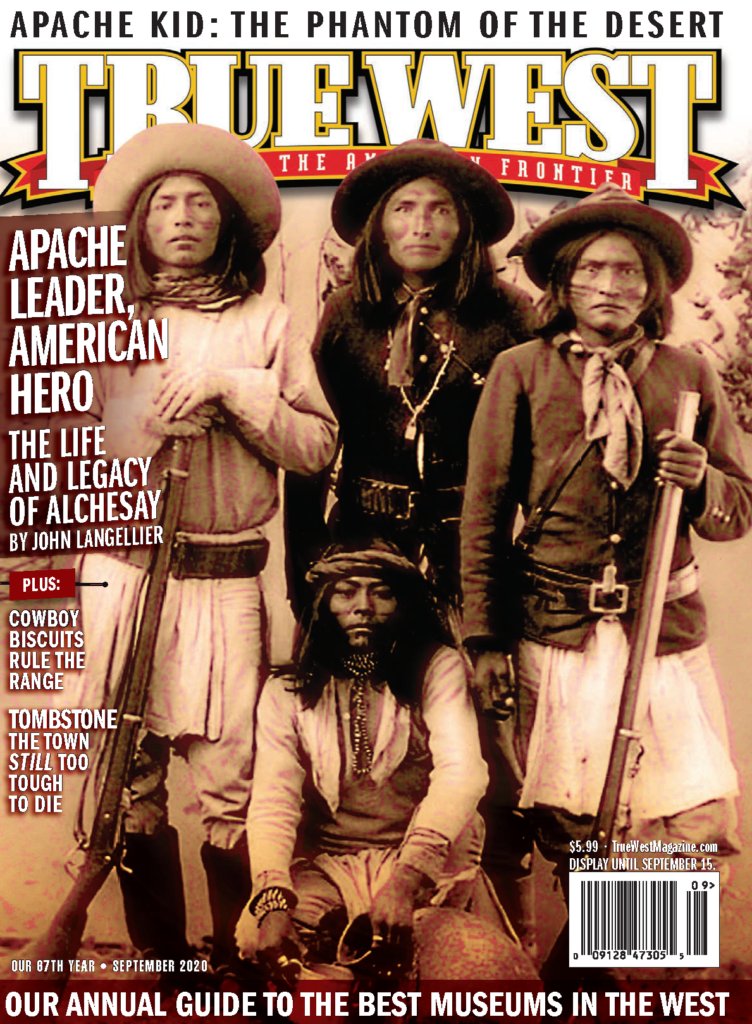

– True West Archives –

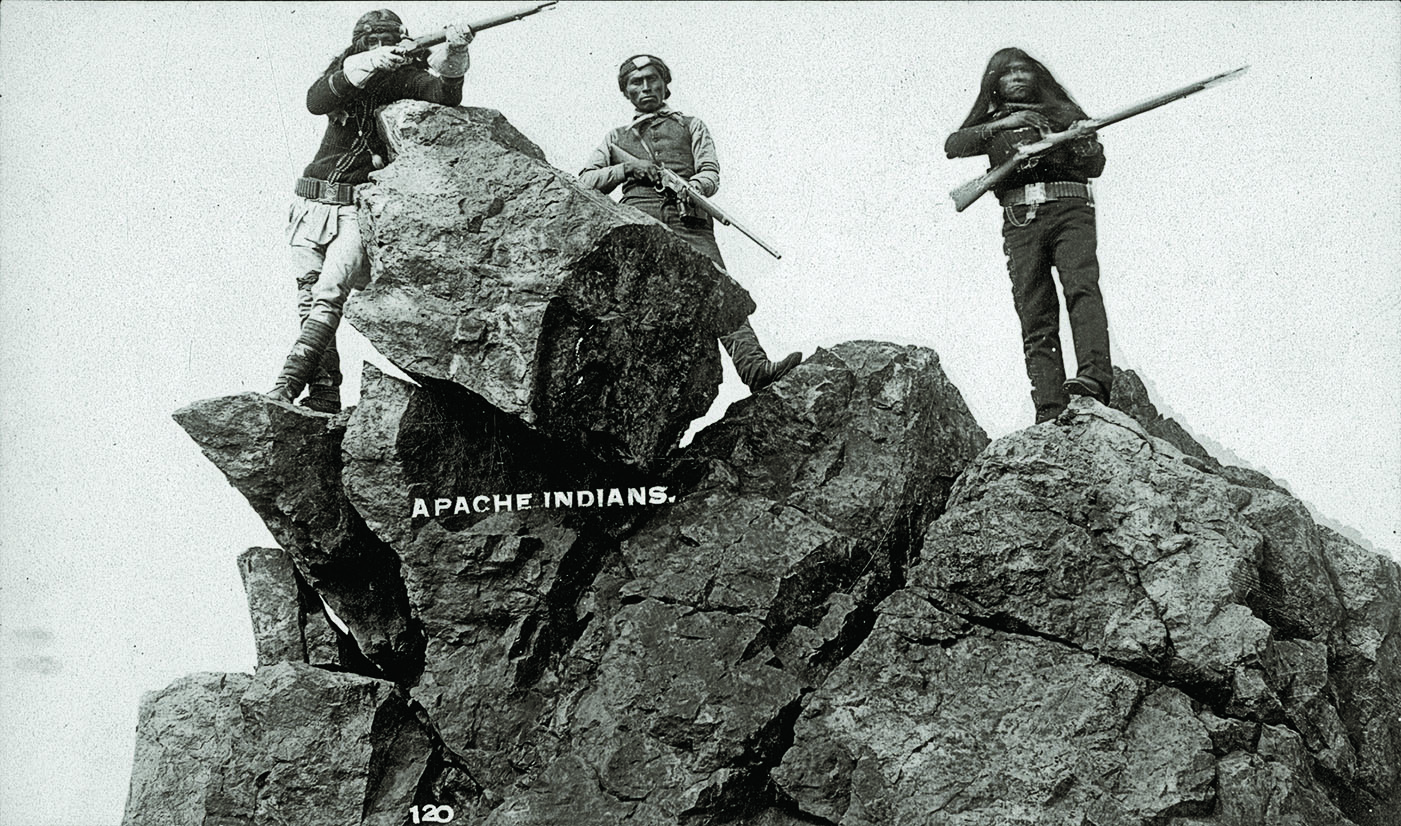

“The Kid was a dark folk hero, a celebrated outlaw. He was at large in Mexico, living off the land, raiding when he felt like it. It was the Old Apache way.”

—Neil Goodwin, as quoted by Paul Andrew Hutton

in The Apache Wars

As lawmen, historians and treasure-hunters have chased the spectral life of the Apache Kid from Mexico’s Sierra Madre to the U.S. National Archives the past 130 years, the elusive outlaw and former Army scout’s life story has grown in reputation and notoriety. Many of the details of his final years living in Mexico and raiding in Arizona remain unknown, although his final days and demise, according to Lynda A. Sánchez in her February 2019 True West article, “The Final Nail in the Apache Kid’s Coffin,” took place in November 1900 in a fight with Mormon settlers in Chihuahua, Mexico.

One of the items that historians have used to possibly identify The Kid was a pair of “French” field glasses, which he famously was known to carry. An Apache scout wearing a set of field glasses was identified as the Apache Kid by C.S. Fly or Mollie Fly on the reverse of a photograph taken in Sonora, Mexico, prior to Geronimo’s surrender in March 1886. As historian Phyllis de la Garza says in her biography The Apache Kid “…at some point in his scouting career Kid began carrying binoculars on a long shoulder strap.”

– True West Archives –

Searching for and correctly identifying images of rarely photographed Old West men and women through closely kept personal possessions can be a key factor in determining provenance for Western historians and photographers. This is also why historians have for decades debated the exact number of existing photos of the Apache Kid and have sought to identify new and confirmed photographs of the elusive outlaw.

So how many actual photos of the Apache Kid exist?

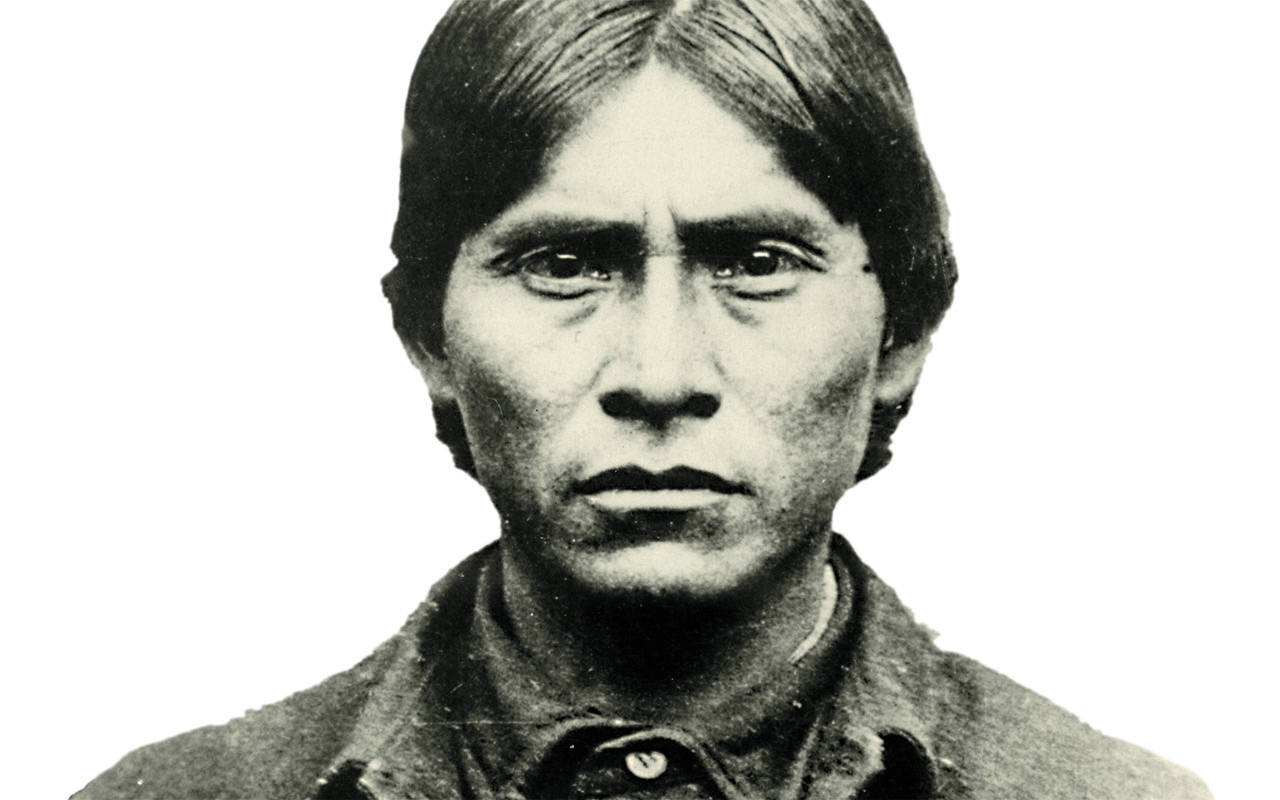

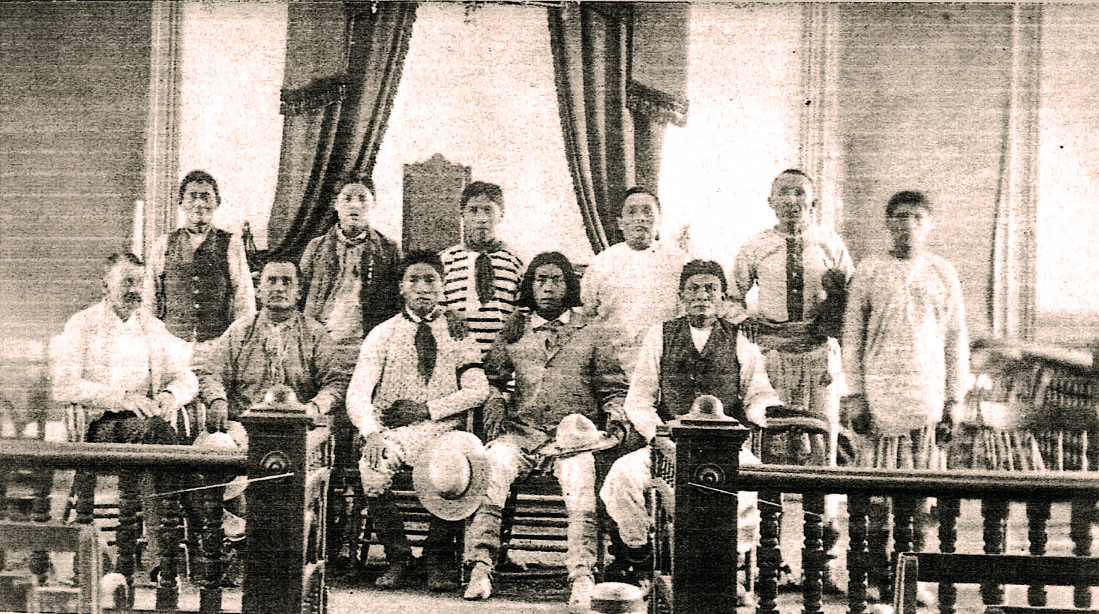

First, historians generally agree that there are at least two known photographs of Kid: a prison mug shot printed on a cabinet card and a group shot of prisoners known famously as “Apache Kid and His Red Devils in 1882 [sic] Kid is 2nd from right standing.”

Second, historians, referencing the verso annotation on the aforementioned C.S. Fly photo of Kid and two other Apache scouts standing amid wickiups in Sonora (Three Shot of Apache Men Near Geronimo’s Camp), have identified one cropped photo—with Kid in the shot—and two other photos of Apache scouts Fly took while accompanying Gen. George Crook in March 1886. An Apache scout with binoculars, the well-known possession of the Apache Kid, is pictured.

The sixth photo in question is a rare October/November 1889 image of five incarcerated prisoners at the Gila County Courthouse in Globe, Arizona Territory. The Apache Wars author Paul Andrew Hutton owns the photograph, which he published in his book, with the confidence that Western historian John Langellier had correctly identified the Apache Kid as one of the five men in the photo.

– Courtesy Abe Hays Collection –

A seventh image, an Arizona courtroom photograph of 11 men, possibly taken during or after Kid’s October-November 1889 trial in Globe, may include the Apache outlaw, according to Kid historian de la Garza. The image, published in Dean Smith’s Arizona Highways Album; The Road to Statehood 1912 (Phoenix, Arizona: Arizona Highways, 1987), is credited to the McLaughlin Collection, the once-famous photo library of Phoenix photographers Herb and Dorothy McLaughlin. I worked with Dorothy when I was a member of the Arizona Highways staff in the 1990s. She and her late-husband had a catalog of 100,000 historical and modern images that is now curated by Arizona State University’s Greater Arizona Archives department.

– True West Archives –

An eighth possible image of Kid, which True West published in July 2019 as an illustration in Frank W. Puncer’s article, “Edgar Rice Burroughs Hunted the Apache Kid,” has been at the center of swirling controversy since its publication.

In our final review before publication, we received an email, supported by three veteran Southwestern historians, that the Kid (on the right end, wearing a campaign hat) was one of the 12 Apache scouts photographed on the parade grounds at an unnamed fort in New Mexico Territory in 1881. Little did we know the reaction the photo would receive from our readers, including biographer Phyllis de la Garza and Western historian and frontier Army uniform and weapon expert, John Langellier.

– True West Archives –

Langellier, who writes True West’s “Collecting the West” column, wrote us and stated emphatically that the photo was “taken sometime after 1885, given that the new five-button blouse and the canvas leggings worn by a few of the scouts were not issued before that time. Also, the figure on the far right appears to be Cut Mouth Mose, and to his right, the Yavapai Medal of Honor recipient, Rowdy.”

– True West Archives –

To Langellier’s response de la Garza answered:

“As for Kid, I am quite positive that is him in the scout lineup. He was 1st sergeant of the scouts and they always stood at the right side in photos. He was tall, and regularly dressed in white man’s garb, etc. Unless he has a definite photo of a scout named Cut Mouth Mose to compare with the Kid’s pictures, I will not believe this is anybody but Kid.”

De la Garza’s answer elicited this detailed response from Dr. Langellier:

“I highly respect Ms. de la Garza, but the photo from NARA has been misidentified as Fort Wingate by many authors, when it is, in fact, Fort Apache. I have included the correct citation from NARA’s Signal Corps collection (Apache FtApache, NARA No. 1892111SC87797) as well as an AHS image of Rowdy seated with his Medal of Honor and Cut Mouth Mose (who variously served as a sergeant and first sergeant during his enlistments) standing to Rowdy’s left. This was after Rowdy had been awarded the Medal of Honor for pursuit of the Apache Kid’s followers under James Watson and Powhatan Clarke of the 10th Cavalry, which, as you know, is the topic of my newest book.

“There is also another issue. The man identified as the Kid wears regulation leggings which were adopted in April 22, 1887, and not procured and available for purchase by soldiers until many months later (no earlier than late June), making it impossible for the Kid to wear these. As Ms. de la Garza knows, the incident that ended the Kid’s days as a scout took place in May of 1887, and by June he was standing court martial. Thus, he could not appear in a photo with other scouts wearing this specific pattern of leggings which I discuss in More Army Blue, based on original U.S. Army quartermaster records.”

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

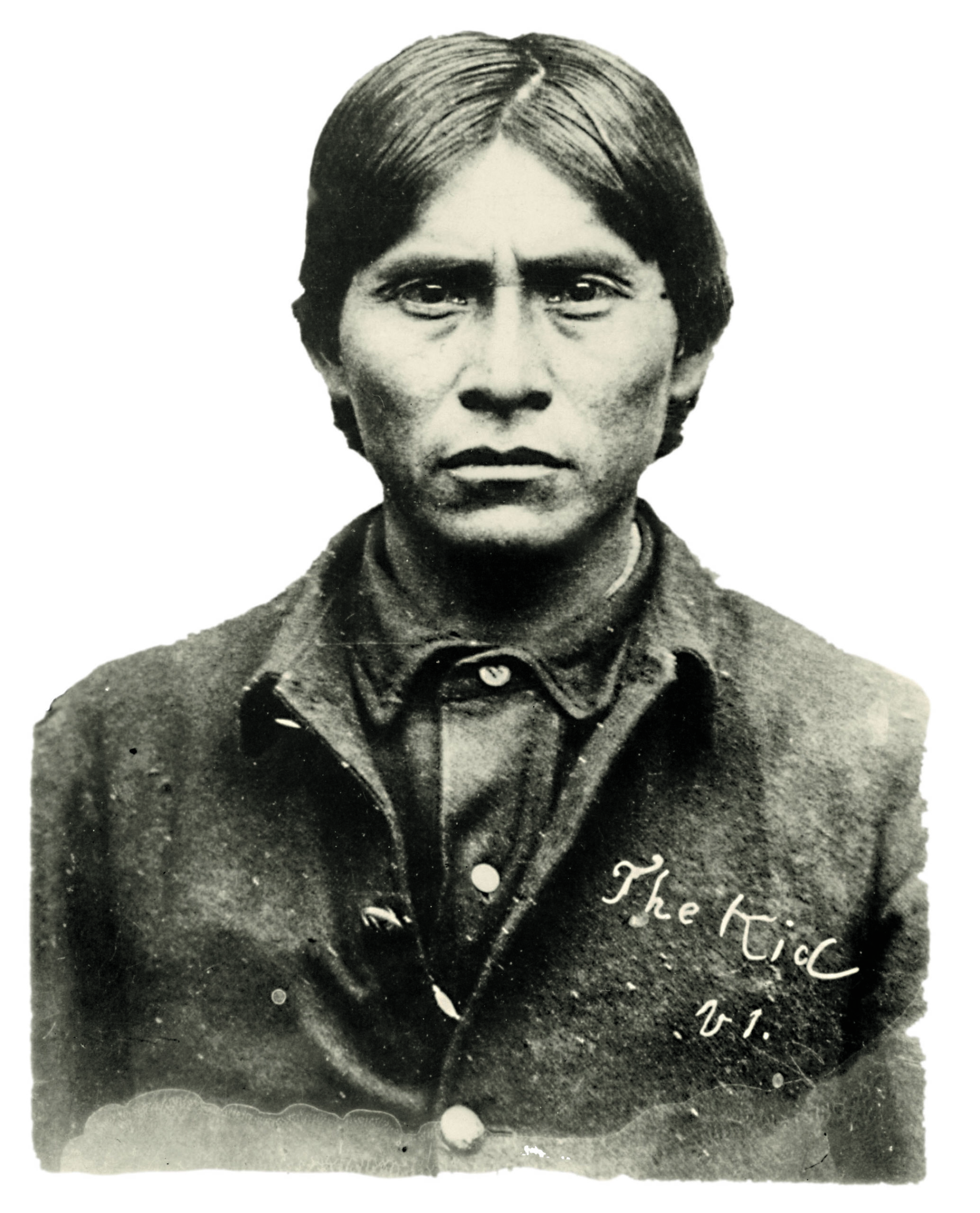

“Apache Kid and His Red Devils”

The prisoners were photographed prior to their bold escape.

After a group of Apache defendants was found guilty in a Gila County district courtroom on October 30, 1889, they were photographed in Globe (above) before they departed by stagecoach for the Yuma Territorial Prison on November 1. Note that the Apache Kid (standing, second from right) is still wearing his brass reservation tag on his left breast pocket, as well as the incorrect date and caption ribbon attached to the photo many years after the fact. When the Apaches got out of the stage near Ripsey Wash, Bach-e-on-al (front row, center, indicted under the name Pash-ten-tah) allegedly slipped free of his handcuffs. He and El-cahn (standing, far left) overpowered Gila County Sheriff Glenn Reynolds as another two Apaches attack hired guard William “Hunkydory” Holmes, who reportedly died of a heart attack before being shot. Hos-cal-te and Sayes (standing, second and third from left) were later recaptured and died in prison. Not shown in the photograph is prisoner Jesus Avott, sentenced to one year in prison for selling a friend’s horse for $50.

– True West Archives –