— Courtesy Library of Congress —

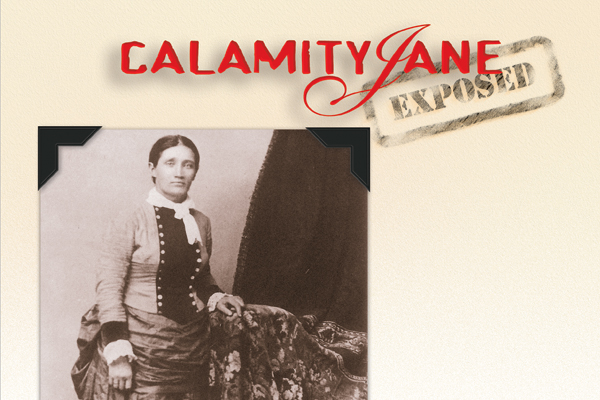

Born in Missouri in 1856, Martha Canary came west with her family, spent part of her childhood in the Montana goldfields near Virginia City and Nevada City, came of age, most likely in Utah, following the death of both parents (her mother in Montana, her father in Utah).

She struck out alone, leaving behind at least two siblings, may have spent time in southwestern Wyoming around Fort Bridger, and in 1869 was in the coal-mining/railroad town of Piedmont, in extreme western Wyoming. Then she worked her way east to Cheyenne.

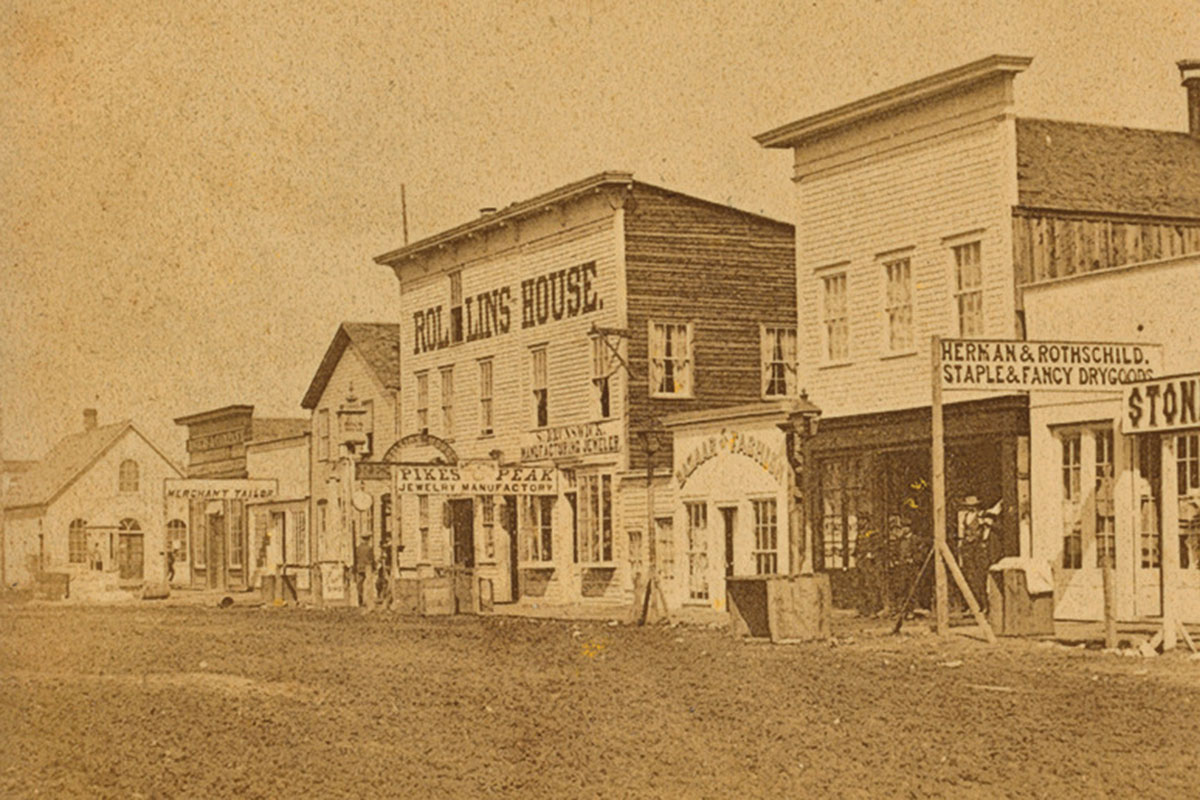

Started as an end-of-tracks town by the Union Pacific Railroad, Cheyenne was the Territorial Capital of Wyoming by the time Martha arrived in the early 1870s. The Territorial legislature in 1869 granted suffrage to women, along with the right to hold office and serve on juries. It was also becoming a cowboy capital serving cattle trails from Texas pushing herds onto the northern plains, and it had a military presence following the establishment of Camp Carlin (later named Fort D.A. Russell).

Calamity in Cheyenne

— Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism —

Cheyenne is a good place to begin tracing the life of Martha Canary. I recommend an overnight at the Nagle Warren Mansion Bed and Breakfast, once the home of a cattle baron in the days when Martha Canary was first in Cheyenne. Take time to visit the Old West Museum at Cheyenne Frontier Park, and the Nelson Museum downtown before heading out of town toward Fort Laramie.

The Cheyenne-Deadwood Trail came to quick prominence after men traveling with Lt. Col. George A. Custer found gold in the Black Hills in 1874. Like others in the region at the time, Martha Canary traveled the first leg of its route from Cheyenne to Fort Laramie. For a time she had worked six miles west of Fort Laramie at the road ranch operated by Adolph Cuny and Julius “Jules” Ecoffey. According to trader John Hunton and Sgt. John Q. Ward, for a time Canary also worked at a road ranch near Fort Fetterman.

Exactly when she came by the moniker Calamity Jane isn’t certain, but men along the rail line, and in the military, knew her as Calamity in the 1870s. She was at Fort Laramie in 1875, when the Black Hills Expedition was organized under the direction of Walter Jenney and Henry Newton. That party was charged with determining the quality and quantity of gold in the Black Hills.

On to Fort Laramie

— Courtesy NYPL Digital Library —

Our route takes us from Cheyenne to Fort Laramie by following Highway 85 to Torrington and then turning west on U.S. highways 20-26 to the town of Fort Laramie, and then west to Fort Laramie, now a National Historic Site.

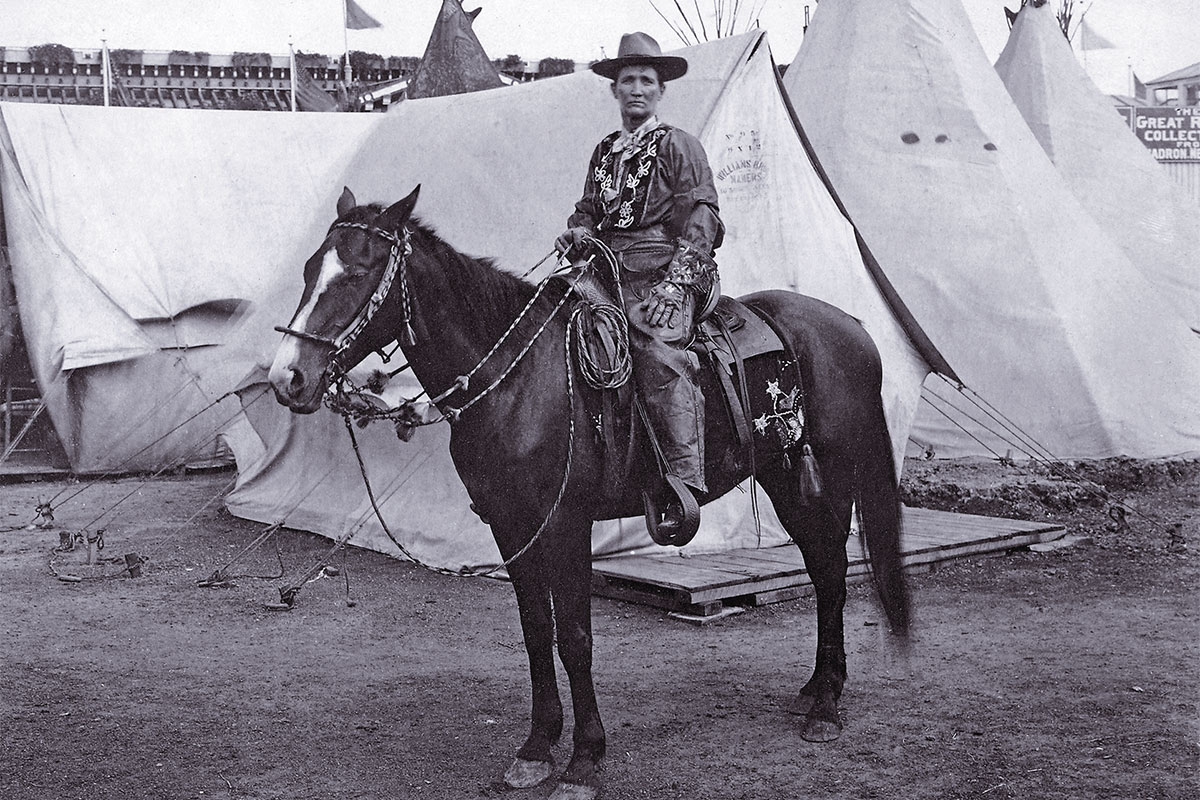

A member of the scientific party that explored the Black Hills in 1875, Valentine T. McGillycuddy first saw Jane, wearing spurs, chaps and a sombrero, on May 20, 1875, as she crossed the parade ground at Fort Laramie. When McGillycuddy, a surgeon who served as a cartographer for the Newton-Jenney Expedition, asked about the woman, Col. Hesnry Dodge identified her as a “regimental mascot” who “didn’t know the meaning” of the word morals.

But Calamity gave McGillycuddy advice after some of the soldiers pulled a prank on him, and the two became friends. She pressed McGillycuddy to put in a word on her behalf with Colonel Dodge to be allowed to accompany the expedition into the Black Hills, but the doctor-topographer declined. However, as he later wrote, when the march north began, an “unaccounted for young private” trailed in the expedition’s wake. That “private” was soon identified as Calamity Jane. She worked with the civilian teamsters and retained her tenuous position with the expedition, having made quite an impression on most of the men.

the WPA in the 1930s.

— Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism —

One description of her on that trip came from Acting Assistant Surgeon J.R. Lane who provided an account published in the Chicago Tribune on June 19, 1875. “Calam is dressed in a suit of soldier’s blue, and straddles a mule equal to any professional blacksnake swinger in the army,” Lane wrote. “Calamity also jumps upon a trooper’s horse and rides along in the ranks, and gives an officer a military [salute] with as much style as the First corporal in a crack company.”

Thomas C. MacMillan, writing for the rival Chicago Inter-Ocean, noted her “reputation of being a better horse-back rider, mule and bull-whacker and a more unctuous coiner of English, and not the Queen’s pure either, than any man in the command.” McGillycuddy himself said she was “the only woman in the party, dressed in soldier’s clothes, rode a horse astraddle, could drink and swear ‘like a trooper.’” He later added she was “something like Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she was not exactly ‘raised she growed.’”

The Road to Deadwood

— Courtesy South Dakota Tourism —

The Black Hills Expedition followed the route that would become famous, and well-traveled, as the Cheyenne-Deadwood Stage Road. Our route on U.S. 85 follows that trail. Take time for a stop at the Stagecoach Museum in Lusk, and to view one of the buildings related to the site of the Hat Creek Stage Station along the old stage road just east of Highway 85 north of Lusk. Tom Swan and John Storrie built the log building at the site in 1880.

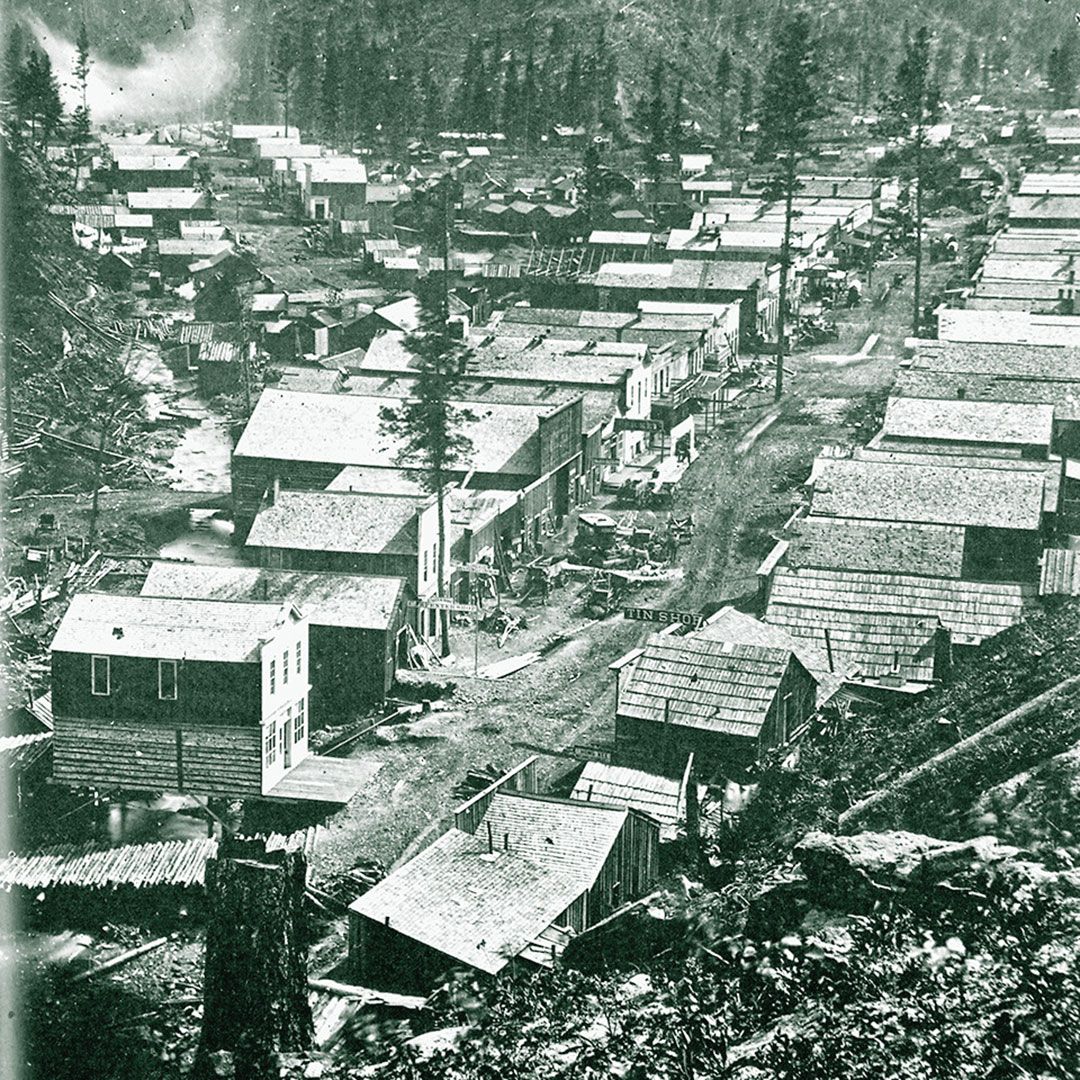

Visit the Newcastle Museum in Newcastle, and then continue on U.S. 85 to Cheyenne Crossing, South Dakota, where the highway turns east and becomes U.S. 14A, cutting through the western edge of the Black Hills to Lead and then to Deadwood, which became one of Calamity’s home bases, and is where she is buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery, next to James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok.

Deadwood became the heart of action in the Black Hills during Calamity’s time there. Wild Bill was gunned down there, and it’s known for a diverse cast of Old West characters—some of whom are brought back to life in the new movie version of Deadwood. There are plenty of places to explore, including the cemetery, the Days of ’76 Museum, Adams Museum and Historic Adams House. Of course, like Calamity Jane found, you also will be able to play some poker, or find a shot of whiskey and a good meal.

— True West Archives —

You probably won’t hear the language used in the HBO series and movie Deadwood (just like Calamity may not have heard—or used—some of that language), but you may hear some good tales about the characters of the place—from Calamity and Wild Bill to Seth Bullock and so many more. Calamity left Deadwood, and headed to Montana, where she had spent part of her childhood. She was in Miles City on February 11, 1882, then moved to Billings as the Northern Pacific Railroad also laid tracks toward the West. At times she was in Livingston, Lewistown and Missoula, but Montana did not claim her for long. By the latter half of the 1880s she was farther south, living and, according to some accounts, working as a prostitute in towns along the Union Pacific Railroad route in southern Wyoming.

Sorting out details of Calamity Jane’s life is a task for folks who like twists and turns in a story, as she certainly didn’t light long in any one place. She returned to the Black Hills, where she died in Terry, South Dakota, on August 1, 1903.

As you explore the Black Hills area (Deadwood, Lead, Custer, Hill City), keep an eye out for Calamity Peak, named by McGillycuddy for the intrepid female, who is both real—and legend.

Candy Moulton is the author of Valentine T. McGillycuddy: Indian Agent, Army Surgeon.