– True West Archives –

If a singular word describes the 1897 Klondike Gold Rush, it is audacious. Everything about this rush for riches was audacious; the people, their lifestyles, the obstacles they overcame, the land from which they tickled wealth.

Prospector Clarence Berry illustrated this lavishness best. Outside his cabin, at the height of the gold rush, he placed a coffee can filled with gold nuggets and a whiskey bottle, with a sign reading, “Help Yourself!” He eventually left the Klondike with $1.5 million (nearly $45 million today).

George Carmack, known as Lying George, sparked the gold rush when he walked into Bill McPhee’s smoke-filled saloon in the settlement of Forty Mile in Canada’s Yukon Territory in August 1896. He ordered a round of drinks for the house, shouting, “There’s been a big strike upriver!”

He, his brother-in-law, “Skookum” Jim Mason, and Jim’s nephew Charlie Mason had just struck gold.

The Men Who Sparked the Rush

The Sourdoughs were not impressed as they downed their whiskey. They had heard Carmack’s tall tales before. Named for the fermented dough used to make bread and flapjacks, these men had drifted north while the rest of America had gone west. They barely peppered the interior of mammoth Alaska. The 1890 census showed Alaska with merely 4,300 whites. Along the Yukon River stretching out of the Canadian wilderness to the Bering Sea lived 2,000 Sourdoughs.

Still, Lying George was paying in raw gold, and it was about time for a strike. The value of gold shipped out of the Yukon Territory had jumped from $30,000 in 1887 to $800,000 in 1896 (roughly $771,000 to $23.3 million today).

A few days later, some 1,500 Sourdoughs decided to check out Carmack’s tale and made their way up the Yukon river to where the small Klondike tributary emptied into it. Each man hurriedly staked out a claim before the bitterly cold winter settled in. They threw up crude log cabins and shoved blocks of ice into holes in the walls to act as window glass letting light in and keeping the wind out.

Most of the Sourdoughs were destitute. Frank Buteau used sails to propel his sled as he was unable to afford a dog team. Paddy Meehan was molding dentures from tin spoons and using teeth from a mountain sheep for the fronts when a bear tried breaking into his cabin. After he shot the bear, he used the animal’s back teeth for the molars and then stewed and ate the bear with its own teeth.

By spring, each had a small fortune.

En masse, they made their way downriver to the Bering Sea, catching boats to the Lower Forty Eight, eager to spend their gold.

On July 14, 1897, the Excelsior docked in San Francisco, California, unloading the gold-bearing Sourdoughs onto an America stricken by one of its worse economic depressions. That year saw its highest unemployment rate since the panic started in 1893. A U.S. note could no longer be successfully redeemed for gold.

Three days later, the Portland docked in Seattle, Washington, with its Sourdough passengers. Roughly 5,000 people crowded the waterfront to see if the rumors of gold were true. They were not disappointed; Sourdoughs came running down the gang plank with bags of the glittering stuff.

In The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, reporter Beriah Brown flashed the nation with the news that the ship carried “more than a ton of solid gold” from the Klondike.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

A Crazy Seattle Scene

The announcement set off a stampede for the West Coast. Anything that could float was now sailing north out of Seattle. That city’s streets were jammed with thousands elbowing their way to the docks. Store clerks quit by the hundreds. Street cars halted as operators resigned on the spot. Hotels filled. Restaurants were packed with people. Seattle experienced an epidemic of dogs stolen and smuggled north to work the sleds.

Seattle Mayor W.D. Wood was attending a conference in San Francisco, California, when the Portland docked. He resigned by telegram and raised $150,000—more than $4 million in today’s dollars—to buy a steamer to take himself and paying passengers to St. Michael at the mouth of the Yukon River.

John McGraw, former Washington State governor and president of the First National Bank, hopped on the Portland northbound.

An elderly man fatally stricken with lung disease boarded the Portland, shouting at distraught relatives that he’d rather die trying to get rich than rot on his death bed in poverty.

Some 40 ships left for Alaska within the first months of the news of the gold strike. These included ships that, before the news, were scheduled to be broken up in the shipyards.

Celebrity Prospectors

Gold seekers could take two paths to the Klondike from Skagway and nearby Dyea. Roughly 40,000 prospectors chose the near vertical Chilkoot Pass, while others took the longer White Pass. Both trails met at Lake Bennett. There, Donald Trump’s grandfather, Friedrich Trump, operated a two-story hotel and restaurant that had a reputation of soiled doves for the offering.

Along the shoreline, 30,000 would-be millionaires waited for the frozen lake to snap open. When Lake Bennett did, on May 29, 1897, about 800 rafts set off on the first day; 7,124 boats, within 48 hours. All had to shoot through a series of rapids on the Yukon River. Mounties patrolled the rapids to recover the bodies of those who drowned, eluded forever from their fortune of gold.

Old West figures, including lawman Wyatt Earp, boxing promoter Tex Rickard and lawman Frank Canton, were drawn to the gold rush, as were madam Mattie Silks, poet scout John “Captain Jack” Crawford and Indian fighter “Arizona Charlie” Meadows.

Crawford, his goatee and long hair now snow white, sold ice cream out of the Wigwam, while Meadows impressed his saloon patrons by shooting little glass balls out of the hands of his dance hall girls, until the inevitable accident happened.

These famous pioneers mingled with throngs of inexperienced men and women—schoolteachers, single mothers, bank tellers, seamen, basketball coaches—staking everything on this one shot to get rich.

Sea captain Billy Moore, discoverer of the White Pass route, laid out Mooresville where the Skaguay River met the sea. But the crush of people overwhelmed him, and his mining claims were ignored. When the new city of Skagway platted a street through the middle of Moore’s home, the 74 year old came out swinging a crowbar before a mob subdued him.

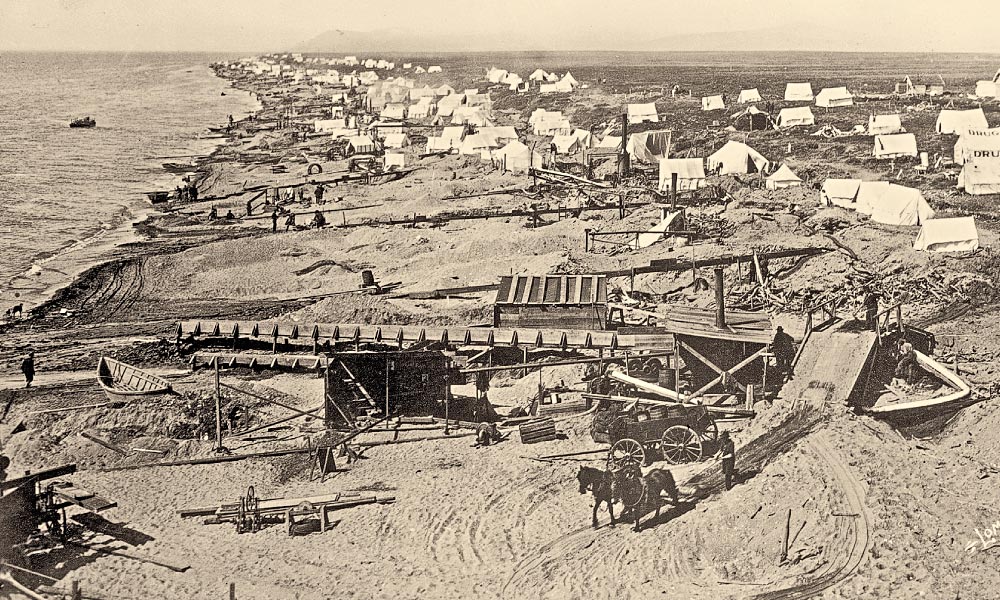

Young author Jack London found muddy streams serving as streets, lined with tents, huts and thrown up wooden structures. Gunfire filled the air, and prostitutes conducted business in full public view. North-West Mounted Police Superintendent Samuel Steele called Skagway “little better than a hell on earth.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The Rise and Fall

Established by Carmack’s gold discovery site, Dawson grew from 500 in 1896 to 5,000 within six months. By 1898, the city had 20,000 people. Of the 100,000 who set out for the Klondike, only 4,000 found gold. And only 200 found enough to be considered rich. Locals dubbed them the “Klondike Kings.”

A criminal element was drawn to these gold camps. Jefferson “Soapy” Smith led a vicious gang of confidence men, taking control of both Skagway and Wrangell, until gunfire brought an end to Soapy, literally.

In contrast, Dawson was relatively safe, with 288 Northwest Mounted Policemen under Supt. Steele. Gambling and prostitution were permitted, as law enforcement focused on major crimes. Not one murder took place in Dawson. Steele also enforced a series of blue laws that included one ensuring nobody worked on Sundays, or else, they’d have to chop firewood for the Mounties.

Genuine tales of wealth staggered the imagination. “Swiftwater” Bill Gates’s claim was literally knee deep in gold. Within two hours, Jim Tweed took $4,284 (roughly $160,000 today) from his claim. Frank Dinsmore found $24,489 ($722,000) in gold in one day. Albert Lancaster averaged $2,000 a day for eight weeks ($3.3 million). Sid Grauman saw his first movie in the Yukon; the money he and his father made entertaining the miners paid for their movie palaces in California, including the last one Sid built, the famous Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles. Tom Lippy became a philanthropist, giving generously to the YMCA and donating land to expand Seattle General Hospital in Washington. Lying George Carmack invested in Seattle real estate and died wealthy.

Dawson prostitute Silks made a fortune mining the miners; she returned to Colorado where she married a rancher. Lawman Rickard left Alaska with enough gold to acquire New York’s Madison Square Garden. Playwright Wilson Mizner helped build the Brown Derby into an iconic Los Angeles restaurant. Trump sold his hotel-restaurant in Whitehorse, returned to Germany to get married and then moved to New York, where his gold aided in real estate ventures.

Actresses “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, “Diamond Tooth” Gertie Lovejoy and “Diamond Lil” Davenport made huge sums. Grace Drummond sold herself to Charlie Anderson for $50,000 (nearly $1.5 million); Gussie Lamore joined Gates for $30,000 (valued today at $884,000), a price determined by her weight in gold.

Fate was not so kind to others. Charlie Anderson lost his fortune when a 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed his real estate holdings. When he died in 1939, he was pushing a wheelbarrow as a day laborer. Antone Stander built Seattle’s Stander Hotel before liquidating his fortune in alcohol. Pat Galvin lost his fortune buying riverboats that sank.

Within three years, the stampede had ended. A fire broke out on April 26, 1899, in a saloon, while the fire brigade was on strike, and burned down 117 structures. Word came of a new gold strike in Nome. Dawson became a shell of its former self.

The Klondike Gold Rush was over.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.