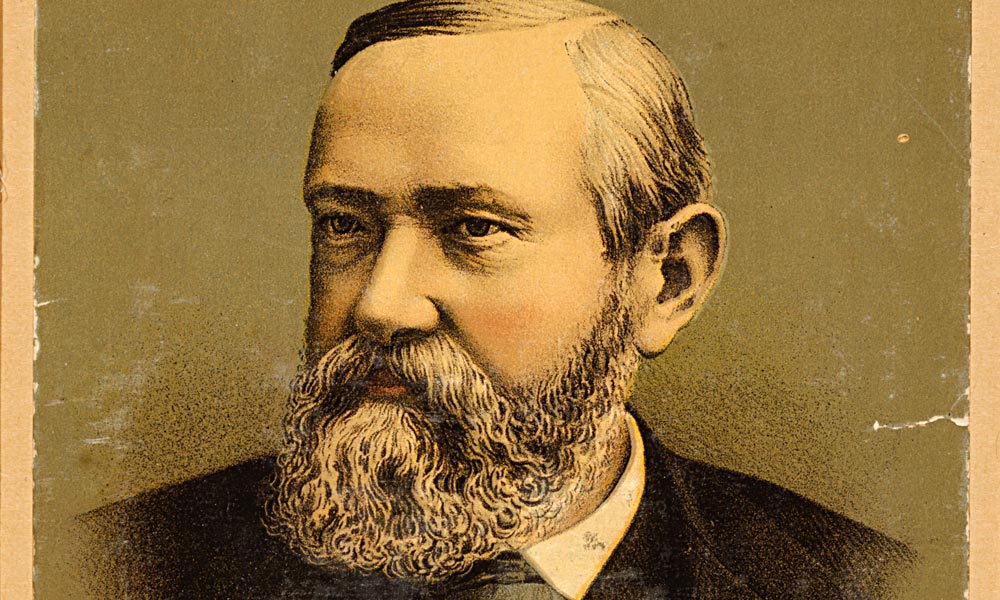

– Harrison photo courtesy library of congress; invaders photo Courtesy Wyoming State Archives, 21993 –

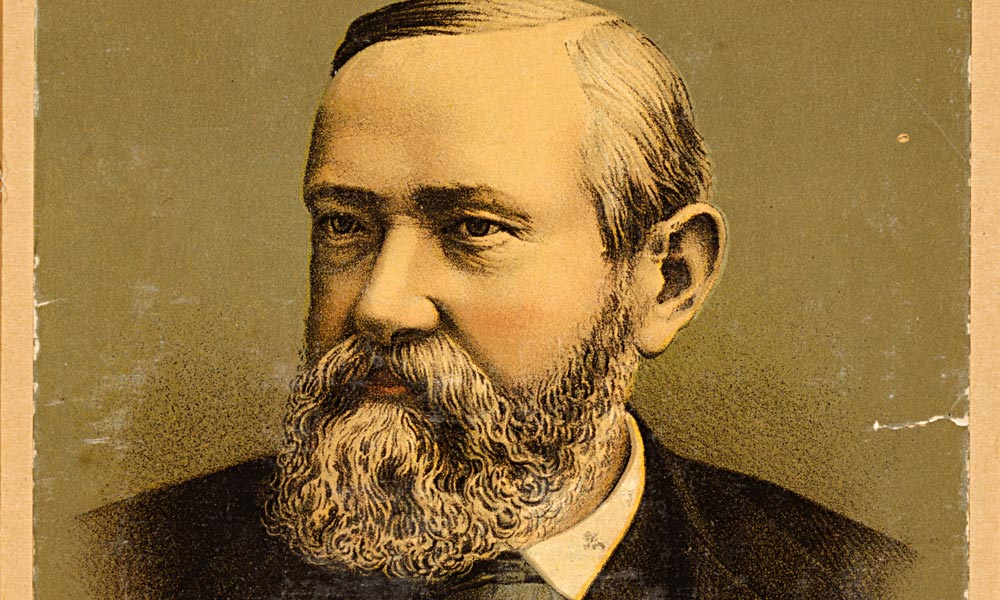

In April 1892, Benjamin Harrison had almost finished his first term as President of the United States. He couldn’t have foreseen it, but he was about to get pulled into the middle of Wyoming’s Johnson County War.

In the solidly Republican state of Wyoming, admitted to the union under the President in 1890, Harrison counted among his friends political leaders who had ties to big cattle operations. But historians doubt the President knew cattle barons were planning an invasion of the state. Their intent: to wipe out small ranchers whom they considered rustlers and nesters.

About 50 invaders first hit the KC Ranch on April 9, 1892, killing Nick Ray and Nathan Champion. The “army” was on the move until Johnson County Sheriff “Red” Angus and a posse that grew to roughly 400 men headed them off at the TA Ranch on April 10.

Cornered in a barn, with no water or food or additional ammunition, the invaders suffered a siege that went on for more than a day, until a smuggled message got through to state officials in Cheyenne.

Governor Amos Barber was shocked. The surgeon for the Wyoming Stock Growers Association prior to becoming governor, Barber had tacitly approved the invasion prior to its start. Now everything was falling apart.

Barber’s telegram to President Harrison began, “An insurrection exists in Johnson county, in the State of Wyoming, in the immediate vicinity of Fort McKinney, against the government of said state.”

His message didn’t state who was behind the insurrection. But it alarmed Harrison, who got the telegram at around 11 p.m. on April 12. He ordered Fort McKinney’s troops to intervene; they did, just before seven the next morning. Soldiers captured the invaders and took them to Cheyenne for trial.

Wyoming leaders—political and cattle—were nervous. Court testimony might implicate them in the affair, and the small ranchers who had fought the invaders might get the upper hand in the power struggle.

Violence continued, on both sides. Governor Barber and the state’s two senators pushed the President to declare martial law, which would effectively return power to the cattlemen.

But Harrison was reluctant. He now understood the situation and knew that many citizens supported the small ranchers. He also didn’t want to light a political powder keg, as he sought to keep his job. Harrison declined the request, although he did send 600 soldiers to Johnson County as a show of force.

The end of the affair was anticlimactic. Charges against the invaders were dropped; their power and money proved too much for Johnson County’s budget. Still, Wyoming Republicans lost state and local elections in November, mostly due to public reaction to the invasion. Harrison’s economic policies at the White House had been a disaster. He lost his re-election bid too and returned to Indianapolis and his law practice.