— Courtesy Library of Congress —

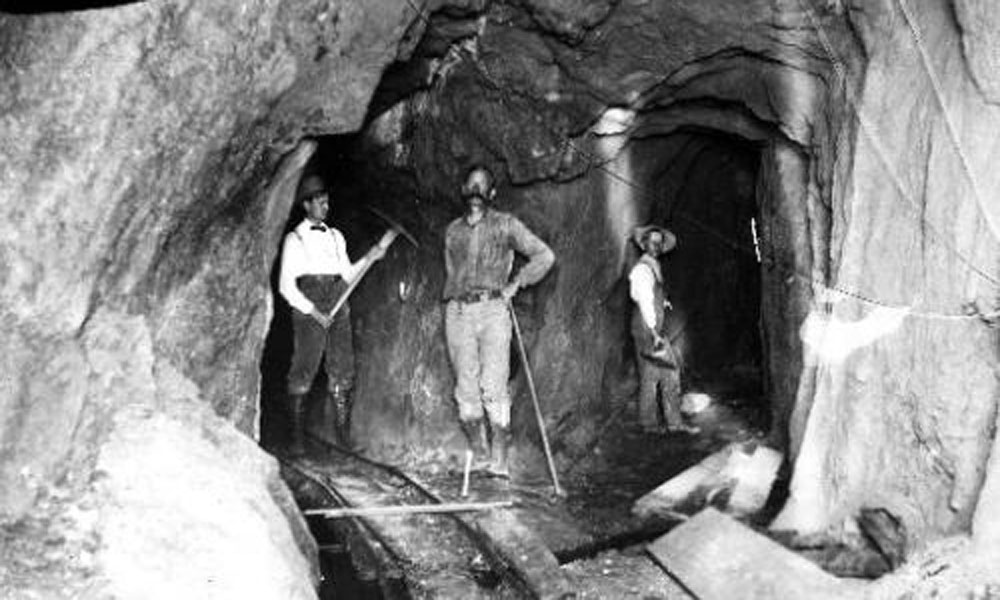

Mining was vital to the growth of the Old West—perhaps more so than even the cattle industry. It also led to violent class struggles between mine owners and workers, especially after the miners organized.

One of the most important incidents took place in the Coeur d’Alene Mountains of Idaho, where a strike was called in February 1892. Company guards shot and killed five strikers. The workers retaliated by shipping more than a hundred strikebreakers out of town. Federal troops were called in, arresting more than 600 strikers and held them—without charges—in a stockade. Miners across the West were outraged.

So the next year, in May of 1893, representatives of several Western miners’ groups met in Butte, Montana. After five days, they formed the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). From the start, the WFM was a radical organization that was willing to use violence.

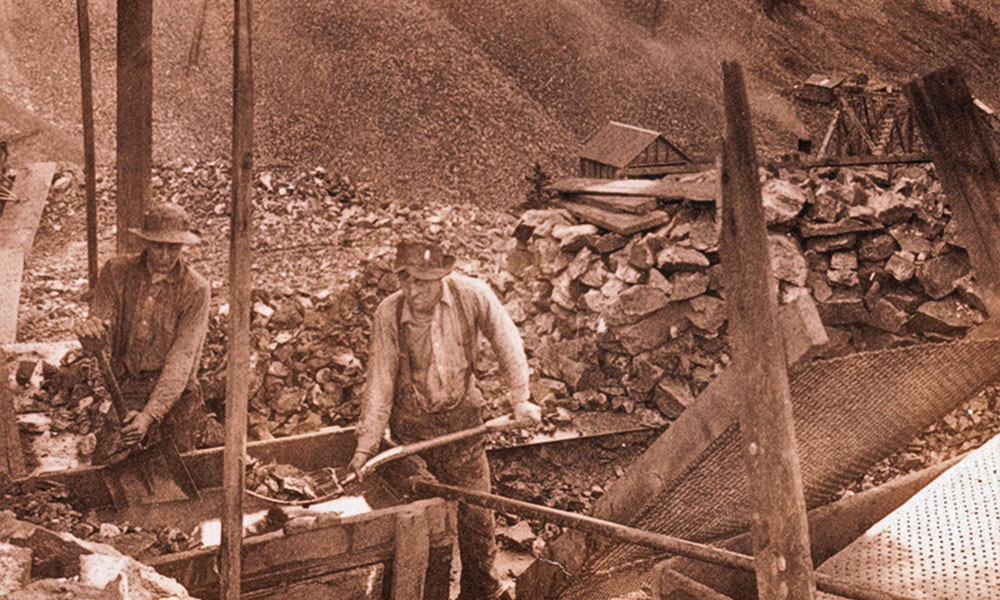

The WFM first took action during the Cripple Creek, Colorado, strike of 1894. Mine owners tried to increase the workday from eight hours to 10 hours. Union members walked out for five months—and dynamited some mines, buildings and equipment. Eventually, the owners gave in, kept the eight-hour workday and gave the miners a pay raise. The WFM boasted of the victory and quickly gained even more members.

The struggle moved on to Leadville, Colorado, in 1894-’95 as miners walked off the job, looking for increased pay. Again, violence broke out, the state militia took over and the strike came to an uneasy conclusion.

In 1899, things moved back to the Coeur d’Alenes. The WFM tried to organize the Bunker Hill Mine; the company employed Pinkerton agents to break up the effort. Several hundred miners proceeded to blow up the mill and destroyed other company buildings. In response, federal troops moved in and took more than a thousand people into custody, without charges, housing them in rough buildings that were not up to the cold conditions. Three miners died, and the animosity increased.

And the WFM became more radical. By 1901, union leaders were calling for a socialist revolution. And the violence, which had been aimed primarily at facilities, now targeted people. At Cripple Creek in November 1903, a superintendent and foreman were killed by a bomb. A nearby train depot was also blown up—13 strikebreakers died in the blast. National Guardsmen cornered a number of WFM members at the union hall in Victor, Colorado. Forty men were arrested and with hundreds of other strikers were deported from the region. The union was broken in Colorado.

But WFM leaders weren’t done. Bombs targeted the Colorado governor and two state Supreme Court justices. The attempts failed, but the union was undeterred. On December 30, 1905, former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg—who oversaw the response to the 1899 Coeur d’Alene strike—was killed by a bomb rigged to the front gate at his home. Union member Harry Orchard was arrested. He also confessed to several of the previous bombings and claimed that all had been ordered by WFM leadership.

Union President Charles Moyer, Secretary “Big” Bill Haywood and their colleague George Pettibone were tried in the Steunenberg murder. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow represented them; all three were acquitted. Orchard was convicted and spent the rest of his life in prison.

After that, the WFM suffered several setbacks in failed strikes. By the mid nineteen-teens, the union was ineffective. It made a bit of a comeback during the Great Depression, but its ties to the Communist Party dealt a solid blow in the 1950s. It was swallowed up the United Steelworkers Union in 1967. All that was left was a legacy of violence that shook the Old West.

Mark Boardman is the features editor at True West and editor of The Tombstone Epitaph.