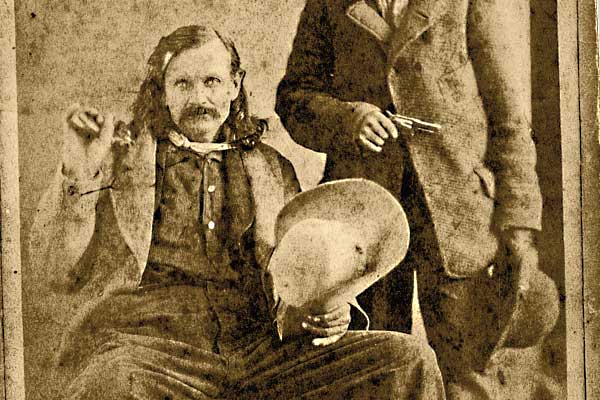

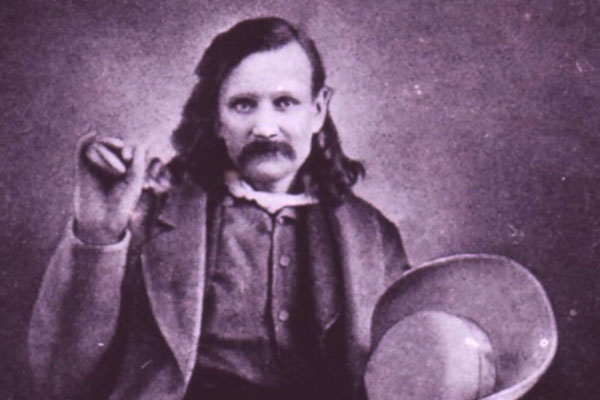

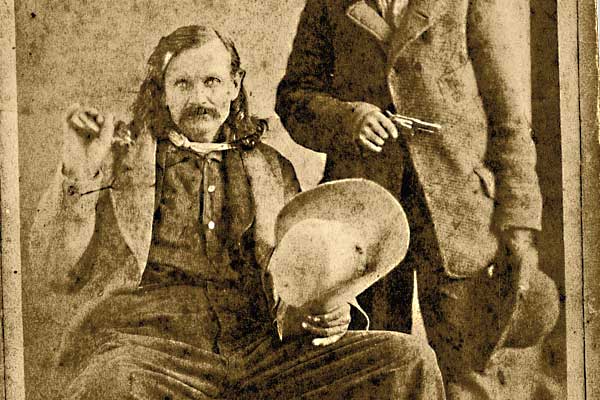

Pioneer Jack Swilling should be remembered for his many contributions to Arizona—but his legacy is clouded by a robbery charge.Born John W. Swilling on April Fool’s Day, 1830, in South Carolina, he spent his first quarter-century in the South.

Pioneer Jack Swilling should be remembered for his many contributions to Arizona—but his legacy is clouded by a robbery charge.Born John W. Swilling on April Fool’s Day, 1830, in South Carolina, he spent his first quarter-century in the South.

Details about his early life are cloudy. He suffered a broken skull and a gunshot to the back in 1854, but he did not reveal how he got the injuries. Those physical problems, though, led to a lifetime addiction to alcohol and opiates, which probably encouraged him to spin yarns. On his 26th birthday, Swilling moved west.

Over the next several years, he worked as a teamster, miner, bartender and saloon owner, U.S. Army scout, Indian fighter, farmer and businessman. He served during the Civil War—on both sides. During and after that tumultuous period, Swilling helped create two of Arizona’s most important cities.

In 1863, three years after Swilling had first explored the Bradshaw Mountains, he guided Joseph R. Walker’s expedition that resulted in a gold rush in the area—and the settlement of the town of Prescott. Swilling made a small fortune.

By 1867, he and his family were living in the Salt River Valley. He convinced associates to utilize ancient canals to bring water to the valley, and farmers flocked to the area. It was called Phoenix.

In 1878, despite his failing health, the adventurer headed to the Wickenburg Mountains with two pals, looking for the remains of Col. Jacob Snively, a friend and fellow prospector who had been killed by Apaches seven years before.

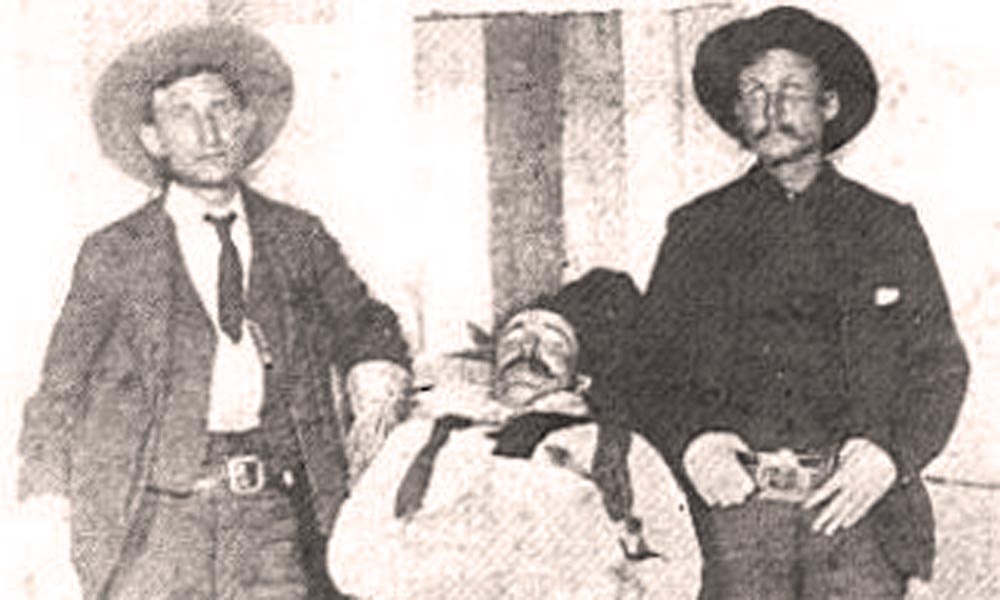

During the time of their journey, on April 19, three men robbed a stage near Wickenburg—and the description of the suspects matched Swilling and company. Word got around that Swilling had told drinking buddies how robbing the stage would be easy and lucrative. He and his friends were arrested.

The sickly Swilling had to be carried to the stagecoach that took him to the hot, dirty and unhealthy jail in Yuma. He wrote a letter to the public, sharing his background and defending himself against the robbery charges.

His plea for help did no good. Swilling died in his cell on August 12.

Over the next few weeks, authorities identified the real stage robbers. Swilling and his friends were cleared of the crime.

Swilling’s final resting place is another cloudy chapter in his life. His grave was among the many lost 25 years later, when a railroad yard was built over Yuma’s pioneer cemetery. Local lore states that Swilling’s body may have been moved to the new Yuma cemetery.

No matter where his bones may rest, let’s remember Swilling as a vital Arizona pioneer—and downplay the sad ending to his tale.