses, and suffering from limited supplies after following the Indians across rough lands impossible for wagons, asked Col. Nelson Miles, commander at the Cantonment on the Tongue River in eastern Montana, to “make every effort in your power to prevent the escape of this hostile band, and at least to hold them in check until I can overtake them.”

A 38-year-old career soldier from Massachusetts, Miles took to the field against the Nez Perces on September 18, just over three months since their flight began. Miles was intimately familiar with the country the Nez Perces were then crossing. During the recent winter campaign, Miles had pursued Sitting Bull into Canada and still monitored the Hunkpapa medicine man’s band.

The Nez Perces were just 80 miles from the Canadian border when Looking Glass again assumed primary leadership for them, replacing Lean Elk. Almost immediately, the travel pace slowed but they traveled another 40 miles. They camped on Snake Creek at the edge of the Bear Paw Mountains* at noon on September 29.

Late that day, General Miles and his 500 troops could see the Bear Paw Mountains when it began raining and then a light snow started. Late that afternoon scouts riding for Miles returned to the main column to report that they had located the Nez Perce trail and knew the camp was nearby.

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

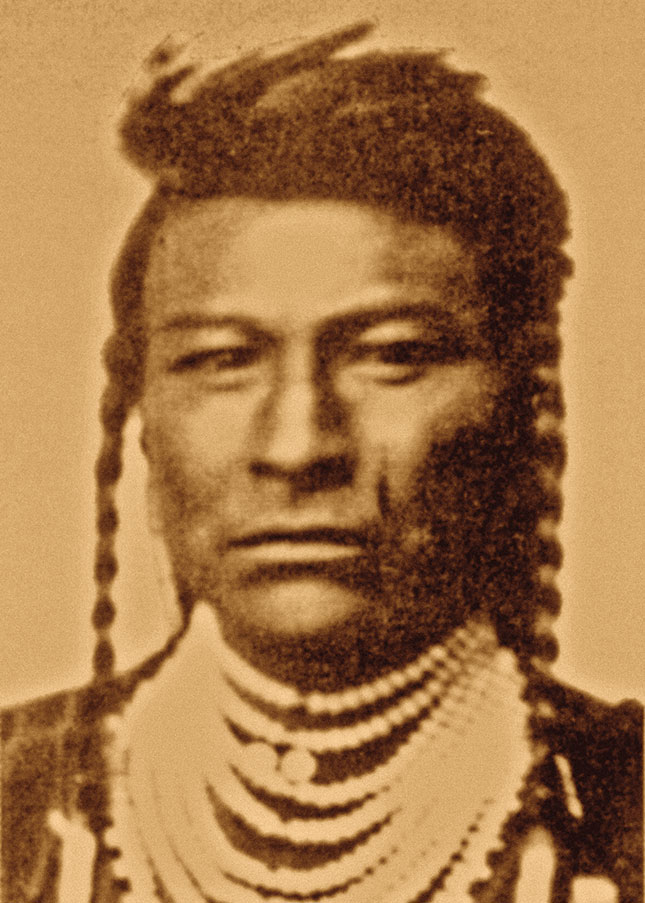

Chief Joseph and his daughter, Sound of Running Water, were at the horse herd early on the morning of September 30, preparing to break camp when they heard the cry “Soldiers, soldiers, soldiers!” as Cheyenne Indian scouts and 7th Cavalry troopers broke over the ridge and swept toward the Nez Perce camp. “We had no knowledge of General Miles’ army until a short time before he charged upon us, cutting our camp in two and capturing nearly all of our horses,” Joseph said.

The cold morning erupted into chaos.

Miles’s troopers attacked with a vengeance. Yellow Wolf watched “hundreds of soldiers charging in two wide, circling wings. They were surrounding our camp.”

– Courtesy NPS.gov. –

– Courtesy NPS.gov. –

“I called my men to drive them back. We fought at close range, not more than 20 steps apart,” Joseph said. Some soldiers fell in the Indian camp and the Nez Percces took their guns and ammunition as they repulsed three separate onslaughts by the troopers.

The day ended in misery for both sides. Dozens of Miles’ troops had been killed or wounded. Several of the Nez Perce leaders also had been killed, including leaders Ollokot, Lean Elk and Toolhoolhoolzote. Indian families were divided as some members fled toward Canada, while others were surrounded by troops and under attack. In their camp, the Nez Perces faced tough decisions. “We could have escaped from Bear Paw Mountain if we had left our wounded, old women and children behind,” Joseph said. “We were unwilling to do this.”

The Battle of Bear Paw became a siege. Over the next four days Joseph met directly with Miles. He was held in the soldier camp against his will, but at the same time soldiers were captured by the Indians. After tense negotiations Joseph was allowed to return to his camp, and the soldiers were released as well. Back in the Indian camp, Joseph met with White Bird and Looking Glass. Before any final decision was made, a military sharpshooter killed Looking Glass. This left White Bird and Chief Joseph to lead the Nez Perces. In the end they agreed to follow their own paths.

Chief Joseph said, “I could not bear to see my wounded men and women suffer any longer; we had lost enough already. My people needed rest. We wanted peace.” He continued, “The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

Joseph’s surrender speech became the defining statement of his life and of his people.

According to Joseph, Miles had “promised that we might return to our country with what stock we had left. I thought we could start again. I believed [him], or I never would have surrendered.”

The night of Joseph’s surrender, White Bird and tribal members who followed him escaped and fled to Canada. Of the 700 souls who had camped along Snake Creek near the Bear Paw Mountains at noon on September 29, 1877, Miles eventually held 448 as prisoners of war. Twenty-five had died on the battlefield and the remainder reached Canada.

This article is an excerpt from Chief Joseph: Guardian of the People, the Spur Award-winning biography by Candy Moulton. See more of Candy’s story about Chief Joseph in this exclusive video:

*The National Park Service uses Bear Paw in the singular for the name of the battle, battlefield and mountains, while the USGS’s official name is Bears Paw Mountains. The NPS spelling has been adopted for consistency in this article.