– Courtesy True West Archives –

October 26, 1881, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, 2:48 p.m. The unforgettable smell of death and gunpowder hung in the air like eternity. The wails of the wounded and dying, the screams and shouts of the witnesses ricocheted down the dusty streets and alleyways of Tombstone into history with the echoes of the earsplitting sounds of Doc Holliday’s shotgun blasts and Colt .45s.

Cowboys Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury lay in the dirt behind the O.K. Corral off Fremont Street, their bodies broken with lead, gunshot wounds bled out, forming patches of mud mixed with manure and urine. Wyatt Earp survived without a scratch, while his brothers Virgil and Morgan were both wounded, and Doc Holliday, just slightly grazed by Frank McLaury’s last shot.

– Carleton Watkins, Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

Time stood still that October in Tombstone, and for the Earps, Clantons, McLaurys and Doc Holliday, Death’s fateful clock had been set for each of them. And while the gambling Georgia gunfighter’s last gasps in Glenwood Springs would be heard by few before his eternal rest, the daring deeds of Doc Holliday continue to be exhumed, honored and celebrated in popular culture, especially in his last healthy refuge, Tombstone, Arizona.

Tombstone’s past is its present. Today, nearly 126 years after John Henry “Doc” Holliday shot his way into history behind the O.K. Corral, his life and legacy can be seen throughout the historic town in Cochise County. His name and visage, like those of his legendary compadres and rivals, welcome visitors to Tombstone every day of the year. Tourists come to walk where the legends walked and fully immerse themselves in the Old West experience of “the town too tough to die.”

Many historic figures were in Tombstone from 1880 to 1882, but Doc and Wyatt’s lives are the most publicized. But how much do we know about Doc’s life in Arizona, his permanent home prior to his last five and a half years of life in Colorado? The best way to follow Doc’s route across Arizona and attend one of Tombstone’s major re-enactment festivals in February, May, September or October is to arrive a week ahead of the event and trace the enigmatic gambler’s 1879-’82 zigzag trail from Prescott to Tucson, and then to Tombstone and Cochise County.

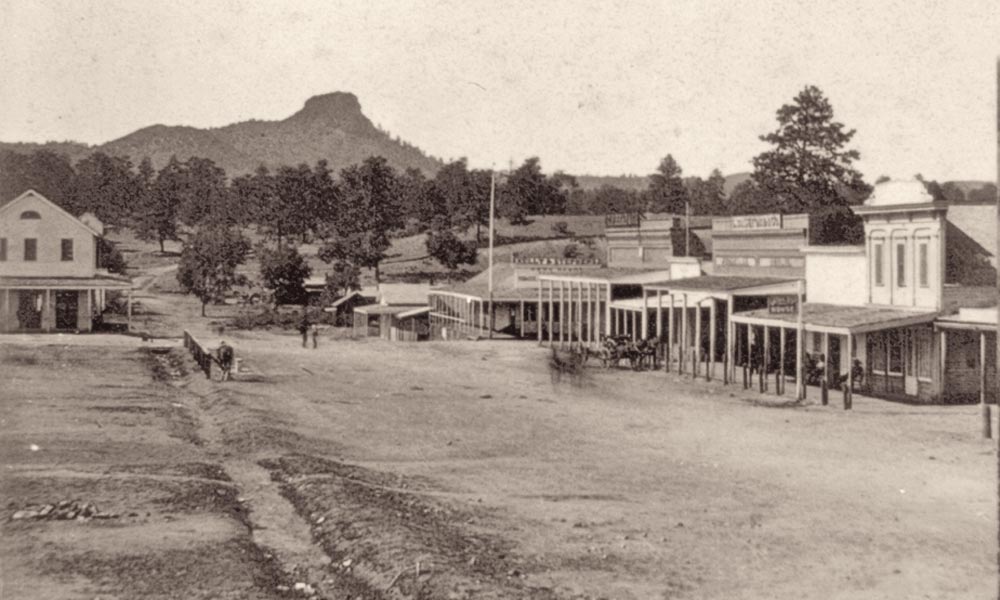

On November 1, 1879, when Doc Holliday and Kate Elder arrived in the Arizona territorial capital of Prescott as passengers in Wyatt and Mattie Earp’s wagon train—which also included Jim and Bessie Earp and Bessie’s two children—the mile-high mining camp was thriving with nearly 2,000 settlers. The Earp-Holliday wagon train would have arrived on the Crook Trail from Camp Verde and driven through Fort Whipple before coming down Gurley Street into the commercial district of Prescott around the Courthouse Square. The Earps would have sought out Virgil and Allie, while Doc and Kate would have sought out a boarding room in the heart of the gambling district on Whiskey Row.

Today, the drive into Prescott on Gurley Street passes the historic Hassayampa Hotel and restored Elks Theater before arriving at the city’s historic Courthouse Square. Parking is plentiful all around the square, which nearly every weekend hosts a festival, concert or event. The actual footsteps of Doc Holliday are not always easy to identify—but, guaranteed, when you walk across the Square, down Montezuma and through the swinging doors of the Palace Restaurant and Saloon, you are striding in the boot steps of the famous Georgia gambler and his notoriously famous compatriots.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

After touring the Square, walk west a short distance to the Sharlot Hall Museum. The centerpiece of the museum complex, a living history center, is the original log-cabin territorial governor’s mansion. Enjoy strolling through the historic grounds, and visiting the indoor exhibits, remembering that when Doc returned to Prescott in May of 1880—after a short gambling respite to pay some debts in Las Vegas, New Mexico—he roomed on Montezuma Street with John J. Gosper, the territorial secretary, and a temperate miner named Richard E. Elliot. While in Prescott, stay at one of the historic downtown hotels, and also plan a tour of the Fort Whipple Museum, housed in a former officers’ quarters at the V.A. Center, just east of downtown.

– Stuart Rosebrook –

To follow Doc’s trail out of Prescott, head south to Phoenix on Interstate 17, also known as the Black Canyon Highway, approximately parallel to the old Southern Pacific Stage road that connected Prescott and the numerous mining camps in between with Phoenix in 1879-’80. While the ghost town of Gillette, where Kate and Doc bid adieu for, respectively, Globe, Arizona, and Las Vegas, New Mexico, in early 1880 (possibly after a final night together at Mrs. H.F. Hart’s Tip-Top Hotel), is way off the highway and only accessible by a four-wheel-drive vehicle, travelers on Doc’s trail should exit at Black Canyon City, and enjoy a meal at Rock Springs Café.

A day spent in downtown Phoenix tracking Doc’s stage layovers would include a walking tour of downtown at Central Avenue and Washington Street, where the stagecoach from Prescott terminated in 1880, and side trips to the State Capitol Museum and to the world-renowned Heard Museum.

– True West Archives –

Doc pulled up stakes from Prescott for the second time in August 1880, but he didn’t go straight to Tombstone. He most likely took the stage back through Phoenix to Maricopa to Tucson.

Today, a drive south through Phoenix on I-17 to Tucson, all the way to Benson and the road south to Tombstone mostly parallels Doc’s stage route and the Earp wagon train’s route.

In Tucson, according to historian Gary Roberts in his biography Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, Holliday stopped at “the St. Augustin Festival, that ran from August 27 to September 16,” and attracted “gamblers from all over the region.” Tucson was the largest city in the Arizona Territory during Doc’s two-year tenure, rivaled only by Tombstone, and in just over six months it would be a major stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad, with a station in Benson as well. Although it is rumored that Doc took a couple of breaks from the tables in Tombstone to play his hand back in

Tucson, we know that the last recorded time he visited the Old Pueblo was with Wyatt, Virgil and Allie Earp, Creek Johnson and Sherman McMaster via the Southern Pacific passenger train from Benson on March 20, 1882. That evening, as the train pulled out of the station, Wyatt avenged his younger brother Morgan’s murder, leaving the bloody, shot- gunned corpse of his accused murderer, cowboy Frank Stilwell, on the tracks.

– Courtesy New York Public Library –

Visitors tracing Doc’s steps in Tucson should start at the Arizona Historical Society Museum, the flagship of the society’s history centers. Afterwards, take a tour of Southern Arizona Transportation Museum adjacent to Amtrak’s historic Southern Pacific Depot, where bronze likenesses of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday stand ever-vigilant near the spot where Frank Stilwell died. Nearby are the historic Hotel Congress, St. Augustine Cathedral and several good restaurants, including El Charro Café, billed as “the oldest continuously family-owned Mexican restaurant in the USA.”

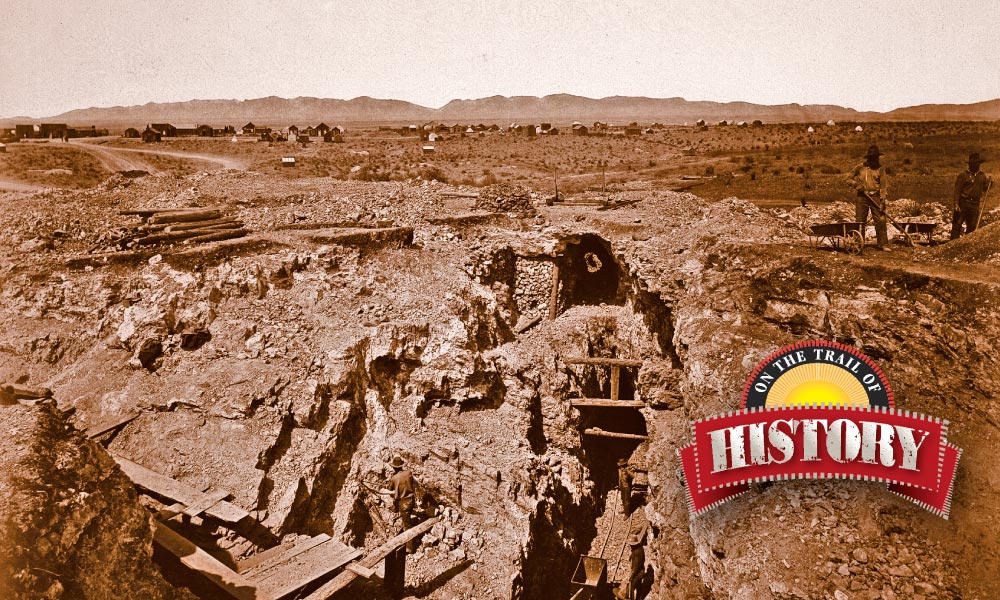

When Doc finally reached Tombstone by stagecoach around September 14, 1880, he took a room at one of the silver camp’s hotels, possibly the Cosmopolitan. Wyatt Earp had been deputy sheriff since July; Virgil had acquired his appointment

as Deputy U.S. Marshall before he left Prescott; Morgan was a Wells Fargo shotgun guard; and oldest brother, James, was employed at Vogan & Flynn’s Saloon. For the next 18 months, Holliday would find himself hard in the mix of competing political and gambling factions, all vying for control of the silver town’s booming enterprises of vice. Doc’s friendship with Wyatt would strengthen while the gambler tried to keep a low profile—difficult at best. He invested in mining and water claims, held a faro bank at the Alhambra Saloon and tried to rectify his on again-off again relationship with Kate Elder.

– True West Archives –

Most visitors to Tombstone today will arrive on State Route 80, which becomes Fremont Street inside the city limits. The historic district, now closed to vehicular traffic, is easily accessible from convenient public parking. Plan on enjoying many of the most famous sites in the pedestrian-only areas of Fremont, Allen and Toughnut between Third and Sixth. Like Prescott, fire ravaged Tombstone, the worst occurring May 25, 1882, destroying many of the original locations that defined Doc’s life there. Nonetheless, visitors to Tombstone in 2017 should not miss tours of the historic Birdcage Saloon, Crystal Palace Saloon, Oriental Saloon Building, O.K. Corral and Historama, the Tombstone 1878 Underground Tour, Boothill Graveyard, Old Tombstone Courthouse State Historical Park and Tombstone Epitaph Museum. Buy a ticket and ride on the Old Tombstone Historical Tour stagecoach and, after the sun goes down, take the Gunfighter and Ghost Tours that start at Big Nose Kate’s Saloon.

Tracking Doc in and around is not as easy as walking the streets of Tombstone. He did go to Charleston and Contention City, both ghost towns abandoned long ago, and what foundations are left of the towns are protected within the San Pedro National Riparian Conservation Area. His Vendetta Ride with Wyatt’s posse after March 18, 1882, went all over the back- country of the Whetstone and Dragoon mountains, before they rode north through Dragoon (known then as Summit Station) to Henry Hooker’s Sierra Bonita Ranch in Graham County, which is still privately held by his descendants. Doc’s last weeks in Arizona in late March and early April 1882 were spent in the saddle, with Wyatt’s posse riding to and from Hooker’s Ranch to Tombstone, north to Fort Grant and then east to Silver City, New Mexico, where they sold their horses for stage fare to Deming, and the northbound train to Albuquerque and eventual exile in Colorado.

– Courtesy Cochise County Tourism –

Doc never returned. His dream of striking it big in Arizona Territory was left in the mud and the blood of Tombstone’s Fremont Street. But his spirit and legend live on all across the Grand Canyon State—and that is a dream he could never have imagined.

Stuart Rosebrook is the senior editor of True West magazine. He is greatly indebted to the research of Gary Roberts in his biography Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend and Casey Tefertiller in his biography Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend.