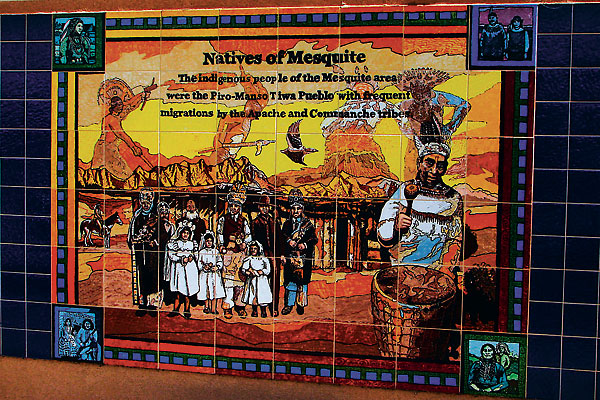

Few people have ever heard of the Piro-Manso-Tiwa tribe that is scattered around Las Cruces, New Mexico.

In fact, the tribe isn’t even a “recognized” American Indian tribe, an oversight the members have been struggling to correct with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) for the last 40 years.

In those four decades, they’ve filed mountains of documentation. Yet the tribe is closer to official recognition these days than it has ever been because of the help of a 31-year-old anthropology student who lived with the tribe and organized their archives to satisfy BIA demands. In the process, she has seen her own life changed by this small tribe.

Lee Ann Allen grew up in Baird, Texas, in a working-class family. She never even met an American Indian until 2008, when she was accepted into the Robert E. McNair research program at the University of North Texas. Lee Ann is the first person in her family to attend college—re-entering after an eight-year break.

Thanks to guidance from her mentor, retired anthropology professor Diane Ballinger, Allen decided to help the tribe organize its archives. She had to solve a problem first. “…no non-Indian or non-tribal member has ever had access to their archives,” she says.

In the spring of 2008, she met with the tribal members. “We sat around the dining room table at the cacique’s house, and they wanted to be sure of me,” she says. “It didn’t take long before they said, ‘You could help us in the archives.’”

She remembers being thrilled at their acceptance of her. She also remembers the daunting feeling she had when she saw the 20 years worth of unorganized material she needed to categorize.

For the last two summers, she’s lived at the home of Edward Roybal Sr.—the spiritual leader or cacique of the tribe—and his wife, and worked six to nine hours a day, sometimes six days a week.

She says the need for recognition as an official tribe is obvious. “Without it, they’re invisible,” she says. “Without recognition, they don’t feel respected. That’s one reason this program has become very important to me. It’s amazing to see how tenacious they’ve been.”

In April of 2004, the cacique’s son and Tribal Gov. Edward Roybal II reminded the Senate Indian Affairs Committee of the pending request for recognition. Ever since 1888, when U.S. Land Commissioner Eugene Van Patten helped the tribe obtain a 120-acre land grant to establish the Town of Guadalupe, the federal government’s recognition of the tribe has been evident, he testified. From 1890 to 1910, some 110 children from the pueblo were sent to Indian boarding schools. To this day, Roybal II stressed, the Piro-Manso-Tiwa tribe has been tacitly recognized by the Indian Health Service, the Bureau

of Land Management and the governments of New Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada.

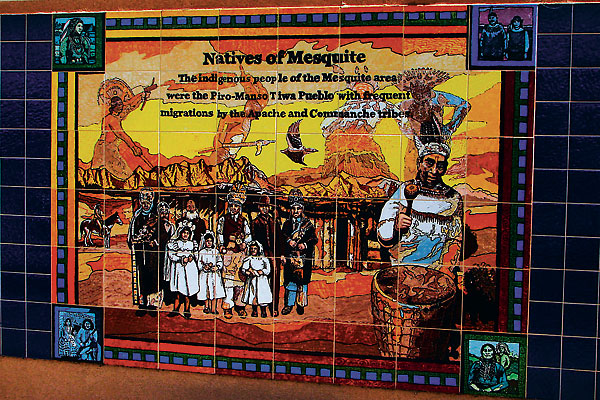

The tribe’s ancestors were the first Pueblo people Spanish explorer Oñate met in 1598 in what is now the Las Cruces area. Fray Garcia de San Francisco later settled some of them at the North Pass (El Paso del Norte)—modern-day Ciudad Juarez in Mexico—where he established the Our Lady of Guadalupe Mission in 1659. After the 1680 Pueblo Revolt against the Spaniards and the 1780-82 smallpox epidemic, the Manso, Piro and Tiwa merged into the Pueblo Indians of Guadalupe under one cacique. The 1844 census notes Guadalupe Indians resettling Mesilla Valley, with the Avalos and Jemente families among the first settlers of Las Cruces.

This long-storied tribe has never shared its religious practices with outsiders, and yet it did so, to comply with the BIA’s documentation request. “It’s very intrusive,” Allen says of the process. “It amounts to a group of Indians having to prove to a group of non-Indians that they’re Indians.”

Although some larger tribes seeking recognition have been able to hire professionals to put together their petitions, the Piro-Manso-Tiwa tribe is not one of them. “A poor tribe must rely on a grassroots process,” Allen says.

Allen’s work with the tribe has already been recognized: in 2009, she won the top award from the Society for Applied Anthropology. Her experience has also encouraged her to pursue a career in applied anthropology. “I want to work for human rights and work to improve the lives of others. This gave me the experience to do field work to cultivate a relationship with people who were complete strangers and have become extremely dear to me.”

Allen graduated in May and hopes to continue working with the tribe as a graduate student. She seems confident that the long-awaited tribal recognition will either come this year or early in 2011, and she wants to be around for the celebration.