April 30, 1884

April 30, 1884

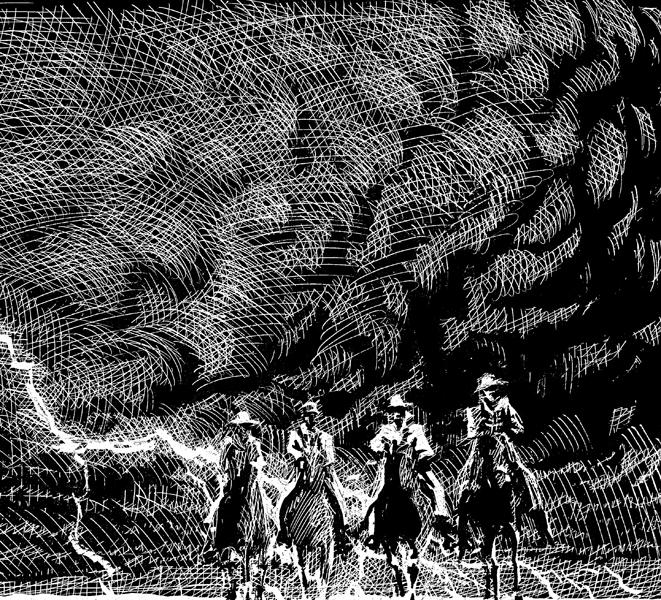

A heavy spring thunder-shower sweeps across Main Street in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, as four riders splash up Kansas Avenue from the west.

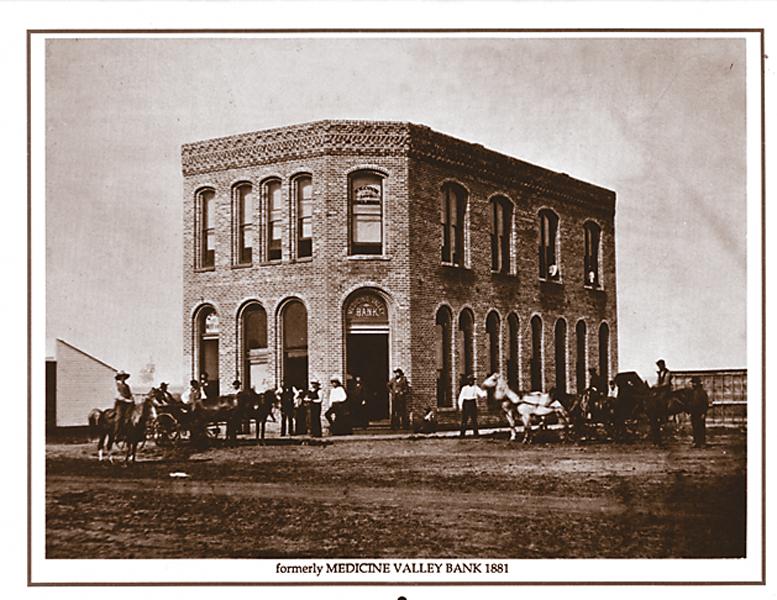

They rein up to a coal shed behind the Medicine Valley Bank. While one man stays with the horses, three others walk briskly along the sidewalk. Two men enter the side door of the bank, while the third heads to the front door. The robber at the front door brandishes his Winchester and tells the two bankers to throw up their hands (perhaps because of the heavy rain, there are no customers in the bank). Cashier George Geppert complies, but bank President E.W. Payne, seated at his desk, reaches for a pistol.

Across the street from the bank, Reverend George Friedley hears gunshots and alerts Marshal Sam Denn, who is standing in front of Herrington & Smith’s grocery store. Denn steps onto the muddy street and, spying the outlaw holding the horses, opens fire on him.

The fight is on as a robber armed with a Winchester steps outside the bank and fires at the approaching townspeople, several of whom have armed themselves.

Leaving behind a sack and a pistol, the bank robbers break for their horses, but frantically fumble with the stiff, wet reins, which won’t untie easily. Finally mounting up, the outlaws gallop south out of town.

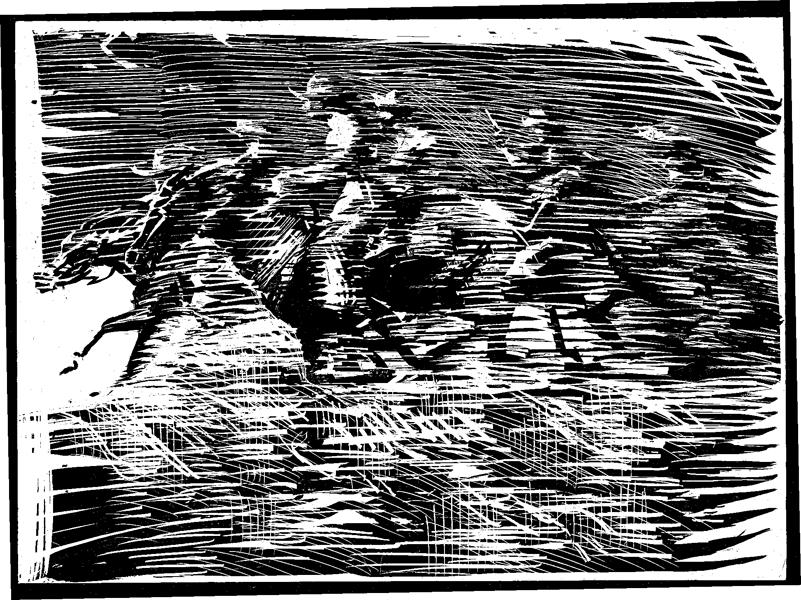

Directly across Kansas Avenue from the bank, the livery stable doors burst open and 10 cowboys explode out onto the muddy street and give chase. (The cowboys were waiting out the storm in the stable before heading to a local roundup.) The instant posse overtakes the startled robbers before they even make it out of town. More shots are fired by the robbers, but the locals, led by Barney O’Connor, Vernon Lytle and Wayne McKinney, return fire and stay on the heels of

the brigands.

Two and a half miles south of town, an outlaw’s horse gives out. Another robber picks him up, and the outlaws ride up into a box canyon to make a stand. Quickly surrounded by the impromptu posse, the robbers hold out for several hours but give up before more reinforcements from town arrive. As the outlaws are brought back to town, the citizens are shocked to discover that all the robbers are well known in Medicine Lodge. Incredibly, two of the outlaws are lawmen from a nearby county and one of them is the Caldwell city marshal.

At the bank, cashier Geppert is found dead in the vault with two gunshot wounds, while E.W. Payne writhes on the floor from the pain of a pistol ball that entered his back near the right shoulder blade (he lives until Thursday, May 1).

Soaked and humiliated by their relatively easy capture, the outlaws are forced to pose for a photo before being thrown in the wooden jail. They will never pose for a photograph again.

The Chase Down

Cowboy posse explodes out of the livery stable across the street from the bank, surprising the outlaws.

Henry Brown dismounts and fires several shots, trying to dissuade the locals from pursuit.

The robbers cross Medicine Lodge River, where one of them fatally shoots a dog from a nearby camp.

Posseman Barney O’Connor rides a borrowed nag (he was running an errand during the robbery and another posse member took his horse). He tops a rise, guesses the outlaws’ destination and cuts across the open grassland, forcing the robbers into the mouth of a box canyon where they are quickly surrounded.

After a futile gunfight with only slight injuries, Henry Brown yells that he will give up on the condition that he and his fellow robbers will not be mobbed. The posse members agree. Brown climbs up to a ledge (see red circle, above) and surrenders.

As William Smith hands over his weapons, he says to his pards, “Boys, I came into it with you, and I’ll go out and die with you.” Truer words were never spoken.

Impending Doom

After the captors assure the robbers that they will not be mobbed, the outlaws are confronted with cries of “Hang them! Hang them!” as the posse members bring them up Main Street. Incredibly, the posse stops at a cafe to feed the suspects. After eating, the outlaws are secured with one set of leg irons and a pair of handcuffs. Brown and Wesley get the leg iron, plus their hands are tied behind them with rope; Wheeler gets his right wrist cuffed to Smith’s left. The prisoners then walk to the jail, enduring strong abuse from citizens the entire way.

When the rain stops, the prisoners are escorted outside the jail for a picture. The photographer also takes pictures of the bank and the box canyon where the outlaws were captured.

Back in jail, the prisoners are given dry clothing and writing materials. At dusk, Henry Brown writes:

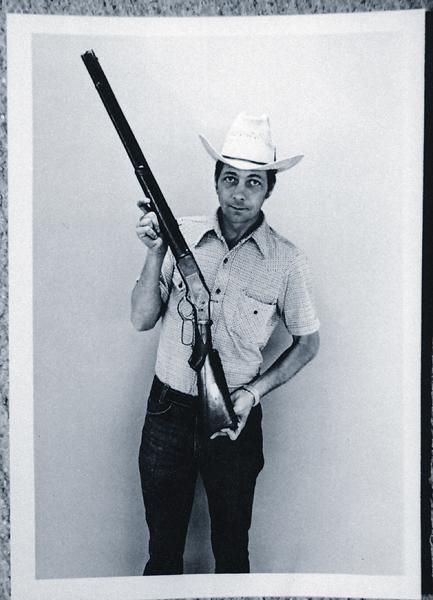

Darling Wife:—I am in jail here. Four of us tried to rob the bank here, and one man shot one of the men in the bank … I will send you all of my things, and you can sell them, but keep the Winchester [although some disagree, this mention implies he used the special presentation Winchester in the holdup] … we would not have been arrested, but one of our horses gave out, and we could not leave him alone … If a mob does not kill us we will come out all right after while.

At about nine that night, three shots are heard, signaling citizens to join a large mob that is converging at the jail.

The Newlyweds

By 1883, Henry Brown had turned his life around. After riding for several years with known outlaws, he came under the wing of a Caldwell, Kansas, family, whose members recommended him to the city as a possible lawman. Rising quickly to the position of marshal, Brown so impressed the people of Caldwell that they presented him with a custom, gold-plated Winchester rifle. In March 1884, the 26 year old married a 22-year-old local girl, Alice Maude Levagood, and bought a house. But old habits die hard. Brown asked the mayor for time off to hunt outlaws in the Oklahoma Territory and left his new bride on Sunday night, April 27. She never saw him again.

Hell to Pay

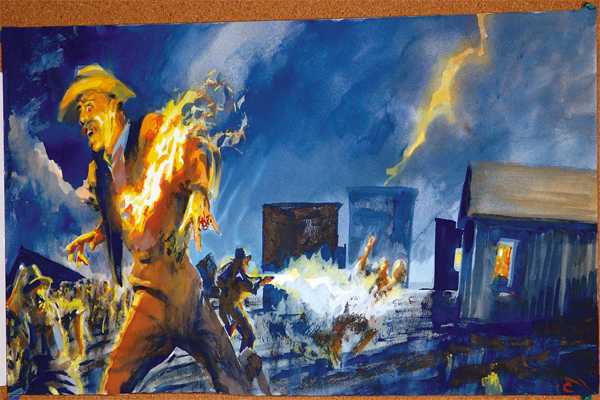

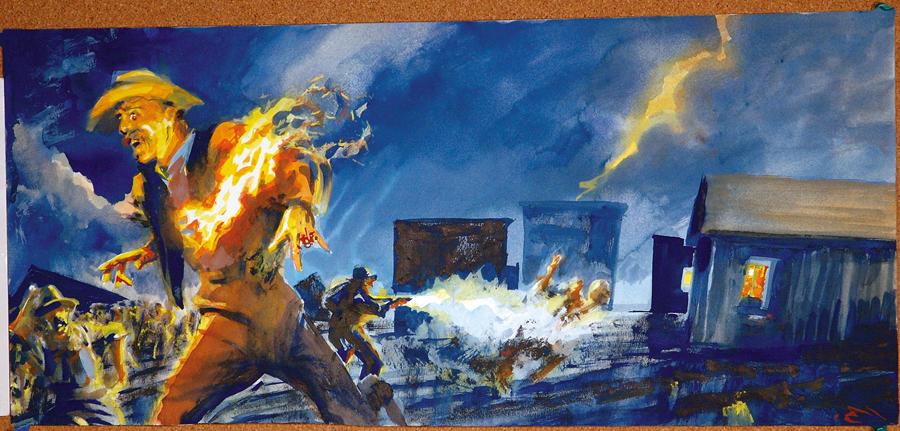

Three shots are heard at about nine p.m. and several hundred men swarm the jail and sweep the guards aside. Having slipped off his boot (and the leg iron with it), Brown crouches by the door. When it swings open, he plunges into the crowd, fighting his way into the open, with Wheeler behind him. Several shots are fired at close range, but Brown, only slightly wounded, clears the crowd and makes for an open alley. A local farmer, Billy Kelley, jerks up a double-barreled shotgun and triggers both barrels, cutting Brown almost in half.

Meanwhile, Wheeler has been shot several times, and he staggers through the crowd with his vest on fire, ignited by the point-blank explosions. A bullet rips off two fingers of his left hand (above), and a Winchester ball shatters his right arm. He still makes it another 100 yards as the mob chases him and pumps bullets into him, until he falls. Incredibly, he’s still alive. The mob jerks him to his feet and, along with Wesley and Smith, the three are taken to the creek bottom. Wheeler whispers a confession, then adds, “Oh, men, spare my life. There’s other fellows mixed up in this, and I will tell you everything if only you will spare my life.”

The outlaws are asked if they have any last words. Wesley says he has a mother in Texas and requests that she not be told of his fate. Smith shows no fear and asks that his saddle be sold and the money sent to his mother, also in Texas. The three men are strung up with two ropes, with two of them (Smith and Wesley) sharing the same rope. Wheeler’s bleating can be heard several blocks away. And then it’s deathly quiet.

Henry Brown Rode with Billy the Kid

Henry Brown rode with the notorious Billy the Kid during the bloody Lincoln County War in New Mexico Territory (1878-1880). Henry (sometimes styled as Hendry) fought in several of the more legendary fights involving Billy the Kid, including the ambush of Sheriff Brady, the fight at Blazer’s Mill and the climactic McSween house fight, known locally as the “Big Killing.” Like the Kid, Brown bravely escaped that death trap. He eventually landed in Tascosa, Texas, where he served briefly as a marshal and constable. But Henry Brown was a notorious hothead, states Bill O’Neal, his biographer, and the sheriff relieved Brown of his marshal duties in Tascosa because Brown “was always wanting to fight and get his mane up.” Brown was also later fired from the LIT ranch “because he was always on the warpath.”

After Tascosa, Brown worked for a brief time at a ranch in Woods County, Oklahoma, where his foreman was Barney O’Connor (the same cowboy who would later help capture Brown in a box canyon after the bank robbery in Medicine Lodge).

Drifting into Kansas, Brown found work as a peace officer in the wild and untamed cowtown of Caldwell, Kansas, where he distinguished him-self as a competent lawman.

As for Brown’s mixed legacy and tragic end, one current Caldwell citizen maintains, “He was a prick when he rode with the Kid and he died a prick.”

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Caldwell residents were horrified by the actions of their marshal and deputy (at first they refused to believe it) but finally sent a formal apology to Medicine Lodge. A public auction was held offering the horses and saddles of the dead outlaws. Smith’s saddle went for $10, the rest brought about $25 each. Wesley’s gray horse got $120 and Smith’s, $123.50.

Widowed a month into her marriage, Alice Maude Levagood graduated from college, moved to Devil’s Lake, North Dakota, and taught school. She also proved out a land patent, sold it to her adoptive brother and then moved to Frankfort, Indiana, where she became a nurse and a superintendent of an asylum. Late in life, she wrote a short story of her life. The only mention of her husband is that she married H.N. Brown in 1883, adding cryptically, “Mr. Brown passed away many years ago.”

Recommended: Henry Brown: The Outlaw-Marshal by Bill O’Neal, published by The Early West; Meandering Medicine Lodge: The 1880’s by Beverly McCollom, self-published and available at the Stockade Museum in Medicine Lodge.