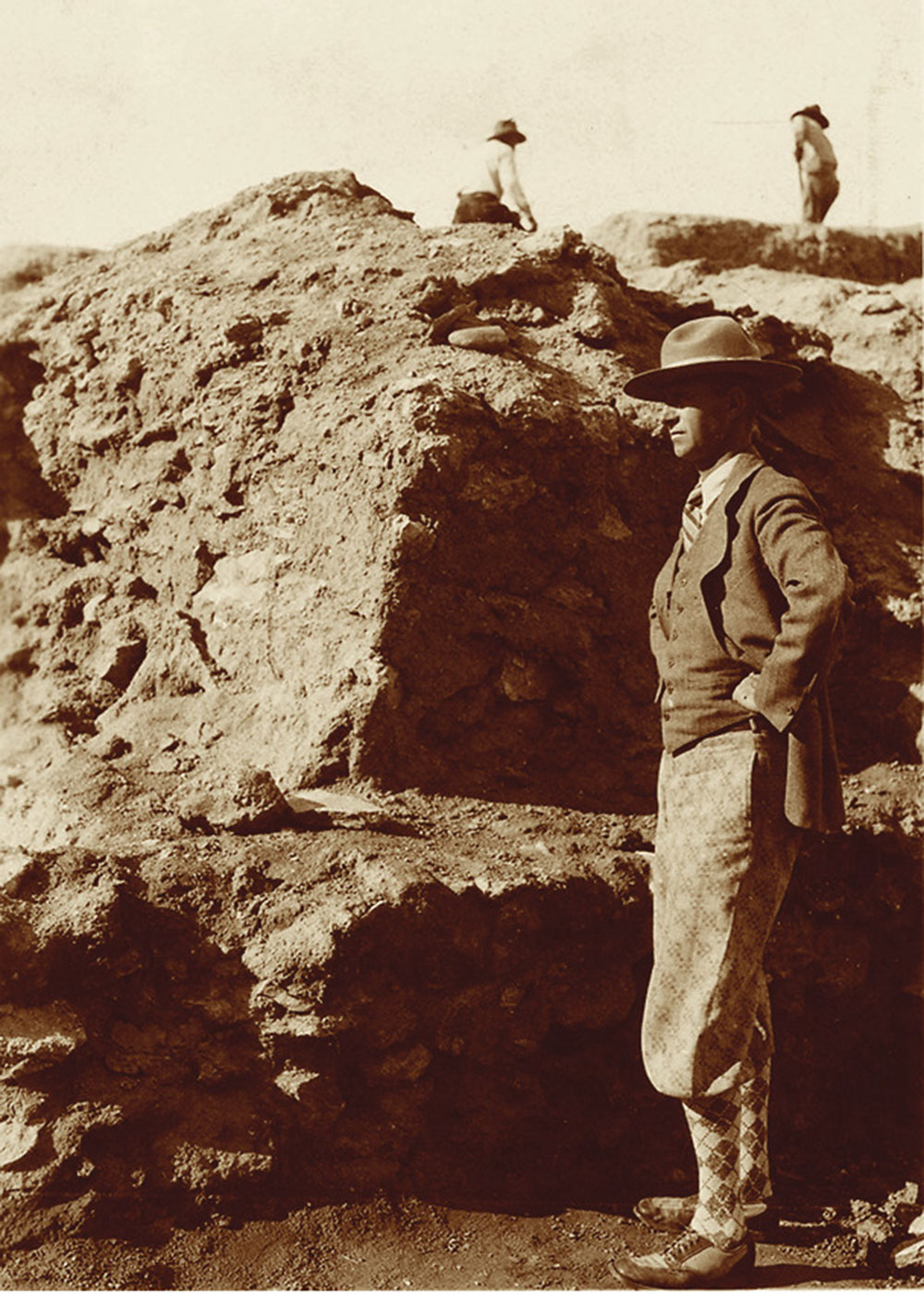

— Courtesy Pueblo Grande Museum and Archeological Park —

The second Phoenix is America’s newest modern city. The first Phoenix was among its oldest—a thriving community 1,000 years before Father Eusebio Kino came to what is now Arizona, centuries before Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

Because of the Pueblo Grande Museum and Archeological Park, we’re still learning about the Hohokam Indians who made the first Phoenix so important—excavations show that by 1350, it had already been one of the largest and most important villages in the area for more than seven centuries.

The Hohokam were gone centuries before any white man arrived—leaving behind a series of irrigation canals that speak to a robust agricultural city, canals directly responsible for the settlement of Phoenix by its founder, Jack Swilling, in the 1860s. Those canal routes are still used to this day to move water throughout this desert city.

— Courtesy Pueblo Grande Museum and Archeological Park —

In October, Pueblo Grande will celebrate its 90th birthday, marking one of Phoenix’s most significant public decisions. It was in 1929—as the country’s economy tanked with the Great Depression—that Phoenix leaders created the nation’s first “city archeologist” to preserve what was becoming obvious: Phoenix was being rebuilt on land that held ancient homes and ceremonial buildings and giant ball courts and 20-foot-high communication mounds.

What they would eventually find is that there are hundreds of prehistoric sites throughout central Phoenix—some are still being uncovered to this day. But Pueblo Grande stands as the one preserved site.

Thousands of visitors every year walk through a piece of the excavated city—a sacred place for Native people—or through the exhibit halls that tell the story of the first people to call this place home. “We’re so close to Sky Harbor Airport that a lot of people with layovers come see the museum,” notes Lorenzo Clark, president of the museum’s auxiliary. “We meet people from all over the world.”

Museum Director Nicole Armstrong-Best said it still amazes her how sophisticated the Pueblo Grande site was in its heyday. She notes that they have preserved just one of the 20-foot-tall platform mounds that were strung along the canals every three miles “so they could signal back and forth to control the flow of water for agriculture.”

She notes the anniversary will include events at the museum, as well as exhibits at Phoenix City Hall, the Airport Museum and Terminal 3 at Sky Harbor Airport, each with “90 objects celebrating 90 years.”

As it turns out, 1929 was a particularly stellar moment for Phoenix to honor its past. That same year, two leading citizens—Dwight B. and Maie Bartlett Heard—turned their home into a private museum to showcase their collection of Native items, including the pieces they found at the La Ciudad Indian Ruin they purchased in 1926 (not far from Pueblo Grande).

They went on to create a museum “dedicated to the advancement of the American Indian.” Today’s Heard Museum, also celebrating its 90th birthday this year, is now internationally recognized.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.