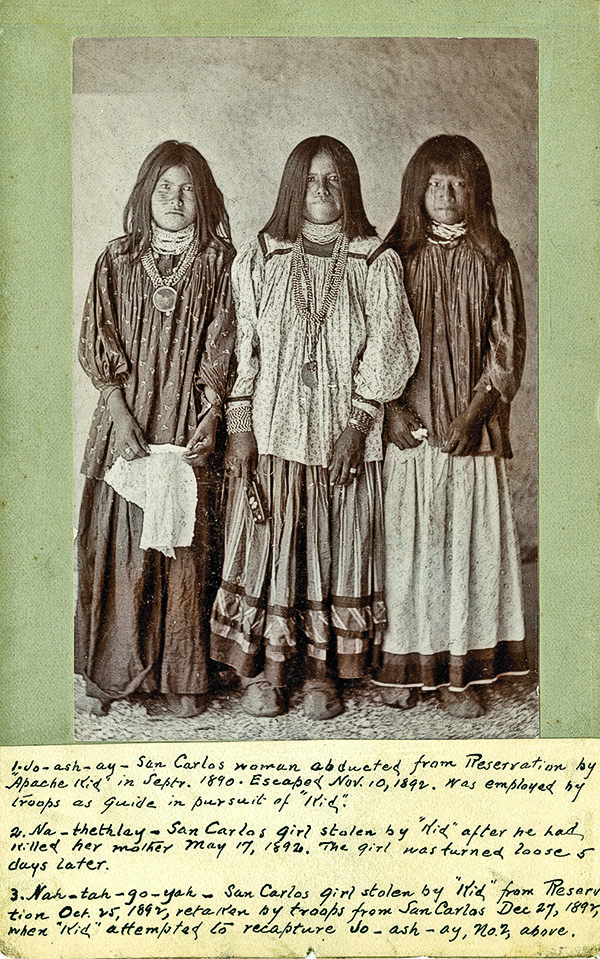

—All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted —

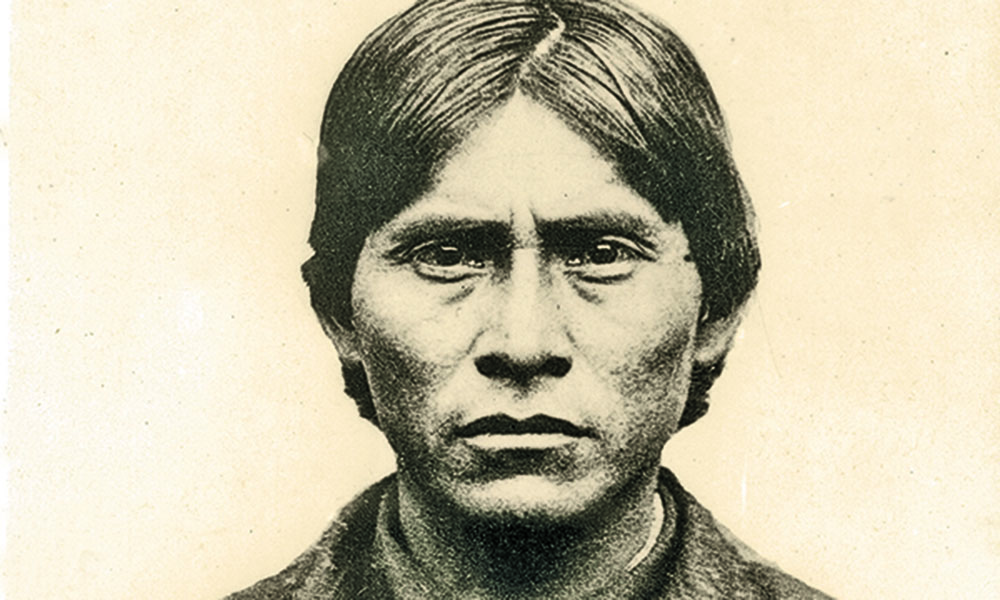

Everyone in the posse took notice of a pair of binoculars taken from the Apache’s body. The Apache Kid always carried them from the time he was a scout, and no other Sierra Madre Apache had been found with them. Only a few leaders, including Geronimo, had access to field glasses. The year was not 1886, however, and the surrender was long past. It was November 11, 1900, and yet another encounter with renegade Apaches, by Mormon settlers, had played out with bad luck for those who rode with El Chivito’s band.

The Apache Kid Identified

The New York Times reported the Apache Kid’s demise on November 23: “President Joseph F. Smith of the Mormon Church, who has arrived here accompanied by A.O. Woodruff and other church elders after a tour among the colonies in Mexico, reports the killing of the notorious Apache Kid in the recent Indian raid in Colonia Pacheco.” Posse members agreed that the fallen leader was the Apache Kid.

The Cluff brothers, Mormon President Anthony Ivins and church elder Orson Pratt Brown had either seen the Apache Kid at San Carlos or had viewed wanted posters of him. President Ivins had plans to claim the reward. Brown captured the scene on film, writing, “I had taken my camera with me, and I took a photograph of the Indian Chief. He had been shot through the nipple and the bullet came out on his back left side….” Yet no bounty was ever collected. No photos were ever found. Without proof, the death of the Apache Kid appeared to be an impossible dream, despite the posse’s visits to the San Carlos Apache reservation in Arizona Territory to claim their reward.

Nevertheless, the men believed they had gotten their man—the Apache who murdered members of the Thompson family in 1892 and rode roughshod for years over settlers in the rugged Sierra Madre Mountains and along the restless U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

Unintended Consequences

Journals and letters compiled by the men who participated in what they considered the final death throes of one of the Southwest’s most destructive and hated outlaws were amazingly detailed.

“…we have made preparations to go in the morning to dispose of the dead and see if we can find any more [Apaches] alive…” wrote Woodruff, in November 1900. Based on a comparison of participants’ accounts, here is how the event unfolded: The Apache Kid was often seen haunting rugged mountain trails along both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border after his 1889 escape from a wagon loaded with other Apaches on their way to Yuma prison in Arizona Territory. He reportedly had been killed at least 18 times over many years. Despite being accused of heinous crimes, the Apache Kid had the audacity to visit his family from time to time at the San Carlos reservation. After 1900, though, sightings of the Apache Kid were basically nonexistent. Yet not even the Apache Kid was gifted with the nine lives of a cat. He was flesh and blood. He cared about his family. He was incredibly brave and fiendishly clever. And he outsmarted just about everyone until that cold November day in 1900.

Despite the supposed end of the Apache Wars in 1886, times were hard in Colonia Pacheco, as in all the Mormon colonies of Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico. Although known as a “loner,” the Apache Kid learned he could work with other Apaches to steal more supplies to meet the band’s needs.

While Mormon settlers were out in the fields or attending church meetings on November 11, the Apaches struck quickly, stealing hundreds of pounds of potatoes and corn, livestock, blankets and other household items.

Winter was coming soon, and that food belonged to Mormon families. Enough was enough.

Ranchers Martin Harris and Thomas Allen were at first unsure of the bandits’ identities. The thieves might have also been dangerous renegade Mexicans from Dos Cabezas mines, who, like the Apaches, also raided Mormon colonies and isolated ranches. They would follow the thieves and then make their report to church elders. Anger simmering, the two men threw caution to the wind and rode after the bandits, running into a buzz-saw of unintended consequences.

They spotted the Apaches breaking camp. At least nine were well-armed, led by a warrior dressed in buckskin, a feathered war cap adorned with silver beads and trophies around his wrist and neck.

The leader, carrying field glasses and a rifle, motioned for the others to head out. Harris and Allen barely had time to hide behind some rock outcroppings before the Apaches unexpectedly headed toward them. A woman in the lead shouted in alarm and tried to turn her horse around. Except for the warrior leader, the band scattered, as was Apache custom. The leader, carrying a child strapped to his back, responded to the woman’s cry by grabbing for his rifle from the scabbard. It would not release. In desperation, he pulled again. Harris and Allen fired off enough shots to kill the woman and then turned their attention to the man who was furiously trying to detach the rifle. Too late…bullets hit him twice, and he fell from his horse. One of the bullets also killed the girl on his back. Harris later admitted how bothered he was that they had killed an innocent child. The stunned and lucky ranchers rode back to Pacheco and reported the altercation. The frontier-tough Mormon elders sent runners to other communities to warn them of raiders. Then both men took a posse to where the killings had taken place.

— Ranch photo By Bernd Brand/Harris’ Courtesy William S. Bryan —

Was the Dead Man the Apache Kid?

“It happened to my lot to come onto the first two Indians lying together dead,” Woodruff recorded in his journal. “I passed over them without saying anything and next found a full quiver with 60 well-made arrows in it and a fine bow also….

“After the ground for some distance around had been searched to be sure there were no live Apaches in the bush we took off the belts, pistols, moqisons [sic] and the Chiefs Cap, then found a good, deep crevice in the rocks….

“These Indians were all well clad in native attire, the…chief wore a belt filled with .45-70 shells, the squaw carried a knife, pistol and many trinkets. The little one had a knife in the belt. They were the most savage looking group I have ever seen.

“We followed the trail of those who escaped but did not find them nor their tracks. We returned to the Harris Ranch, had a dance and spent the night.”

Another description by Anthony Ivins revealed a man who took great pride in his appearance, even as he was living a dangerous hit-and-run existence: “The man wore a skull cap made from heavy buckskin, with a strip under the chin, on each side of which were small horn like projections to which tufts of eagle feathers were attached. A silver crescent…with a piece of polished turquoise in the center, adorned the front, while at the sides and behind, were ornaments of polished stone and silver.

“Around his neck, attached to a string of beads were a small Catholic cross and a Free Mason’s cross. The latter had contained an inscription but the letters had been obliterated.

“He wore a tight fitting, shirt, underneath which strapped to his body was a pair of French field-glasses. Belt, knife case, pouches and moccasins and other accouterments were all Indian made and showed excellent workmanship……”

Buried Twice

This macabre incident also included the posse burying the three Apaches twice, not to please the Mormon Elders, but to appease Mexican officials who wanted to make sure that no Mexicans had been killed by these gringos who lived among them. On November 22, the headlines declared, “Killed in Fight with Mormons. Apache Kid Meets His Death. A.O. Woodruff Present at His Burial.”

The posse placed a blanket in a crevice, Woodruff recounted, and laid the body of the leader first. They placed the girl at his feet and the female over both of them. They then respectfully added a blanket over the three bodies and then piled rocks, 3 feet high, on top.

The posse then checked the countryside for additional sign of Apaches or supplies. They located one stolen horse and saddle. The remainder of the band had escaped into the depths of the Sierra Madre Mountains. Mexican officials from Casas Grandes met with the Mormons at the burial site. The Mexicans removed the rocks and the blankets, divulging that the reports were true. “Sí, son indios bábaros,” one Mexican official said. (“Yes, they are savage Indians.”) After the grisly review, more individuals from the colonias examined the bodies. They agreed that the one appearing to be the leader was the elusive Apache Kid. Several of the men had freighted to and from San Carlos and had seen the young man while he was a scout at San Carlos. Others had observed his picture on the many wanted posters.

President Ivins also identified the slain warrior as being the Apache Kid, and Woodruff noted in his diary that the two planned to report the affair to Capt. Nicholson at San Carlos.

The posse reburied the bodies. President Ivins later wrote about the killing of the Apache Kid: “He killed Mormons and by Mormons was killed.” The Apaches undoubtedly viewed their dead leader as a brave combatant, fighting for the survival of his band in the only way he knew how.

Was the dead man the Apache Kid? The residents of the Sierra Madre Mountains who dealt with Apache raids for years believed so.

The Inventory

The list of items the posse took from the Apaches is not the story of rag-tag Apache remnants known to haunt the Sierra Madre cordillera between Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico. These broncos wore beautifully tanned buckskin, rode stolen horses and were well-armed. But fate had turned against them that winter.

The inventory items received by Mexican officials in Casas Grandes read like a mini-exhibit of Sierra Madre Apache artifacts. Whatever happened to them, no one knows. Officials perhaps kept them as souvenirs. An inventory item that jumps out at researchers are the “French” binoculars carried by the dead leader believed to be the Apache Kid. The Apache Kid was photographed with his famed field glasses.

“…at some point in his scouting career Kid began carrying binoculars on a long shoulder strap,” noted Phyllis de la Garza, in her biography of the Apache Kid. Here is the inventory list:

• Binoculars

• Bow, quiver and 40-60

• Moccasins-well made

• Three knives

• Cartridge Belts with .45-70 ammo

• Rifle

• Colt Revolver with pearl handle

• Bracelets

• Medicine belt taken from the dead woman, with roots and herbs attached

• Saddle (found later on a missing horse the Apaches left behind)

• Various trinkets; string of silver beads and feathered war cap with silver crescent and turquoise stone in the middle

• Knife cases and leather pouches of excellent craftsmanship

• Two crosses (Catholic and Masonic)

Lynda A. Sánchez wishes to thank genealogist William S. Bryan for his special assistance. Sánchez will publish a more detailed discussion of these never-before-published accounts in her manuscript on the Lost Apaches.