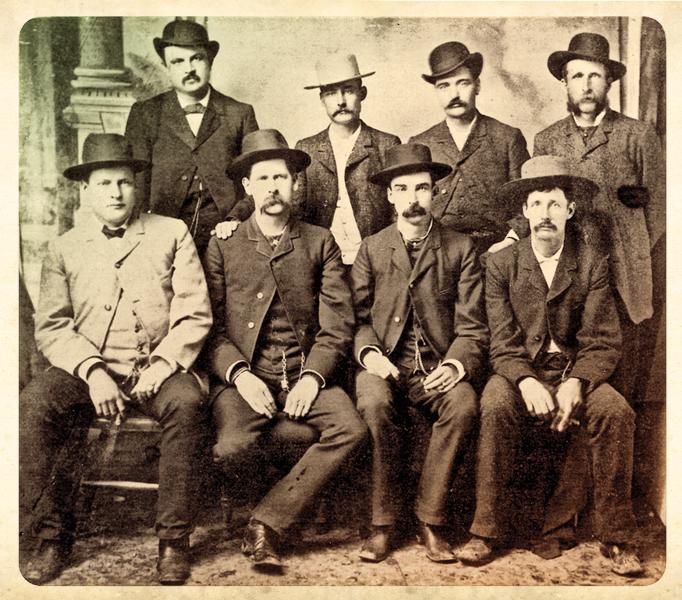

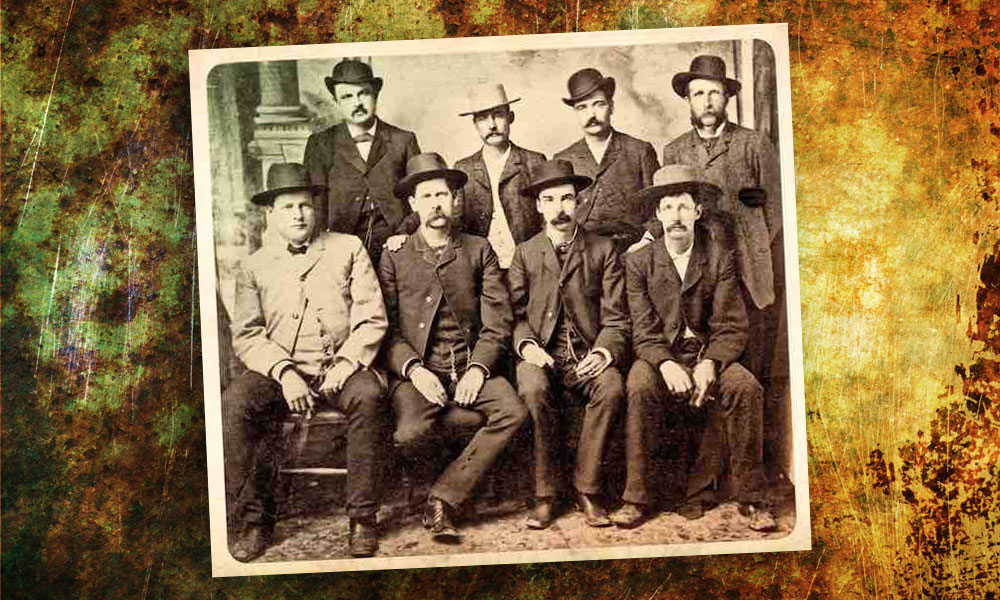

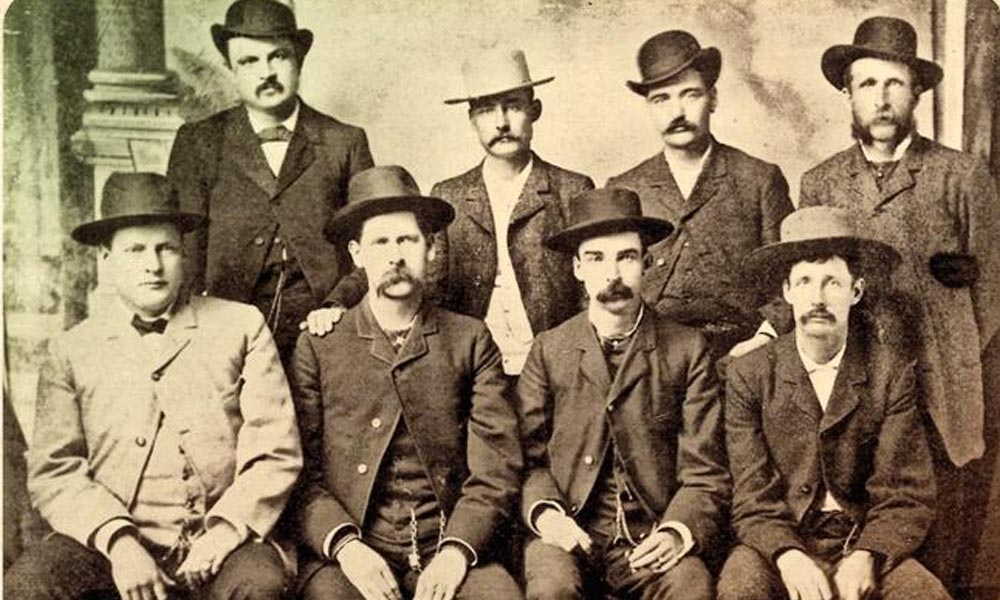

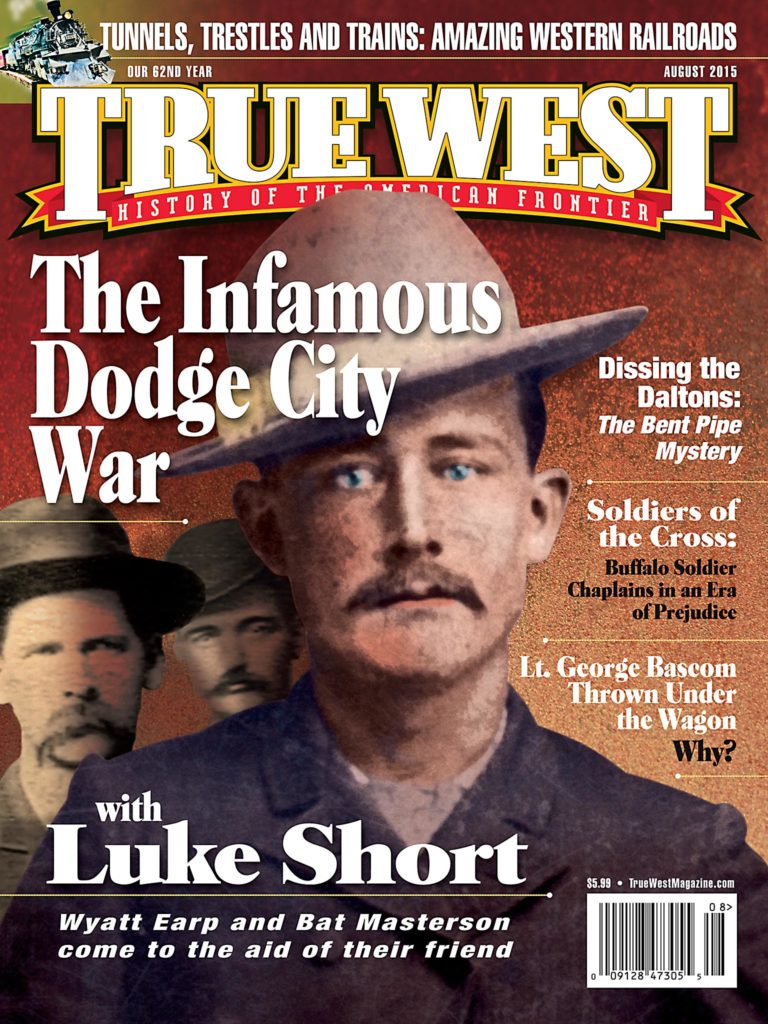

In the iconic photograph, a group of stone-faced men stare stolidly back at the camera, giving no indication that theirs was a celebratory pose, an image of the “Dodge City Peace Commission” taken to mark the victory of one group of gamblers and hard cases over another.

In the iconic photograph, a group of stone-faced men stare stolidly back at the camera, giving no indication that theirs was a celebratory pose, an image of the “Dodge City Peace Commission” taken to mark the victory of one group of gamblers and hard cases over another.

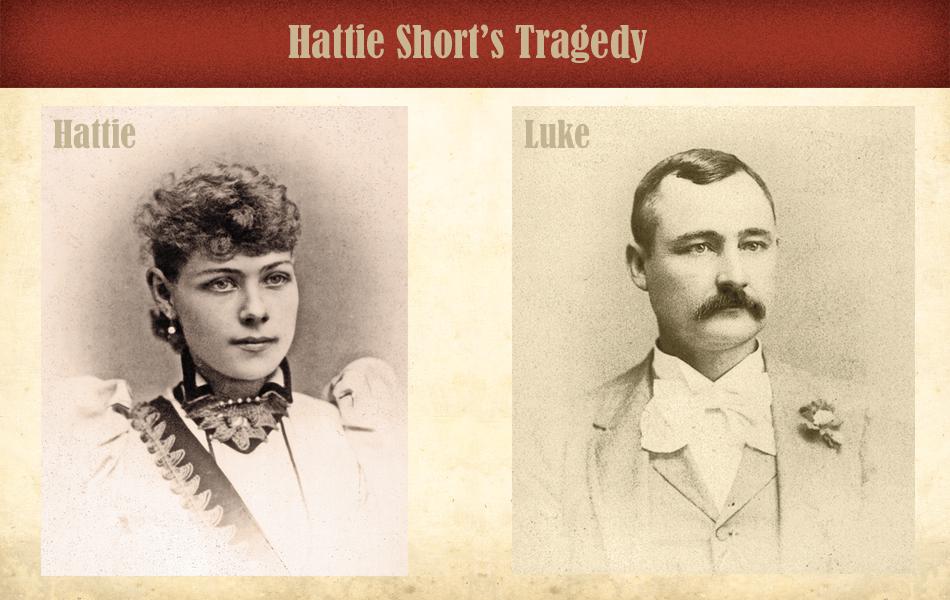

Standing in the rear, the men to either side of him standing much taller, is the diminutive Luke Short. It was for his sake that the so-called “Dodge City War” occurred in the first place, but for some reason, he never quite achieved the prominence of two other men in the group—Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. Short had been a cowboy, scouted during the Indian Wars and evolved into a well-known sporting man, but he has remained in the shadows of others, familiar only to aficionados of the Old West.

Trouble in Dodge City

Short first met Earp, William H. Harris and Masterson, in that order, in Tombstone, Arizona, after arriving there in November 1880. Harris was well acquainted with Earp from Earp’s time in Dodge City, Kansas. Based on their previous friendship, Harris, who ran the gambling concession at Tombstone’s Oriental Saloon, convinced the owners to engage Earp as a faro dealer. Short and Masterson worked for the Oriental as “lookouts” hired to protect the game. In fact, Short was a lookout at a faro game when he became involved in his first celebrated gunfight, on February 25, 1881 (see p. 40).

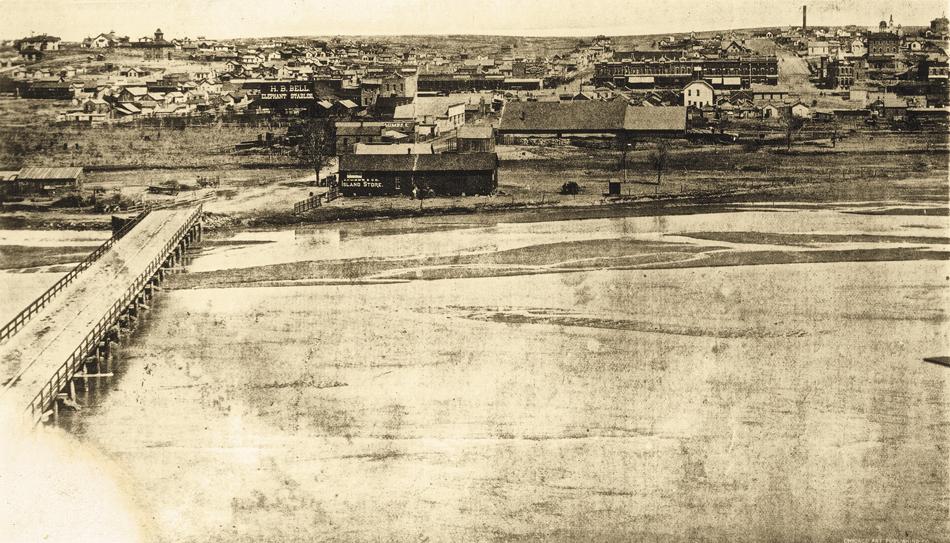

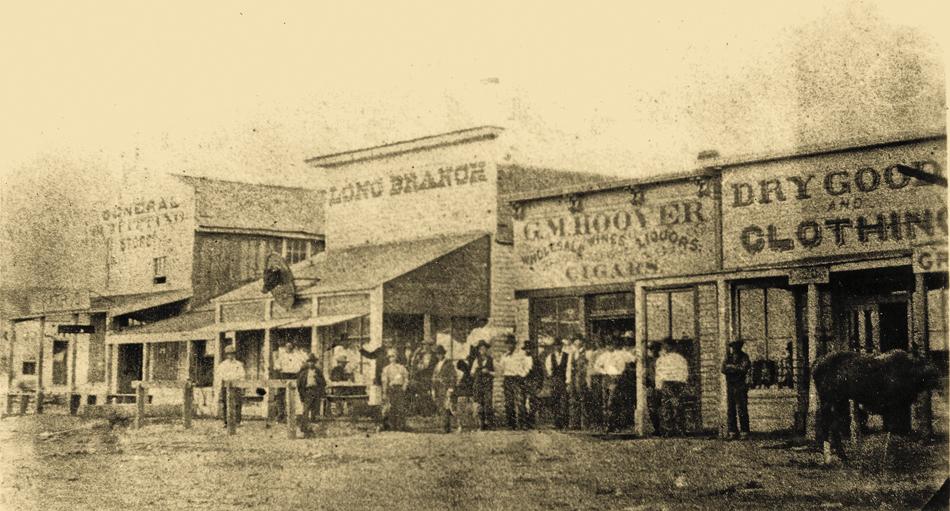

The first time Short stepped foot in Dodge City was when he moved to the Kansas burg in April 1881. By that time, Harris had sold out his interest in Tombstone and provided Short with employment as a faro dealer at the Long Branch Saloon in Dodge City that he owned with partner Chalk Beeson. On February 6, 1883, Beeson sold his share of the Long Branch to Short.

The month after Short and Harris formed their partnership, Harris entered the mayoral race against Lawrence E. Deger. He lost to Deger, by a vote of 143 to 214, on April 3. On April 28, officers arrested three women employed by Short at the Long Branch, in accordance with a new ordinance to suppress vice that Mayor Deger had authorized.

The Ford County Globe reported: “It was claimed by the proprietors that partiality was shown in arresting [the] women in their house when two were allowed to remain in A. B. Webster’s saloon, one at Heinz & Kramer’s, two at Nelson Cary’s, and a whole herd of them at Bond & Nixon’s dance hall.” If that was true, “it would be most natural for them to think so and give expression to their feelings.”

The “expression to their feelings” turned out to be a gunfight between Luke Short and policeman Louis C. Hartman, later that evening.

Short later told a newspaper that the law knew “their policeman attempted to assassinate me and I had him arrested for it and had plenty of evidence to have convicted him, but before it came to trial they had organized a vigilance committee and made me leave, so that I could not appear against him.”

Deger and associates forced Short, and four others arrested, to leave town. “…about one hundred and fifty citizens were on watch [May 7, 1883], and a large police force is still on duty night and day,” The Dodge City Times reported. Deger, the police force and the Dodge City citizens “are determined that the lawless element shall not thrive in this city.”

The Invitation

Short petitioned Gov. George Glick to intervene. Stressing he was “entirely innocent” of assault against Hartman, Short stated that after he had paid his $2,000 bond, he was arrested again, without stated charge. Then men led by Mayor Deger chased him out of jail and told him to leave and never return.

When Gov. Glick asked Sheriff George T. Hinkel to explain, the sheriff stated Mayor Deger had compelled “several persons to leave the city for refusing to comply with the ordinances.” The sheriff stressed that “[n]o such mob exists nor is there any reason to fear any violence as I am amply able to preserve the peace.”

The governor sent a blistering response to Hinkel: The action of the mayor in compelling citizens to leave town for not obeying the ordinances “simply shows that the mayor is unfit for his place, that he does not do his duty, and instead of occupying the position of peace maker, the man whose duty it is to see that the ordinances are enforced by legal process in the courts, starts out to head a mob to drive people away from their homes and their business.”

The governor understood the matter as “simply a difficulty between saloon men and dance houses.” He worked out an arrangement in which Short could return to Dodge City for 10 days “for the purpose of closing his business,” during which he would be “perfectly safe against molestation of any kind.”

In a letter written by 13 Dodge City citizens, published in the Topeka Daily Capital on May 18, the citizens added, that if Short overstayed the 10 days, they “would not be responsible for any personal safety.”

Short called the offer a “very liberal concession on their part,” but he had no desire to accept. He would rather trust himself in the hands of wild Apaches than trust to the protection of men such as Deger to “perfect the plans of my assassination.” He would return, he stated, when his enemies least expected him, and not “in answer to any invitation which they may extend to me.”

Gun-Toting Supporters

Twelve other citizens sent a letter to the governor requesting that Short be allowed to return to Dodge City and “defend himself in the court of the County.” On the same date as that letter—May 12—a newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri, published a report that must have alarmed the “law and order” faction in Dodge City. The Kansas City Journal stated that, on the previous day, “a new man arrived on the scene who is destined to play a part in a great tragedy.”

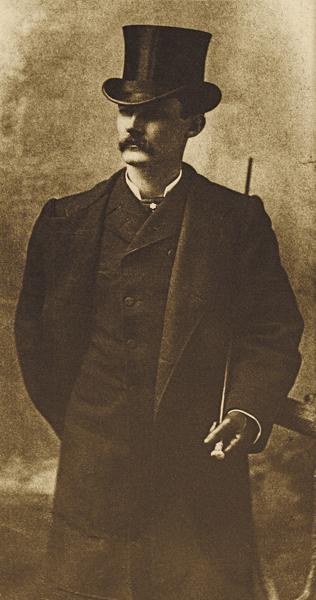

The “new man” was Masterson, ex-sheriff of Fort County, described by the paper as “one of the most dangerous men the West has ever produced.” Masterson was going to visit Dodge City, and within 24 hours, “a few other pleasant gentlemen [will be] on their way to the tea party at Dodge City.” Those named included Earp, “the famous marshal of Dodge,” Joe Lowe, “otherwise known as ‘Rowdy Joe,’” and the mysterious “Shotgun” [John] Collins, but “worse than all is another ex-citizen and officer of Dodge, the famous Doc Halliday [sic].”

On May 21, a train carrying Masterson stopped in Dodge City. That same day, Short arrived in Caldwell, Kansas, a cattle town nearly 200 miles southeast of Dodge City. The Caldwell Journal described Short as a “quiet unassuming man, with nothing about him to lead one to believe him the desperado the Dodge mob picture him to be.”

Ten days later, Earp returned to Dodge City. The former deputy city marshal arrived, “looking well and glad to get back to his old haunts, where he is well and favorably known.”

Earp was too well known as far as Sheriff Hinkel was concerned. Within hours of Earp’s arrival, Hinkel sent a telegram to Gov. Glick, asking if he could send Adjutant Gen. Thomas Moonlight to Dodge City “tomorrow” with the power to organize a company of militia. Hinkel knew if Earp and his cronies were assembling to do harm to any Dodge City citizen, the sheriff would be helpless to stop them.

Earp joined Short in Kinsley, and, on June 3, the two, with W.F. Petillon, rode the rails to Dodge City. “Shotgun” Collins and Masterson were meeting them there. Unless the city authorities backed down, Dodge City was about to get some “lively news.”

The Ford County Globe reported Short’s return in a manner suggesting the time had come to settle scores, alerting readers that “Luke Short…has come to stay.”

The day after his return, June 4, Short was in the Long Branch Saloon, well protected by several gun-toting supporters. Backed into a corner, Mayor Deger issued another proclamation, one that closed all the gambling places in town. Never considered as the most diplomatic of men, Masterson appeared to extend an olive branch, but with a sprinkling of sarcasm, in a letter to friends in Topeka. He wrote that upon his arrival in Dodge City, a “delegation of friends” met him to escort him “without molestation” to the Harris & Short establishment. Certainly with tongue in cheek, he continued: “I never met a more gracious lot of people in my life. They all seemed favorably disposed, and hailed the return of Short and his friends with exultant joy.”

Masterson proved to be a master at articulating his thoughts without resorting to the Colt revolver.

Short contributed to Masterson’s letter, hinting that the gambling houses would open soon. “The closing of the ‘legitimate’ calling has caused a general depression in business of every description, and I am under the impression that the more liberal and thinking class will prevail upon the mayor to rescind the proclamation in a day or two.”

Adjutant Gen. Moonlight agreed that the ordinance had been bad for business. He wrote to Sheriff Hinkel that the “cattle trade will soon begin to throng your streets, and all your citizens are interested in the coming. It is your harvest of business and affects every citizen, and I fear unless the spirit of fair play prevails it will work to your business injury.”

On June 7, the Evening Star of Kansas City, Missouri, reported on the “band of noted killers” in Dodge City. Along with Earp and Masterson were Holliday and Charlie Bassett. The paper described Bassett as a “man of undoubted nerve” who “has been tried and not found wanting when it comes to a personal encounter.” Holliday was too well known “to need comment or biography.” Notices had been posted up ordering these men classed as killers out of town, and “as they are fully armed and determined to stay, there may be hot work there to-night.”

Dodge City saw no “hot work” that night, but the conflict known as the “Dodge City War” did conclude that evening. Although a few minor points had to be worked out, Adj. Gen. Moonlight brought about a peaceful settlement between the two “warring factions.”

The gunfighters who came to Dodge City to support Short had represented a real threat, but their formidable presence did not bring together the opposing factions; simple economics did. Adjutant Gen. Moonlight felt satisfied with the results: No fatalities. Not even a wounded warrior on either side.

The officers admitted “that in running Short out they made a horrible mistake, which has cost the town thousands of dollars.”

No one could now claim ignorance that, in the pursuit of the almighty dollar, the question of the degree of vice—whether or not prostitutes frequented gambling halls—was no longer so important.

On June 9, the two factions had a final meeting. All those who had been chased out of town were back, with no fear of assassination or further trouble. At a new dance house just opened that Saturday night, the former enemies settled their differences, agreeing to stand by each other for the good of their trade.

History Captured on Film

The next day, Earp and Masterson were preparing to return to Colorado on a westbound train. Before leaving town, they got together with Short and five others for a group photograph. They posed inside a large tent, the temporary studio of Dodge City photographer Charles A. Conkling. One of the most reproduced photographs of Wild West gamblers and gunfighters, the historic group portrait is titled the “Dodge City Peace Commissioners.”

Nearly 50 days after the photo was taken, it was reproduced, as an engraving, in the July 21 issue of The National Police Gazette, which noted, “the ‘peace commissioners,’ as they have been termed, accomplished the object of their mission, and quiet once more reigns where war for several weeks and rumors of war were the all absorbing topic. All the members of the commission, whose portraits we publish in a group, are frontiersmen of tried capacity.”

Standing in the photo, from left, were Harris, Short, Masterson and Petillon. Seated, from left, were Bassett, Earp, Michael Francis “Frank” McLean and Cornelius “Neil” Brown. Prints were made of the photo and given to each of the eight “Peace Commissioners,” as well as others who had supported Short.

Editor Nicholas B. Klaine, of The Dodge City Times, took a swipe at Petillon, stating, “The distinguished bond extractor and champion pie eater, W.F. Petillon, appears in the Group.” The reference to Petillon being a “champion pie eater” does not point to him having won a contest at a country fair, but to his habit of scooping up slices of pie at various Dodge City saloons that had a “free lunch” counter.

Although the Dodge City War was now over, Gov. Glick kept his promise to commission the militia for the town, just in case. Appropriately named the “Glick Guards,” the company comprised supporters of both groups during the saloon war, including Harris, Petillon and Short.

A couple of months after life calmed down in Dodge City, Short was interviewed while in Kansas City, Missouri. Klaine reprinted a portion of the interview in the Dodge City Times. The reporter asked Short if he was running his business as he had been before the “agitation occurred.” Short replied, “Yes, sir; I am going ahead as usual. I returned to stay. Those men made a bad play and could not carry it out.”

Yet Short was rapidly losing interest in Dodge City. He was often out of town, heading to Texas to explore opportunities in Dallas, San Antonio and Fort Worth. He returned to Dodge City to settle up his affairs. Both he and Harris sold the Long Branch to new owners in November.

Klaine reported Short and Masterson’s departure on November 16 to Texas, in his signature style: “The authorities in Dallas and Ft. Worth are stirring up the gambling fraternity, and probably the ‘peace makers’ have gone there to ‘harmonize’ and adjust affairs. The gambling business is getting considerable ‘shaking up’ all over the country. The business of gambling is ‘shaking’ in Dodge. It is nearly ‘shook out’ entirely.

This edited excerpt is from The Notorious Luke Short: Sporting Man of the Wild West, by Jack DeMattos and Chuck Parsons and published this year by University of North Texas Press. DeMattos is the author of six books on Western gunfighters, including Mysterious Gunfighter: The Story of Dave Mather. Parsons is the author of Captain John R. Hughes and The Sutton-Taylor Feud, and coauthor of A Lawless Breed, a John Wesley Hardin biography.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy Boot Hill Museum, Dodge City, Kansas –

– Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka –