— All Images Courtesy United Artists Unless Otherwise Noted —

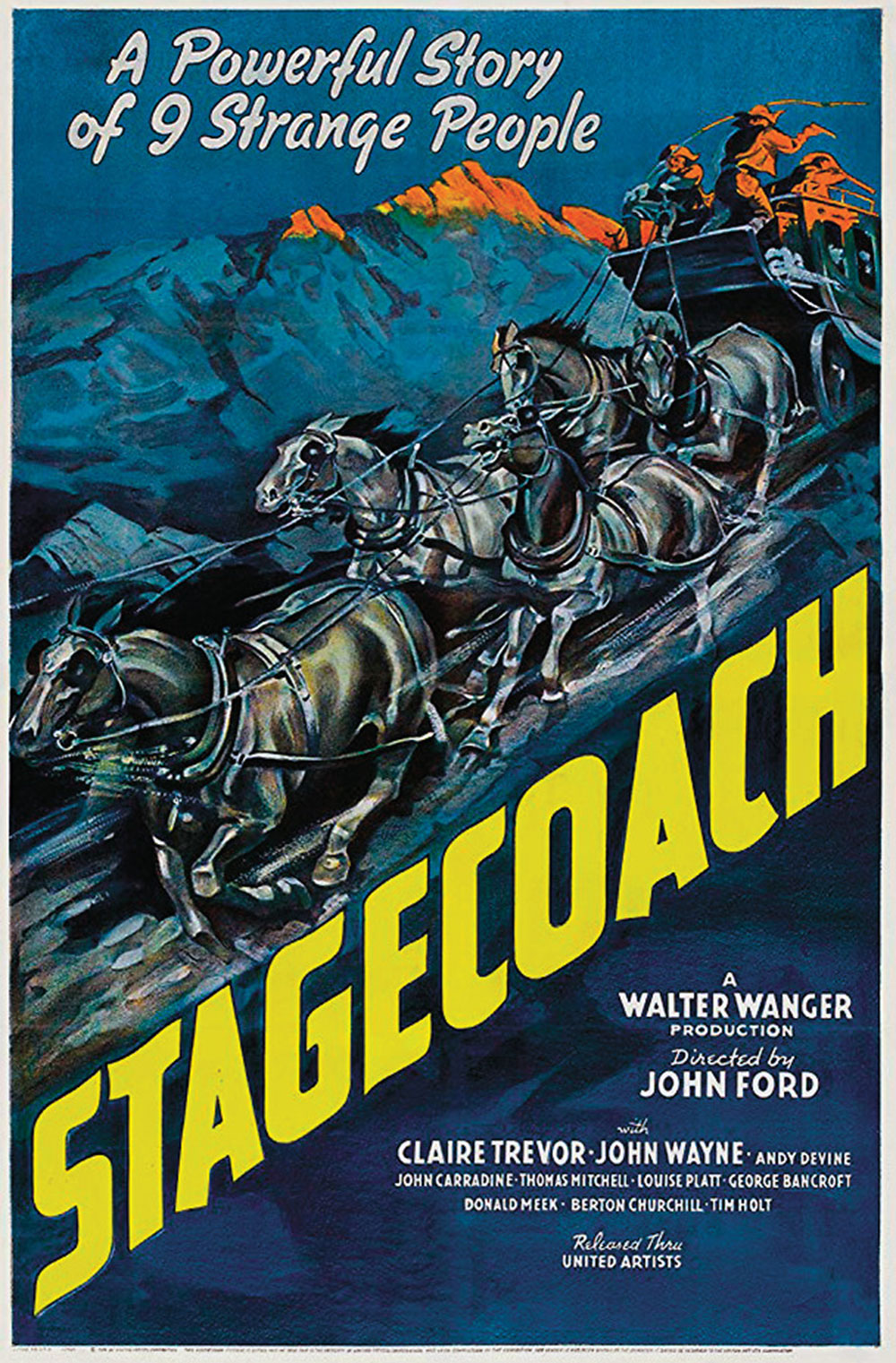

Eighty years ago, director John Ford and screenwriter Dudley Nichols combined their talents, and those of star character-actors Claire Trevor, Thomas Mitchell, John Carradine and newcomer John Wayne, and made Stagecoach, a movie that would forever alter Western film history. It’s been called the Citizen Kane of Westerns—ironic, since Stagecoach preceded Kane by two years. Yet it’s an apt comparison, because those films changed the future of movies, not by an innovation easy to point out, like Technicolor or 3D, but by utilizing all of the aspects of the filmmakers’ arts to tell stories perfectly.

John Ford had been directing films since 1917, beginning with the silent Western three-reeler, The Tornado, and had made nearly 60 Westerns since then. In 1939, with his first of four Oscars under his belt for 1936’s The Informer, he could work anywhere he wanted, with studio bosses like Daryl Zanuck and David O. Selznick happy to bankroll any project he’d like. Only now he wanted to make a Western, a genre he hadn’t touched in 13 years, since his silent hit 3 Bad Men, which he would remake in 1948 as 3 Godfathers.

Dan Ford, John Ford’s grandson, says, “He always preferred to work from shorter projects and expand them, rather than work from novels and cut them down. A lot of his movies came from The Saturday Evening Post or Colliers magazines.” Ford’s son Patrick had read the Ernest Haycox story Stage to Lordsburg in Colliers, and told his father it might make a good movie.

Rarely read today, Haycox was a very popular, very driven Western author in his day, who started in the pulps but, as Haycox biographer Richard Etulain puts it, “took the Western out of the ‘pulps’ and took it into the ‘slicks’,” that is, higher-quality magazines printed on smoother paper. Growing up poor in Oregon, Haycox, like so many of his characters “had hardscrabble origins. He’s virtually an orphan by the time he’s 10, out on the street, selling newspapers.” In his mid-teens he lied about his age to join the Army, and fought under Pershing against Pancho Villa on the Mexican border. He fought in World War I, then graduated from The University of Oregon in 1923 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. Ernest Hemingway once noted, “I read The Saturday Evening Post whenever it has a serial by Ernest Haycox.”

The premise of Haycox’s story is simple: a group of strangers boards a stagecoach to Lordsburg, and a series of unexpected challenges, including an attack by Apaches, reveals who rises to the occasion, and who does not.

The usual price for film rights to a Colliers story was $1,100, but Ford paid $2,500 for Stage to Lordsburg. When he tried to set it up at a studio, Ford came up against two powerful objections: it was a Western, and he insisted on casting an unknown in a pivotal role. The once-popular Western genre had fallen out of favor, except with rural and juvenile audiences. In 1930, Fox had spent $2 million making a Western epic, The Big Trail, shot in a new process called Grandeur. Unfortunately, during the Great Depression, exhibitors who had just spent a fortune converting their theaters to play “talkies” had no interest in spending another fortune to convert to wide-screen. Except for in a handful of theaters, the movie played in standard, square 35mm, and it bombed.

The virtually unknown actor Ford wanted to feature was a former college athlete and prop man who had accidently wandered into a scene Ford was directing, startling Ford with how photogenic he was. He was groomed by Ford, given small bits in films until he suddenly got a big break and was cast as the lead in The Big Trail. His name had been Marion Morrison, but they’d changed it to John Wayne. And now Ford wanted Wayne to star in Stagecoach.

“I don’t think anybody blames a $75-a-week actor when a $2 million picture goes down in flames,” Ford and Wayne biographer Scott Eyman points out. But Wayne had begun starring in B-Westerns and he was “damaged goods as far as they were concerned. After you failed at Fox, you were exiled to Monogram and Republic, and you never got back. It was like Devil’s Island.” Wayne would star in 33 B-Westerns in nine years, until John Ford called. He never did a B-picture again.

Selznick was willing to produce the film, but he wanted stars with big enough names to ensure a profit. Why not Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich, instead of Wayne and Trevor? Even though Claire Trevor had been Oscar-nominated in 1937 for Dead End (she’d win in ’48 for Key Largo), she was seen as a B-movie star. But Ford held firm, and the film was eventually put together, Ford’s way, with independent producer Walter Wanger at United Artists.

Dudley Nichols had won an Oscar for The Informer, and would collaborate with Ford on 16 movies. What he did so masterfully in adapting Stage to Lordsburg was to add urgency, to up the ante for the characters, making them individuals instead of types. No longer just a gambler, John Carradine’s character is a ruined Southern gentleman hiding his shame, and eager for a chance to regain his dignity. The Army Girl (Louise Platt) is no longer going to meet her fiancé; she is now Mrs. Lucy Mallory and married to an officer, and about to give birth. Thomas Mitchell’s character is no longer just a drunk; he’s a drunk doctor, and will have to deliver Mrs. Mallory’s baby. Malpais Bill, now the Ringo Kid, is still on his way to Lordsburg for revenge on Luke Plummer, played by Tom Tyler, but now Ringo is an escaped convict, and the sheriff (George Bancroft) is along for the ride. Henriette, now Dallas, would never tell Ringo, as in the short story, “I run a house in Lordsburg.” Her greatest fear is that he will learn this about her. Now the whiskey drummer (Donald Meek) survives, the Englishman is dropped, the cattleman is turned into the embezzling banker (Berton Churchill). About the only character that hardly changes is the driver, Happy, now Buck portrayed by Andy Devine, becomes that much more of a welcome comedy relief figure.

When John Wayne came over from Republic, he brought with him Yakima Canutt, arguably the greatest stunt man who ever lived. Most of the convincing fight scenes performed in films since the mid-1930s are based on techniques Canutt and Wayne developed while working together on poverty row.

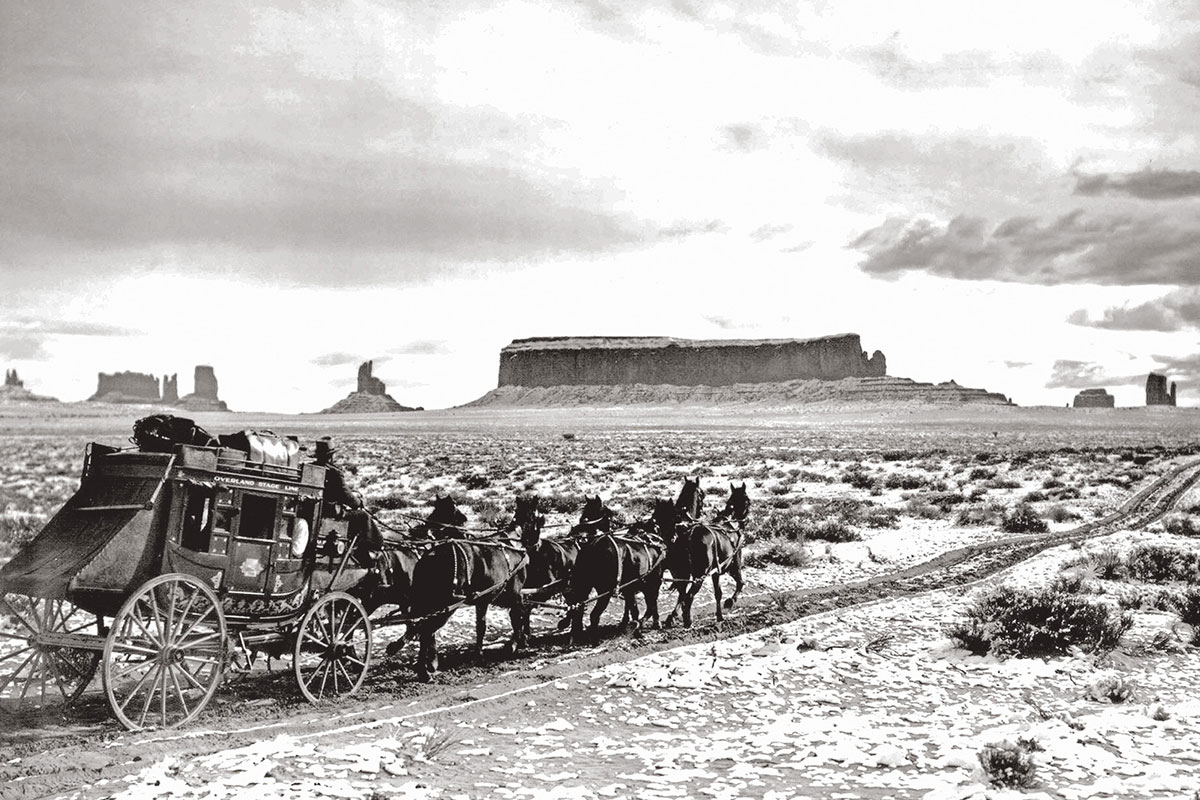

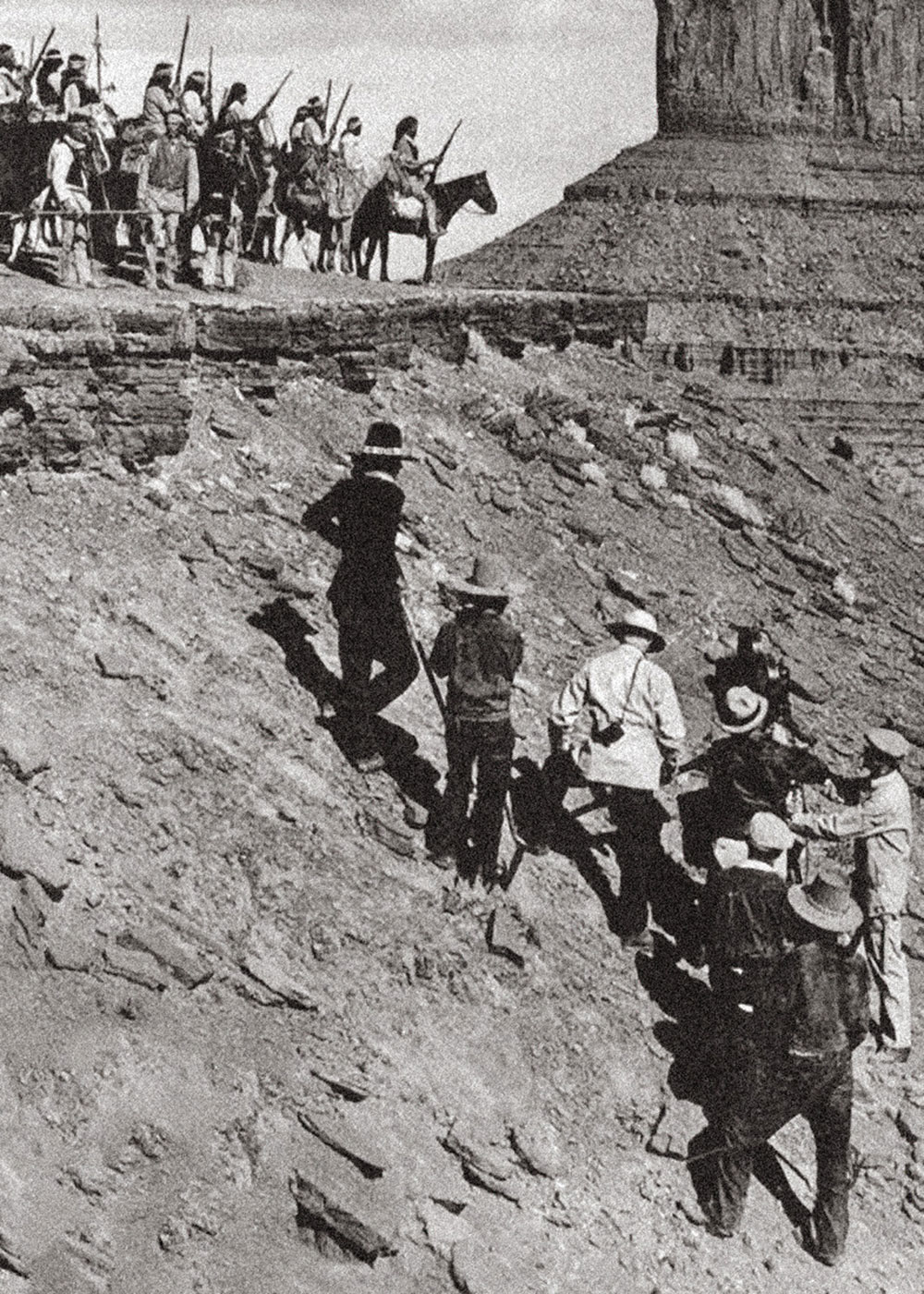

The exterior stagecoach shots were filmed first, in what would become John Ford’s personal trademark, Monument Valley. The exteriors for the opening town of Tonto and closing town of Lordsburg were both shot at Republic Studios. The end was originally planned for daylight, but was changed to night to hide the fact that it was the same town, and the night-for-night photography is wonderfully pre-noir noir.

One of the key sequences, where the stage stop is found burned to the ground, and a river must be crossed to escape the Apaches (played by Navajos), was filmed on the Kern River.

The climactic chase, with Apaches tearing after the coach, was shot over three days at Mojave Desert’s Lucerne Dry Lake Bed, where Ford had previously filmed the land rush sequence for 3 Bad Men. The chase is an astonishing collaboration of the skills of Ford and Canutt.

— Courtesy 20th Century-Fox —

The film was completed for just under $550,000, four days over the 43-day shooting schedule. Ford was paid $50,000, less than his then-current rate. Trevor, at $15,000, was the highest-paid cast member, with Wayne, at $3,700, the second lowest, making $34 more than Carradine.

The aftermath of Stagecoach is well known. It made John Wayne a star. Wayne and Ford would have a legendary collaboration on a dozen more films, some of the most highly regarded movies in film history. Grandson Dan Ford reveals another outcome of the success. “It was important to [Ford] because he had a big piece of Stagecoach, a big money-maker, and it sustained his family for the war years, so he could go off in the Navy.” Ford, who saw trouble coming earlier than most Americans, enlisted before the Pearl Harbor attack and went overseas, often handling cameras on the front lines. He achieved the rank of Rear Admiral and made about a dozen military films, covering subjects as varied as The Battle of Midway and sex hygiene.

— Courtesy The Weinstein Company —

Claire Trevor had a splendid career as a leading lady in A movies, and a long and happy marriage. Thomas Mitchell had an unbelievable 1939, starring in not only Stagecoach, but Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Gone With the Wind. He won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Stagecoach, and receiving the award, commented, “I didn’t think… I didn’t know I was quite that good.”

It was also a wonderful year for Ernest Haycox. In addition to Stagecoach, his novel Trouble Shooters became Union Pacific, directed by Cecil B. deMille, and starring Joel McCrea and Barbara Stanwyck. He was brought out to Hollywood to be a screenwriter, but didn’t care for it, and soon returned to Oregon, where he wrote successful novels and over 300 short stories. Seven movies were made from his stories in his lifetime. He died at the age of 51 in 1950, and his widow lived a comfortable life licensing his stories to films and television, and reportedly watched endless hours of Western TV to make sure his stories weren’t being used for free.

Considering how successful Stagecoach was, and how inexpensive shooting endless stagecoach interiors is, it’s surprising it hasn’t been more frequently imitated. But what it requires is great writing and great acting, and that’s rarely cheap. In 1951’s Rawhide, Tyrone Power and Susan Hayward are menaced at a stagecoach stop, which certainly has similarities to Stagecoach, as do virtually all of the Randolph Scott/Budd Boetticher films of the 1960s.

Other influences are not so obvious. Eyman asks, “Would Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat exist without Stagecoach? [It’s] Stagecoach on the water, basically.” To be fair, others have claimed that Stagecoach is just Grand Hotel on wheels, but of course, without Apaches.

On television, the economy of the set-up inspired episodes of many series, including The Rebel, Cheyenne and The Rifleman. In fact, Quentin Tarantino explained to Deadline Hollywood that these cut-rate Stagecoaches, particularly The Virginian, Bonanza and The High Chaparral, were his inspiration for The Hateful Eight. “Twice per season, those shows would have an episode where a bunch of outlaws would… come to the Ponderosa, or go to Judge Garth’s place… and take hostages. There would be a guest star like David Carradine, Darren McGavin, Claude Akins, Robert Culp, Charles Bronson or James Coburn. I thought, ‘What if I did a movie starring nothing but those characters? No heroes, no Michael Landons. Just a bunch of nefarious guys in a room, all telling backstories that may or may not be true. Trap those guys together in a room with a blizzard outside, give them guns and see what happens.’” In 2018, the final segment of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, “The Mortal Remains,” is an even more direct descendent of Stagecoach.

— Courtesy CBS Television —

Then there were the remakes. In 1966, 20th Century-Fox released its new take on Stagecoach, directed by Gordon Douglas, who’d started directing Our Gang comedies, and helmed highly regarded Westerns like Rio Conchos (1964). Ann-Margaret is Dallas, Alex Cord is Ringo, with Oscar-winner Red Buttons filling in for Donald Meek, Mike Connors for Carradine, Bing Crosby for Mitchell, and Slim Pickens for Andy Devine. Fox’s executives spent money on this one: the action is longer and bloodier, the locations are beautiful, and they even commissioned Norman Rockwell to paint one of the handsomest movie posters ever made. They made a film that’s adequate if you haven’t seen the original, but tedious if you have.

And perhaps the studio bosses knew it. As Pauline Kael noted, “Probably in no other art except movies can new practitioners legally eliminate competition from the past. A full-page notice in Variety gave warning that 20th Century Fox…“would ‘vigorously’ prosecute the exhibition of the 1939 original… one of the most highly regarded and influential movies ever made.” Or as John Carradine told Hollywood Snapshots author Michael B. Druxman, “They deserved to lose their shirts on the remake. Nobody could have been better than John Wayne, Berton Churchill, Thomas Mitchell or me. Great classics should never be remade.”

The 1986 version of Stagecoach is far worse, sadly, as it might have been wonderful. Starring Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, it was planned as a musical, with songs by Willie Nelson. Then half the budget disappeared, and except for the theme by Nelson, the music was never recorded. Kristofferson remembers, “It had a lot of trouble getting started, and we ended up in the stagecoach for most of it.” A brief appearance by Lash LaRue toward the end was the only link to a real Western.

Claire Trevor told Druxman, “Stagecoach was the only thing I’ve ever done that couldn’t have been done in another medium. It used the motion picture camera and music, folk songs with symphonic arrangements, that, up to that time, had never been done before.” She said it best.

True West Film Editor Henry C. Parke, namesake of his grandfather who, like Ernest Haycox, fought with Black Jack Pershing against Pancho Villa, recently did audio commentary on the Signal One Blu-ray of the 1966 Stagecoach remake.