— Courtesy New Mexico Tourism —

Fort Sumner, New Mexico, has never been an easy place to live. Winters can be brutal. Summers are often blistering. The scenery’s spartan. Few describe the wind as meek.

For the Diné—or Navajo people—their confinement at Fort Sumner’s Bosque Redondo Reservation between 1863 and 1868 proved devastating. General James Carleton had dispatched Kit Carson to bring in the Indians, and Carson’s “scorched earth” policy, carried out during the winter of 1863-64, forced the Diné to surrender. Between the summer of 1863 and the winter of 1866, an estimated 11,500 Diné men, women and children were marched 400 miles. Ill-equipped for the journey, only 8,500 reached Bosque Redondo. “The Long Walk,” like the Cherokees’ “Trail of Tears,” remains a blight on our history.

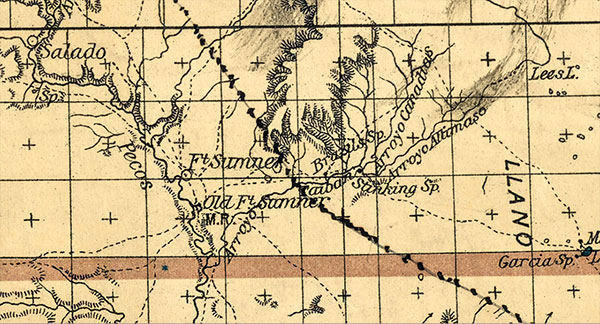

— New Mexico Map Courtesy NYPL Digital Collection —

At the reservation, which the Diné shared with roughly 400 Mescalero Apaches, all suffered. Firewood was practically non-existent, and the climate was drastically different than their homeland. Good water was hard to come by, and the Army at Fort Sumner had expected maybe 5,000—not closer to 9,000—prisoners here. Carleton envisioned a utopia where he would turn the Indians into farmers, but the irrigation system for the fields rarely worked, and “army worms” destroyed what few corn crops managed to grow. The Diné weakened. The Mescaleros got sick of the whole affair and escaped in late 1865.

“They told us this was a good place when we came,” Diné clan leader Barboncito said, “but it is not.”

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

It’s little wonder that the Diné considered Bosque Redondo a concentration camp or that after the Bosque Redondo Memorial opened in 2005, one of its first exhibits was “Anne Frank: A History for Today.”

Today, Billy the Kid might remain the main draw to Fort Sumner—with his grave and two museums—but the Bosque Redondo Memorial is the most historical and moving.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Yes, that memorial can be demoralizing, but there’s also a story of hope. The Diné left Bosque Redondo and returned to a portion of their homeland in 1868.

On June 13, 1868, the Santa Fe Weekly Gazette announced:

“In pursuance to the Stipulations made by Gen. Willian T. Sherman with the Navajos during his recent visit to the Bosque Redondo, the Navajos will begin to move from the latter reservation to one in their own country, between the 12th and 15th inst.

“The movement, which will be under the charge of Maj. Whiting, will be en masse and will be a grand display of native Americans, dressed in aboriginal costume and traveling in aboriginal style.”

The Senate ratified the treaty on July 25. President Andrew Johnson signed it on August 12.

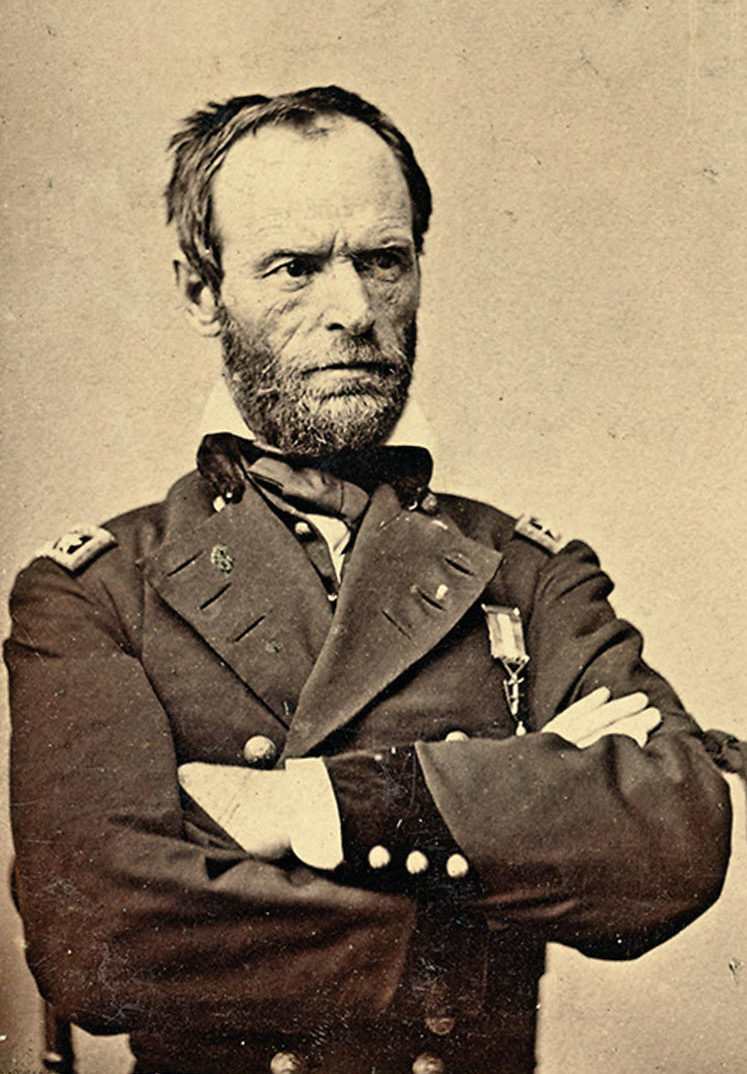

Earlier that year, Gen. William T. Sherman and the Grant Peace Commission had met with the Indians at the reservation. “I found the Bosque a mere spot of grass in the midst of a wild desert, and that the Navajos had sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair,” Sherman recalled.

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

During these negotiations, Barboncito said: “I hope to God that you will not ask us to go to any country but our own. When the Navajos were first created, four mountains and four rivers were pointed out to us, inside of which we should live, and that was to be Dinetah. Changing Woman gave us this land. Our God created it specifically for us.”

On June 1, Diné and white representatives agreed upon the terms. The treaty didn’t give the Indians all of their land back—the four sacred mountains did not fall within the reservation—but, unlike many Indian tribes, the Diné were returning to their own country.

The Army escorted the Indians and protected them on a long walk that did not seem quite as long. They began their return home on June 18.

— Courtesy Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress —

In his monumental Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West, Hampton Sides writes that some Diné “were so restless to get started that the night before they were to leave, they hiked ten miles in the direction of home, and then circled back to camp—they were so giddy with excitement they couldn’t help themselves.”

During the Long Walk, the Indians had been marched over different trails—one took them as far north as Fort Union in northern New Mexico. But they took one trail on their joyful journey home.

Basically following the Pecos River, they started north to near what’s now Santa Rosa (Route 66 Auto Museum, Mesalands Dinosaur Museum). They didn’t go to Las Vegas—perhaps because they had raided the town in August 1846—but the historic city (City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Rider Memorial Collection) is a good resting point for today’s travelers.

Leaving the Pecos River at Pecos (Pecos National Historical Park), the Indians bypassed Santa Fe for Galisteo and moved south toward Tijeras (Route 66’s “Musical Road,” on which your tires will play “America the Beautiful” as long as you’re driving 45 mph).

— Courtesy Steven Baltakatei Sandoval, Creative Commons —

Then they traveled west, along what today is Interstate 40, through Albuquerque (Albuquerque Museum, Petroglyph National Monument) and Laguna Pueblo (Laguna Burger is a carnivore’s mecca). When the Indians saw Blue Bead Mountain (a.k.a. Mount Taylor) north of Cubero in the San Mateo Mountains, they dropped to their knees and cried.

“We wondered if it was our mountain,” Manuelito said, “and we felt like talking to the ground, we loved it so.”

Continuing west, they moved through Grants (El Malpais and El Morro national monuments are worthwhile deviations) and reached Gallup (Richardson Trading Post, founded in 1913).

From Gallup, continue the journey to the capital of the Navajo Nation, Window Rock, Arizona, and check out the Navajo Nation Museum for the Diné side of the story.

The Diné had sung songs during much of the journey home. They still perform The Enemy Way ceremony for soldiers returning home who have been in combat and/or were wounded or captured. The ceremony brings the honorees into a state of balance—“Hozho”—in the universe.

In beauty I walk.

With beauty before me, I walk.

With beauty behind me, I walk.

With beauty below me, I walk.

With beauty above me, I walk.

With beauty all around me, I walk.

It is finished in beauty,

It is finished in beauty,

It is finished in beauty,

It is finished in beauty.

Johnny D. Boggs recommends Diné: A History of the Navajos by Peter Iverson and Four Masterworks of American Indian Literature by editor John Bierhorst.