– Courtesy Lionsgate. –

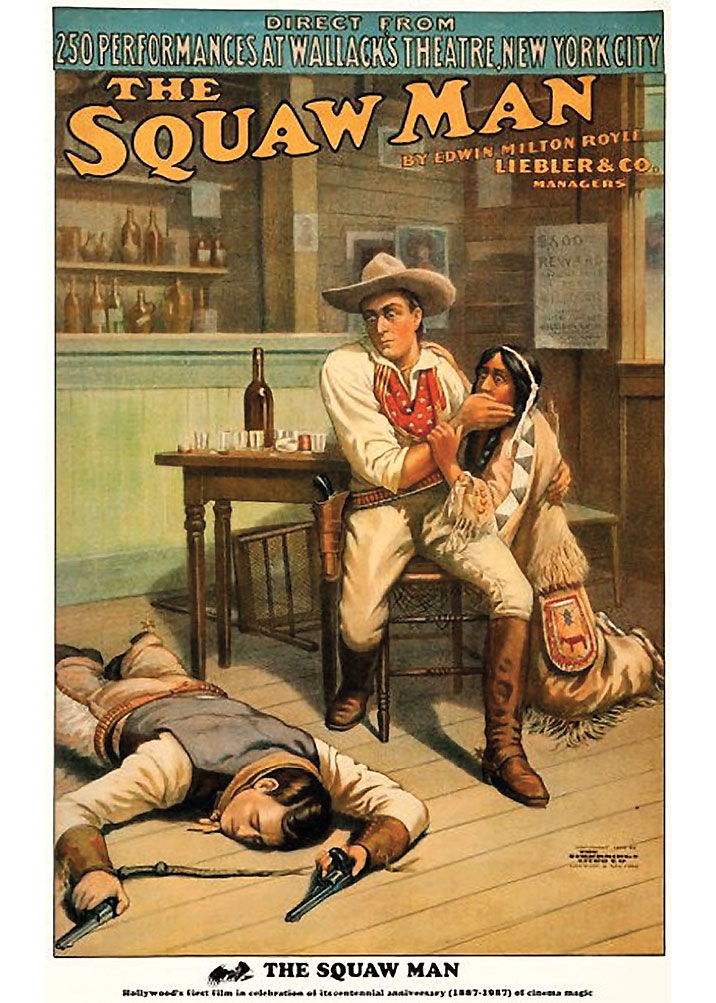

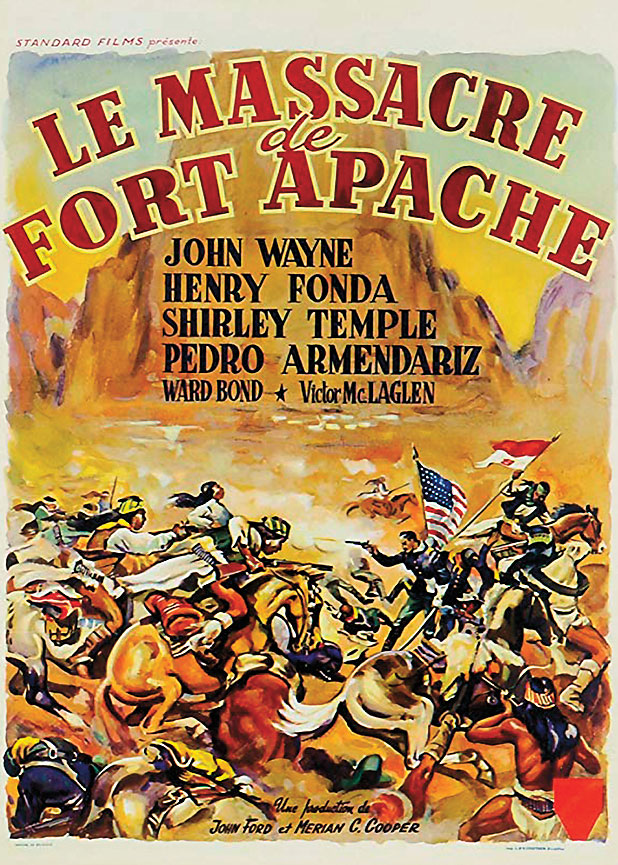

The very first feature-length movie made in Hollywood, Cecil B. DeMille’s 1914 film The Squaw Man, was an Indian-centered Western, and D.W. Griffith was making films like The Red Man’s View five years earlier. Whether factual or fantasy, Indian Westerns have a long, if checkered, history. The points of view run the gamut: when Francis Ford directed and starred in 1912’s Custer’s Last Fight, the Indians were portrayed as savages. When younger brother John Ford directed 1948’s Fort Apache, there was no doubt that Henry Fonda’s Custer character was the savage.

While early films tended to show Indians as the enemy both of whites and of progress, there were always sympathetic portrayals of Indians—whether as noble savages, childlike innocents or simply as human beings. More evenhanded treatment became the norm by the 1970s, not coincidentally concurrent with the rise of Indian activism. The American Indian Movement’s occupation of Alcatraz and Wounded Knee, and Marlon Brando’s refusal of his Godfather Oscar over Indian treatment in films, were initially greeted by the public with amusement or annoyance, but these actions forced a spotlight on the unfair treatment of Indians by various government agencies. Three of the most visible participants and spokesmen for the Movement would eventually become three of the most respected actors in the new wave of Westerns: Russell Means, Graham Greene and Wes Studi, who in October became the first American Indian to be awarded a career Oscar.

Social justice warriors might dismiss older films simply because the Indians were portrayed by non-Indians, but that would be foolish. The suddenly widely accepted idea that people should portray only their own ethnic/racial/sexual identity, is of very new vintage. Michael Horse, Yaqui and Apache, who played Tonto in 1981’s Legend of the Lone Ranger, Deputy Hawk in Twin Peaks, and is in the current Call of the Wild, reminds us, “The process of acting is to portray something that you’re not.” He adds, “But if you’re doing a cultural piece, and you don’t bring somebody who comes with that culture, you’re going to cheat yourself.”

Michael Dante, an actor of Italian descent, played many a cowboy in Westerns, but also played the son of Victorio, opposite Audie Murphy, in 1964’s Apache Rifles; Crazy Horse in the Custer TV series; and most famously starred as Winterhawk. “The problem in those days, there weren’t that many Native Americans that had a background in the theatre. They weren’t professionals; they weren’t given the opportunities.”

In the early days of the silent movie, indigenous people often portrayed themselves. In 1908’s The Bank Robbery, Quanah Parker, the last Comanche war chief, plays himself. In 1920’s The Daughter of Dawn, Quanah’s daughter Wanada, and son White, play lead roles. Shot in Oklahoma, the film tells the story of the struggles between Comanche and Kiowa, and tribe mem-bers make up the entire cast. Beginning her screen career in 1908, actress Red Wing was born on Nebraska’s Winnebago Reservation, and had appeared in over 60 films when she starred in DeMille’s The Squaw Man. Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance’s swoon-worthy physique made a powerful impression in the Paramount early talkie The Silent Enemy, and stardom seemed a real possibility. Tragically, when word leaked out that he wasn’t “pure” Indian, but part black, his career collapsed, and he committed suicide.

With the coming of sound, DeMille filmed The Squaw Man yet a third time, with Mexican actress Lupe Valez as the Indian girl. In 1934, Valez would star in the remarkable Laughing Boy, based on Oliver La Farge’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. The tale of a traditional Navajo lad (Ramon Novarro) who falls for “Americanized” city Navajo girl—and kept woman, Valez was so daring and controversial that director W.S. Van Dyke kept his name off of the credits.

– Courtesy Jesse L. Lasky, Feature Play Company. –

End of The Trail, released in 1932, was a B Western like no other. Tim McCoy, who’d lived on the Wind River Reservation, and was adjutant general of Wyoming before becoming an actor, plays Cavalry Capt. Tim Travers, who has made enemies at the fort for being an “Injun lover.” Framed for selling rifles to the Arapahos, he’s discharged from the service, but leaves only after giving a scathing speech denouncing the military and the government for not honoring any treaties made with Indians. Soon his son is killed by soldiers, he’s wrongly sentenced to death, and this is only partway through this unique 59-minute movie!

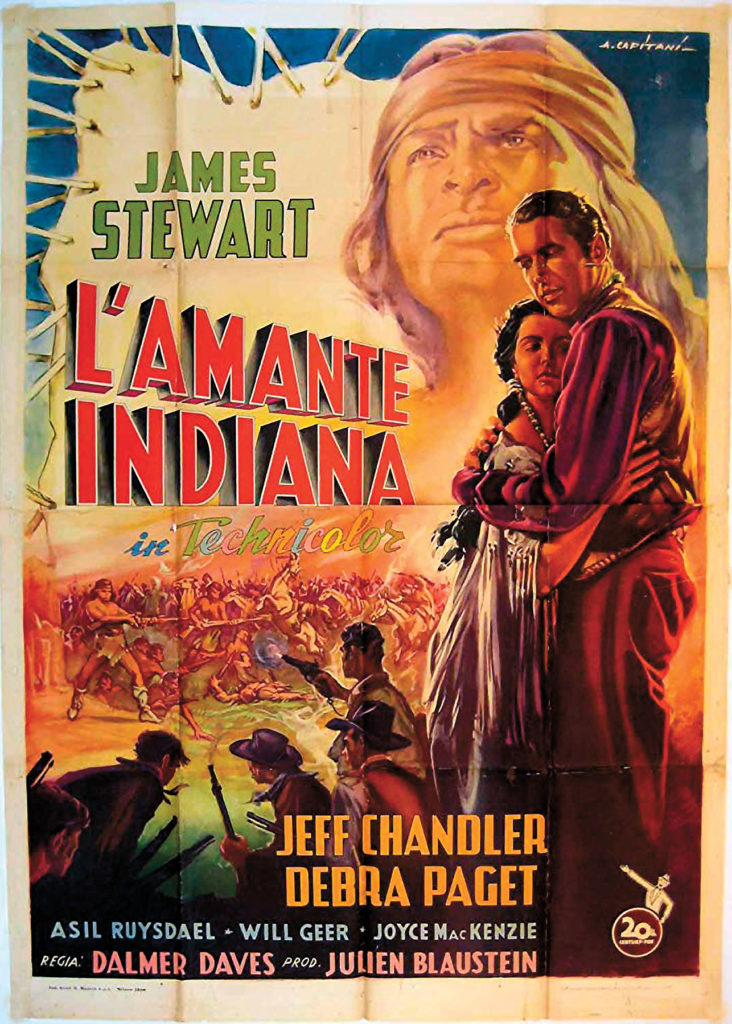

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s very few Westerns were built around Indian characters. Then came 1950, and Broken Arrow, director Delmer Daves’s largely true story of the peace negotiated between former Indian fighter Tom Jeffords (James Stewart), and the Apache Chief Cochise (Oscar-nominated Jeff Chandler). The honor and wisdom of the protagonists is striking. The unspoken irony is that the peace would not be honored by the government. Jay Silverheels took a break from The Lone Ranger to give a powerful though brief performance as Geronimo.

– Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. –

In 1954 Drum Beat, Delmer Daves’s story of the Modoc War of 1873, starred Charles Bronson as Kintpaush, the Modoc leader known as Captain Jack, opposite Alan Ladd as the frontiersman who’s trying to prevent further bloodshed. In addition to being brave and daring, Kintpaush has a sense of humor, and is more sophisticated than the ministers and generals he manipulates. Bronson’s parents came from Lithuania. Eastern Shoshone actor and stuntman Cody Jones,who has worked on The Son, Hostiles and the upcoming Outlaw Johnny Black, says, “At the end of the day, acting’s acting. Charles Bronson, he was good.” Michael Horse agrees. “Charles Bronson used to come pretty close.”

– Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox –

Also in 1954, Burt Lancaster played Massai, a warrior who breaks away from Geronimo rather than live on the Florida reservation, in Apache. While his and his woman Jean Peters’ pale blue eyes are distracting, it’s a fine film full of original scenes, like Massai’s first terrifying visit to a white mans’ town, and his meeting with a successful Cherokee farmer. Charles Bronson again excels as Hondo, a sell-out to the Army.

Among the “White Man Who is Made an Indian Because of His Bravery” films, the best is 1957’s Run of The Arrow, from writer/director Sam Fuller. Rod Steiger plays an ex-Confederate who runs afoul of the Sioux, and when he survives their ritual “run of the arrow,” is made a member of the tribe by Chief Blue Buffalo (yes, Charles Bronson). A fine successor, is Elliot Silverstein’s 1970 film A Man Called Horse. From the pen of Dorothy M. Johnson, whose other filmed stories include The Hanging Tree and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, it stars Richard Harris as a British aristocrat whose hunting vacation ends when he’s captured and enslaved by a Sioux raiding party. When he’s allowed to join the tribe, and marry, the enemies they must contend with are not other whites, but Seminoles, with jarring brutality on both sides. The rituals are historically documented, and unflinching, performed by Iron Eyes Cody. Cody himself is perhaps the best real-life example of tribe adoption. Beginning in silent Westerns in 1926, Cody became the screen’s foremost Indian actor, with more than 200 roles in his nearly 60-year career, best remembered as the Crying Indian in the famous anti-littering P.S.A. Most Indians were well-aware that Cody was in fact the son of Italian immigrants, but because he always portrayed Indians in an honorable and historically accurate way, they kept his secret from the general public until after his death.

– Courtesy National General. –

Horse’s screenplay was by Jack DeWitt, whose Westerns were revisionist long before the term was coined. In Sitting Bull (1954), starring J. Carrol Naish, DeWitt pulls no punches in his contempt for Custer. And he daringly includes a historically accurate but rarely seen black Sioux (Joel Fluellen), a former slave adopted by the tribe. In DeWitt’s The Battles of Chief Pontiac (1952), Pontiac (Lon Chaney, Jr.) must deal with English allies and their homicidal Hessian mercenaries. “The industry has needed a good Indian for years,” Chaney had said, “and I’d like to be it.” He would be that in 1956’s Daniel Boone—Trailblazer, and the following year in the Saturday morning series Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans, in which he played James Fenimore Cooper’s Chingachook to John Hart’s Hawkeye.

– Courtesy Warner Bros. –

Although the often-glacial pace requires as much patience from the audience as the Congress expected from the Cheyenne, John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn (1964) is a pro-Cheyenne telling of the Army’s attempt to force the Cheyenne from their homelands, to a reservation. Mad Magazine’s parody, Cheyenne Awful, features a background Indian commenting, “Notice how the director gave the five leading Indian roles to three Spaniards, an American and an Italian, while we real Indians play crummy extras!” To be fair to Ford, the three “Spaniards”—Dolores Del Rio, Ricardo Montalban and Gilbert Roland—were all Mexican by birth, and presumably of Indian as well as Spanish blood.

“Paul Newman nailed it,” Michael Horse says of his performance in 1967’s Hombre, Elmore Leonard’s Western take on J. M. Barrie’s The Admirable Crichton. Newman is the self-possessed white-raised-by-Apaches whose path crosses with a stagecoach full of “real” whites, including embezzling Indian Agent Fredric March and outlaw Richard Boone. Directed by Martin Ritt, the film makes social points that are organic yet startling.

– Courtesy National General. –

Michael Horse recalls, “Little Big Man was the first time I saw one of those funny old elders that I grew up with, and Chief Dan George was just magic. ‘Am I still in this world?’ ‘Yes, grandpa.’ Dustin Hoffman tells him, ‘I have a white wife.’ ‘Does she show enthusiasm when you mount her?’” Little Big Man (1970) is the story of the only white survivor of Custer’s Last Stand. A jarring mix of broad humor and horrendous slaughter, the brutality in the depiction of the Army, and Richard Mulligan’s portrayal of Custer as a preening halfwit, make it unforgettable.

In Chato’s Land (1972), all Charles Bronson’s half breed Chato wants is to enjoy a drink at the saloon, but when a lawman gives him no other choice, Chato kills him. A posse pursues him into the desert, not realizing they’ve become Chato’s quarry. With almost no dialogue, performing almost entirely alone, Bronson gives a calm dignity and perseverance to his character.

– Courtesy ABC Television. –

In David Wolper and Stan Margulis’s 1975 Emmy-nominated production I Will Fight No More Forever, the unpunished murder of an Indian by a white begins an unwanted war. Famed one-armed Gen. Oliver O. Howard (James Whitmore) is ordered to force the Nez Perce onto a reservation. Chief Joseph (Ned Romero) befuddles the general with his superior tactics, keeping his tribe one step ahead of the Army for over a hundred days, nearly reaching Canada before surrendering with the words that are the film’s title. Written by Jeb Rosebrook and Theodore Strauss, the TV movie features a young Sam Elliott as Indian-sympathetic Capt. Charles E.S. Wood.

– Courtesy Columbia Pictures. –

In 1975, independent rural filmmaker Charles B. Pierce wrote and directed Winterhawk. When a Blackfeet village is struck with smallpox, Winterhawk (Michael Dante) goes to a mountain man rendezvous to trade pelts for medicine, but is instead bushwhacked and robbed by badman L.Q. Jones. Winterhawk captures a sister (Dawn Wells) and brother to trade for medicine. Notable for its cast, the pursuers are Leif Erickson, Woody Strode, Denver Pyle and Elisha Cook Jr. Dante notes, “When you’re playing a Native American, you have to speak with your hands in the dirt psychologically, to relate to the moon, the wind and stars, the elements, the environment. They’re very spiritual. He was not written as a spiritual man. I brought that.” It was the last time Dante would play an Indian. “Now they won’t hire a white man. They don’t need to; they have a lot of wonderful actors. Graham Greene, Wes Studi, Zahn McClarnon, Adam Beach—he’s an outstanding actor.” Dante was delighted to learn that one of his favorite current actors made his first visit to a set on Winterhawk. “I grew up in Montana,” says Longmire’s Zahn McClarnon. “They were looking for extra women. My mom is this gorgeous Lakota woman, and she went onto the set to be an extra. And I met Woody Strode. I was like six or seven, I wouldn’t go ask for his autograph. But I finally got the nerve to.”

– Courtesy Warner Bros. –

What are some of McClarnon’s favorite Indian films? “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Josey Wales.” Cody Jones concurs. “Clint Eastwood used Chief Dan George in Outlaw Josey Wales, that’s one I enjoy a whole lot. Even today, the image of the Native is the great warrior of the plains, the stoic. But reality is, American Indian culture has a lot of laughing. And Will Samson: big guy, big presence. It was awesome to see Clint bring the natives into the forefront like he did.” At least the first half of Josey Wales, one of Eastwood’s best films, is about a farmer seeking revenge on the Union soldiers who slaughtered his family. But it’s the humor and the humanity that stays with you.

In Legend of Walks Far Woman (1982), Raquel Welch’s character, banished by her Blackfeet tribe, tries to make a life with her mother’s Sioux people. This is a woman’s story full of unusual situations, like dealing with her husband after a concussion suffered at the Little Bighorn makes him violent. The only whites seen are the dead cavalrymen whose pockets are emptied.

– Courtesy Orion Pictures. –

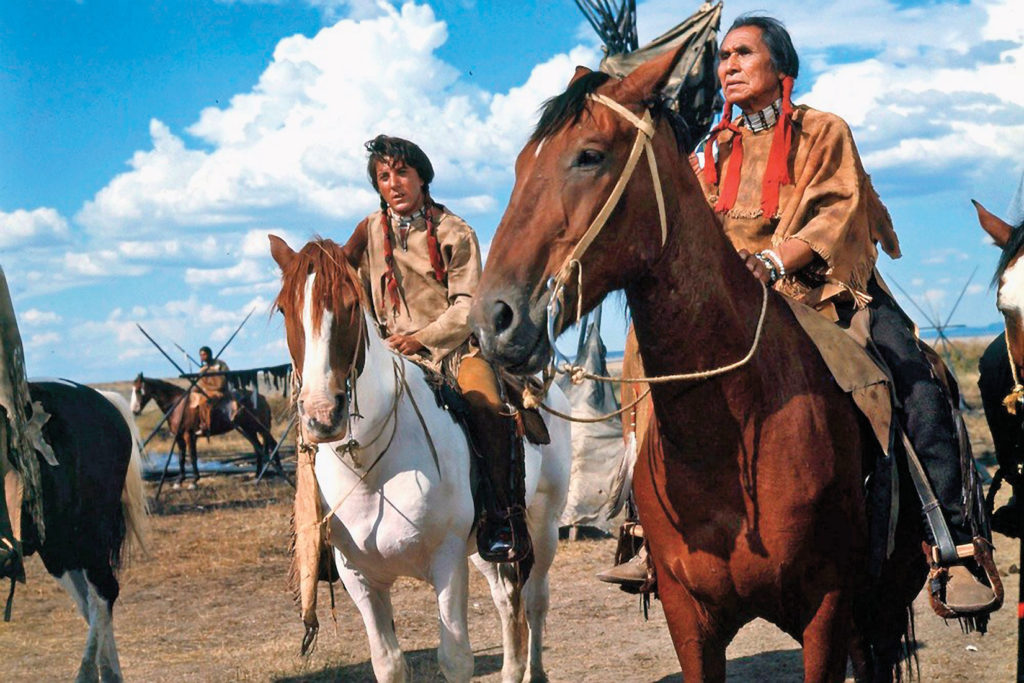

Dances with Wolves (1990) was the game changer. In addition to being an excellent film, and an astounding first-time directing effort by Kevin Costner, no other film had ever given so many major roles to Native actors: Graham Greene, Rodney A. Grant, Floyd “Red Crow” Westerman, Tantoo Cardinal, Wes Studi and nearly a dozen others. The Last of the Mohicans (1992) continued the same trajectory. Michael Mann’s film, the ninth version in America alone, starred Daniel-Day Lewis, Madeleine Stowe and Wes Studi, and introduced many audiences to Russell Means and Eric Schweig. Both films combine thrilling romance and action, compelling characters, and seemingly doomed civilizations. They are both beautifully made films. Mohicans made a fortune, and Wolves is the most successful Western of all time.

– Courtesy HBO. –

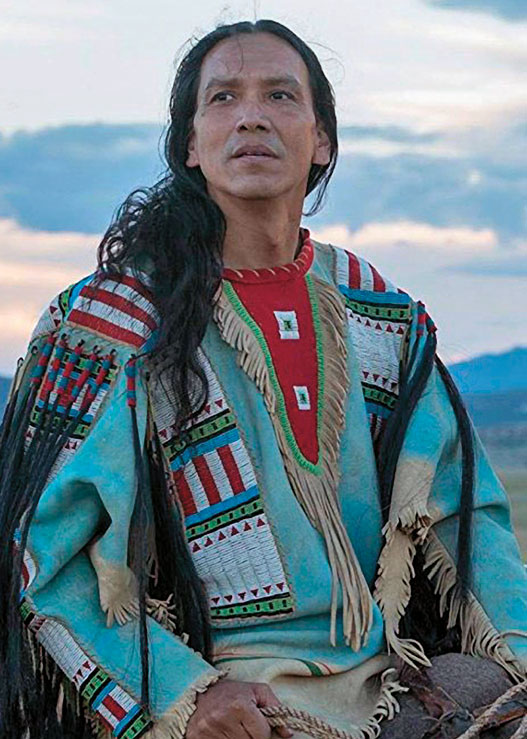

Geronimo—An American Legend is the 1993 masterpiece of director Walter Hill, writer John Milius, and star Wes Studi. A lavish war movie as well as a Western, it follows Geronimo from his surrender to the Army, to his followers’ and his own mistreatment, to his escape to Mexico, and beyond. The problems of the chain of command are highlighted, as Geronimo puts his faith in General Crook (Gene Hackman), and Lieutenant Gatewood (Jason Patric), whose actions are controlled from Washington.

– Courtesy Black Bicycle Productions. –

Unlike Chief Joseph, Sitting Bull and his Lakota followers did manage to reach Canada, but not for long. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, the heartbreaking 2007 TV movie, is seen largely through the eyes of Charles Eastman (Adam Beach). As a Sioux child he’s taken from his parents, and sent to a school to be Americanized: his hair cut, his clothing replaced, forbidden to use his native language, he’s even forced to take on a Christian name. But when the educators see how bright he is, he’s sent to college and medical school, used as a PR tool by the government, and finally returns to Standing Rock, where he tries desperately to fit in, and to save his people.

– Courtesy Lionsgate. –

In the past couple of years, there have been two impressive Indian-centered Westerns. Hostiles stars Wes Studi as a long-imprisoned Cheyenne Chief finally allowed to return to his ancestral home. Christian Bale is the Indian-hating Army captain who reluctantly agrees to escort him. It feels spiritually like a continuation of Studi’s earlier Geronimo. Woman Walks Ahead stars Jessica Chastain as Catherine Weldon, a New York painter who journeyed out west to paint a portrait of Sitting Bull (Michael Greyeyes), and becomes involved in the Sioux battle to protect their land.

Henry Parke is True West’s Western film and television editor. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year. If we missed any of your favorite Indian Westerns, please share them with us. If you’d like to read more of Michael Dante’s interview and Henry’s columns on Western film and television, go to TrueWestMagazine.com and subscribe for full access to True West’s Archives.