When Yellow Wolf (He-Mene Mox Mox) sat down with Lucullus McWorter to relate his tale of the 1877 Nez Perce War, some questioned his motives, but Yellow Wolf himself said, “I am telling my story that all may know the war we did not want.” His account, one of few from the Nez Perce who took part in that epic flight across the West, has been used by every writer who has since chronicled the hegira.

A member of the band that followed Chief Joseph, Yellow Wolf was a top warrior when the tribe found itself in flight and under attack by troops commanded by Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Yellow Wolf’s grandfather and Old Chief Joseph’s mother were sister and brother, making him a first cousin to Chief Joseph, but in his account, Yellow Wolf uses the term “uncle” to refer to Chief Joseph, the peace chief who became a symbol for the Nez Perce during that fateful year. Their blood ties meant that quite often Yellow Wolf shared a lodge with Chief Joseph and his family.

Born in the Wallowa Valley of northeast Oregon, Yellow Wolf traveled eastward as a young man with other warriors, hunting bison and other game in the area in and around Yellowstone National Park. “We had a good country until the white people came and crowded us,” he said.

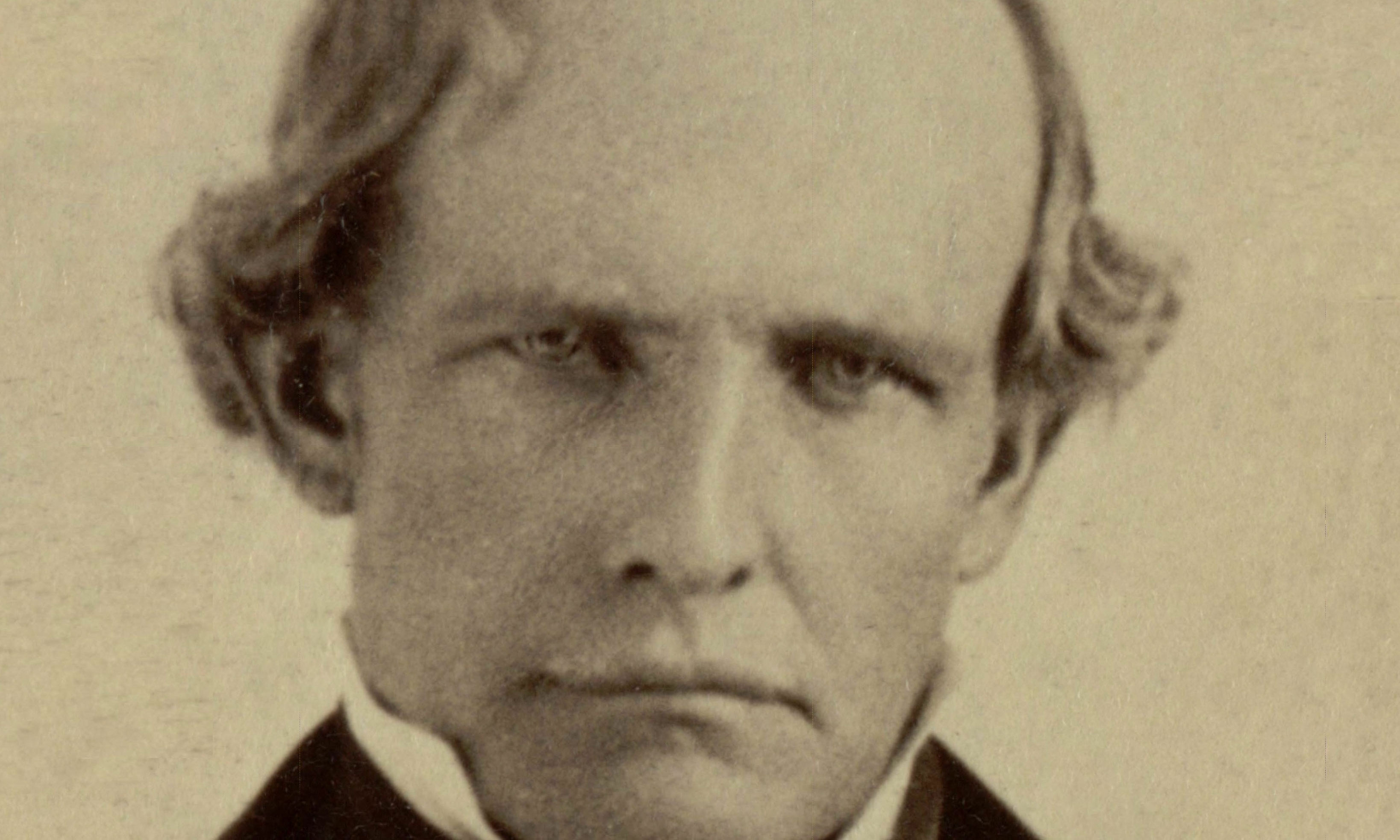

In 1863, the Nez Perce people gathered in council with representatives of the United States government to try to work out an agreement that would halt the march of white settlers and miners onto their lands. The council document, which became known as the Thief Treaty, led to the permanent fracturing of Nez Perce power.

– All Photos Courtesy NPS.gov Unless Otherwise Noted. –

By 1877 Chief Joseph had become the chief of the Wallowa band, but there were other important leaders who took part in a council ordered by General Howard. They included Ollokot, Chief Joseph’s brother, the recognized war chief of their band, plus White Bird, Toohoohoolzote and Looking Glass. Yellow Wolf later said, “To all of us General Howard now spoke: ‘If you do not mind me, I will take my soldiers and drive you on the reservation.’”

The Nez Perce tribes, who had not signed the 1863 treaty, resisted. But, with more pressure on them in late May 1877, they left their home valleys and took their families into Idaho. They were gathered in an area south of the planned reservation lands at Lapwai, trying to maintain their freedom and establish a way to avoid following the dictates of the agent, when some young men took matters into their own hands. One of them had suffered greatly when his father was killed by white men, and he and several companions retaliated by killing some white settlers.

This was the tipping point as the military now set out to force the Nez Perce people onto the reservation. The opening attack by military troops on Nez Perce families took place at White Bird Canyon on June 17, 1877.

Yellow Wolf told McWhorter: “We were not expecting war with the whites.” In the White Bird Canyon fight, Yellow Wolf said he “ran to strike one soldier with my bow. I leaped and struck him as he put a cartridge to his gun. I grabbed the gun and shoved hard. The soldier went over backward, but he was not hurt. I wrenched the gun from him, and at some time a warrior back of me killed him.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

At the time, Looking Glass and the families who followed him were not with Chief Joseph and the larger group of Indians. They were in central Idaho, where a different group of soldiers found and attacked their camp, burning most of their supplies. This unprovoked onslaught led Looking Glass to join forces with the other bands, adding strength in numbers and setting up a powerful confederacy. With Looking Glass was Yellow Wolf’s mother, who had saved Yellow Wolf’s rifle from the attack on Looking Glass’s camp when she took it apart and put it in her pack to keep it from being seen. “I was glad to see my rifle,” Yellow Wolf recalled. “My parents had brought it for me with one good horse. I now had my own sixteen-shot rifle for the rest of the war.”

Still attempting to avoid direct fighting with the troops that massed against them, the Nez Perce people moved toward the Clearwater River. They were racing horses on July 11, when the troops once again attacked in a battle that lasted two days. Yellow Wolf said as the fighting began he “jumped on my horse and galloped down the hill.” He saw spurts of dust where bul-lets struck the earth near him so he “whipped my horse for all in him.” Though being shot at, Yellow Wolf said

he re-called the instruction of his uncle Old Yellow Wolf: “If you go to war and get shot, do not cry!”

The attack led to the destruction of Indian lodges and possessions. Those not destroyed were abandoned as the tribe fled east. They headed into the mountains, crossing Lolo Pass, on a route roughly parallel to U.S. Highway 12. They skirted around troops who had moved in from Montana and set up a barrier in the canyon, a place known as Fort Fizzle, and ultimately dropped into the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana. Now they believed that they had escaped the pursuing troops in Idaho, so they trailed south to the Big Hole Valley.

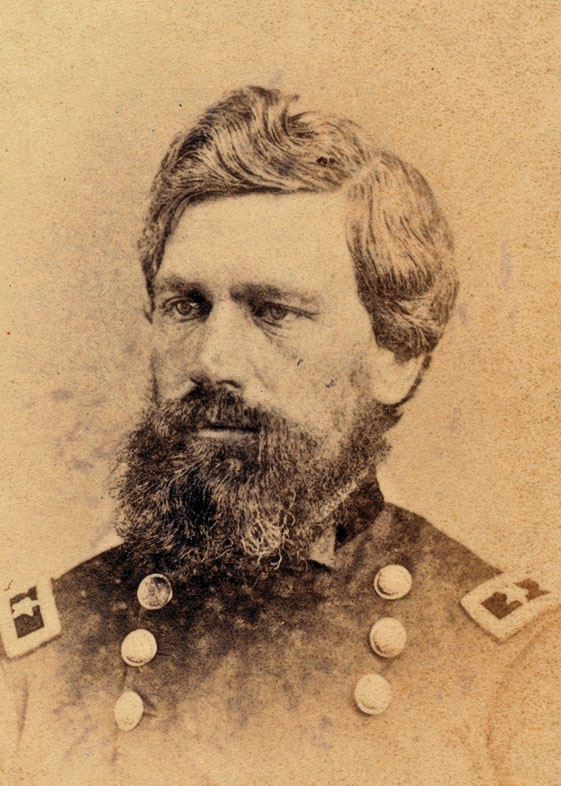

On the morning of August 9, 1877, Yellow Wolf was in a lodge at the lower end of the camp when soldiers under the command of Col. John Gibbon attacked. Yellow Wolf did not have his rifle with him, but when he heard the initial gunfire, he “grabbed my moccasins and with others ran out of the tepee. I had only my war club.” Once outside, a younger boy gave Yellow Wolf a gun, but it had only one shell. As he entered the fray, he came upon a wounded soldier who had a gun and belt full of cartridges. “I struck him with my war club and took his government rifle and ammunition belt…. I now had a gun and plenty of shells.”

The battle at the Big Hole was a tough blow to the Nez Perces, with many injured and killed. As the young men like Yellow Wolf fought and held the soldiers at bay, the families, under direction of Chief Joseph, fled south.

After the Big Hole and for the next weeks the people traveled across western Montana, swung south into Idaho, where some of the warriors raided an army camp, stealing what they thought were horses in a night raid at Camas Meadow, only to realize when the sun rose that they had run off with mules.

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

In late August the Nez Perces crossed into Yellowstone National Park, by following the Madison River, took a tourist party captive for a few days, and forced one of the men with the party to guide them through the park. The Nez Perce families reached the Yellowstone River, crossed through Pelican Valley and then followed the Lamar River out of the park to the Clarks Fork River. They passed near today’s Bridger, Montana, and turned north again. Then they headed across Montana, intending to join Sitting Bull and his followers, who had fled to Canada following the Lakota victory at Little Bighorn the previous year.

By late September they reached the Bear Paw area, only 40 miles from the Canadian border, and the present town of Chinook, Montana. They believed they had outrun General Howard and would soon be across the Medicine Line—the U.S.–Canadian boundary—and with Sitting Bull, where they could figure out their future.

But the Army had organized a new command led by Col. Nelson Miles that came in from the southeast and intercepted the Nez Perces at the Bear Paw. A five-day battle and siege led to the death of Nez Perce leaders Ollokot, Looking Glass and Toolhoolhoolzote. The soldiers captured Chief Joseph, but released him when Nez Perce tribesmen took soldiers as captives. As the weather turned colder and food supplies for the tribespeople dwindled, Chief Joseph made the decision to surrender his rifle in order to save the old people and the children. White Bird and many of his followers, including Chief Joseph’s own 12-year-old daughter, fled north and successfully reached Canada, but Joseph and those most loyal to him, including Yellow Wolf, surrendered.

– Courtesy Idaho Tourism. –

They were force-marched to Fort Keough on the Yellowstone River and then taken by boat to Fort Abraham Lincoln in Bismarck, North Dakota, before ultimately being sent downriver to Fort Leavenworth, Baxter Springs, Kansas, and Indian Territory. They called this new region Eeikish Pah (“the hot place”) and many of them died before they were ultimately allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest.

Yellow Wolf traveled by train with Chief Joseph and the other members of the

Chief Joseph Band to settle on the Colville Reservation in eastern Washington, where he would tell his story to Lucius McWhorter and where he died in 1935. He is buried in the small cemetery where Chief Joseph, who had died in 1904, is also buried. Their story is forever entwined.

Candy Moulton is the author of the Spur Award-winning biography Chief Joseph: Guardian of the People (Forge), which is excerpted on pages 22-29.