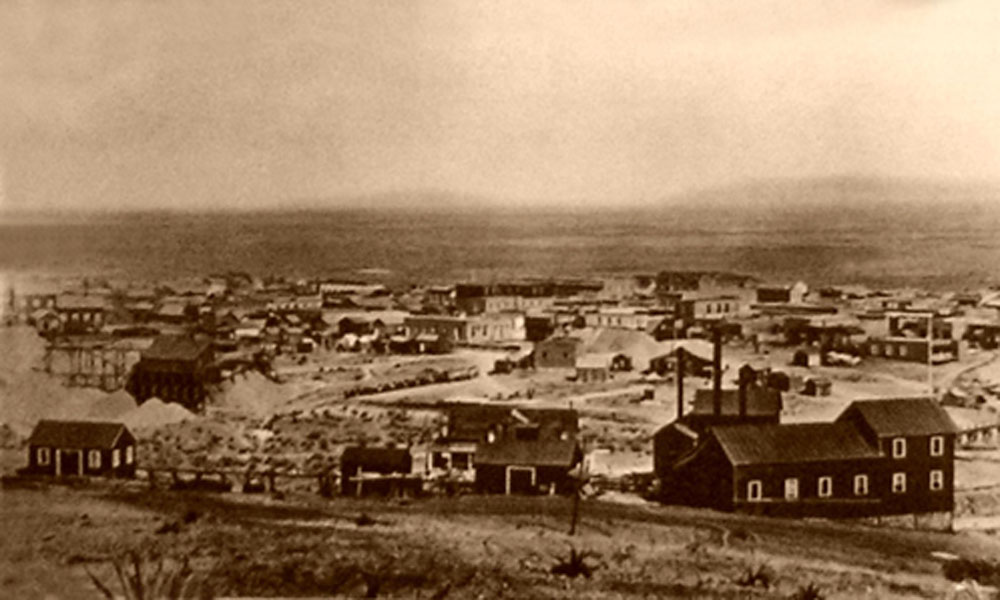

That’s how journalist Clara Spalding Brown first described Tombstone, Arizona Territory, when she arrived in June of 1880 from San Diego with her prospector husband. She wrote honest and unflattering portraits of the town in letters and newspaper columns—17 of them contained in Lynn R. Bailey’s “Tombstone from a Women’s Point of View.”

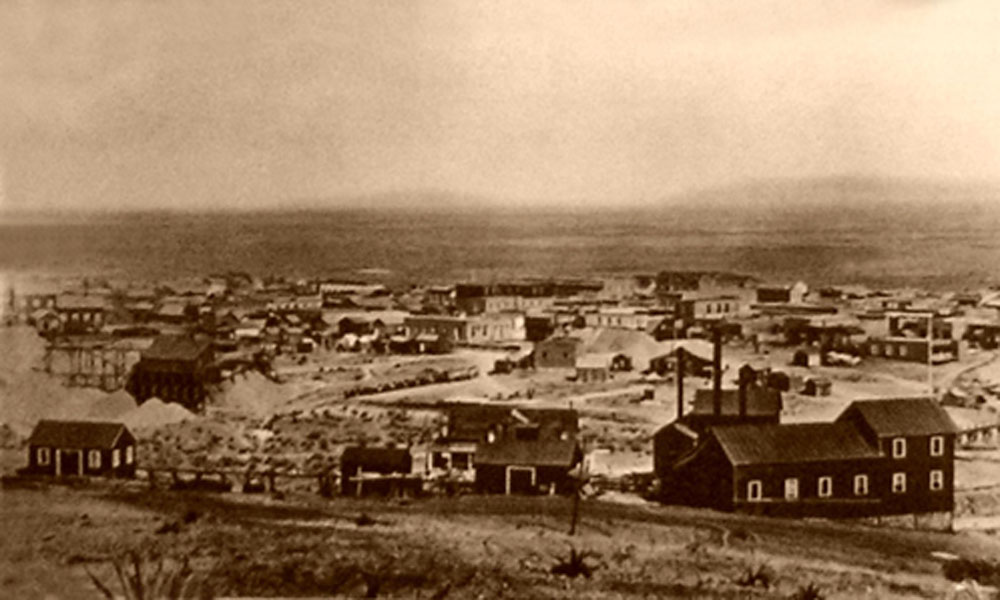

Mrs. Brown found a town of “canvas, frame and adobe” where the only “attractive places” were the liquor and gambling saloons—where she never went—and the only “entertainment” for “honest women” was “a stroll about town after sunset, the only comfortable time of day.” She found church services, teachers and fresh vegetables all skimpy and fresh fruit too expensive. But when she wrote such words in a column for the San Diego Daily Union, she probably got some blowback, since she certainly changed her tone in her next column just two weeks later. But then, the success of the town depended on outside money coming in to mine the hills, so “bad publicity” certainly wouldn’t help—did city officials or businessmen exert pressure on her to “clean up’ her observations? Perhaps. Or maybe she was a woman who could recognize and appreciate real progress.

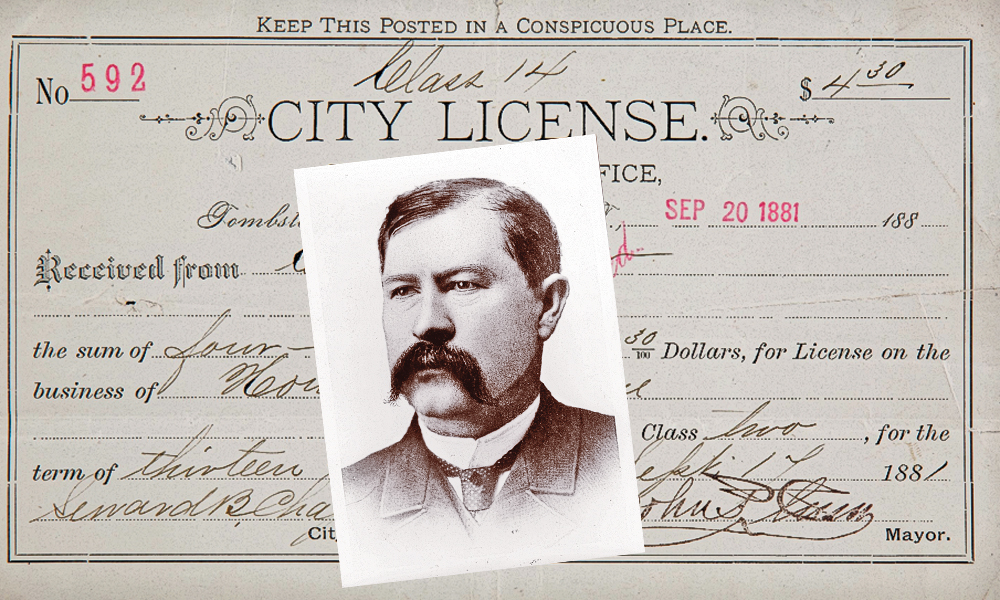

Her second column gushed, “New treasures are daily being unearthed, and there is every reason to believe that Tombstone will not only endure, but greatly increase, for years to come.” She heralded new churches and schools, new saloons and the status of becoming the county seat—along with “the finest adobe structure in Arizona,” the county’s Schieffelin Hall. She happily reported how Tombstone mining stock that had sold a couple years earlier for as little as 12 ½ cents now was worth $80.

And she offered a most interesting tidbit about the aftermath of the Gunfight near the OK Corral: that ten local men guarded the jail to protect the Wyatt Earp gang against further bloodshed. The Browns left Tombstone in 1882, but her columns give an inside and personal look at the “town too tough to die.”