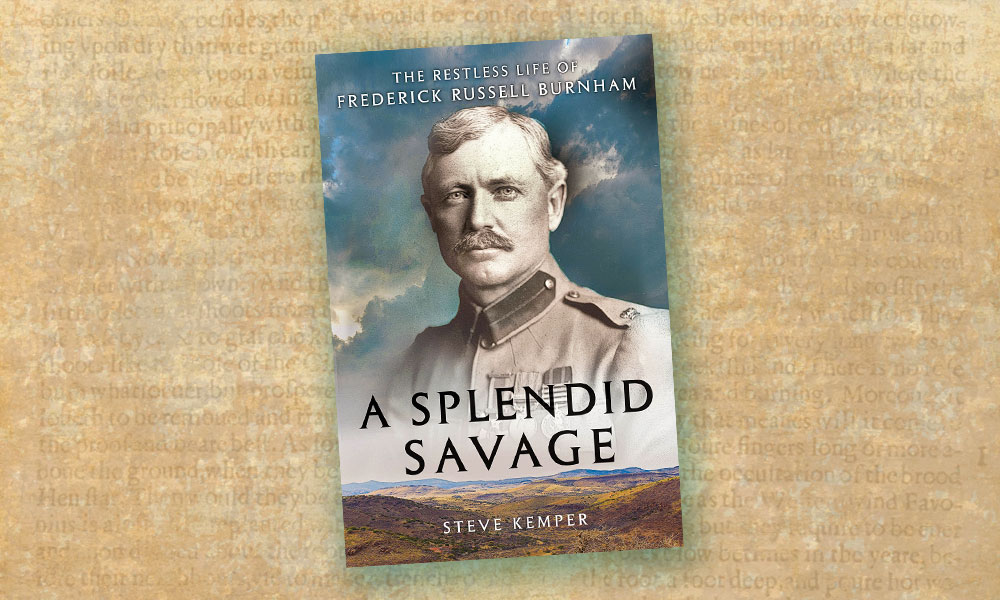

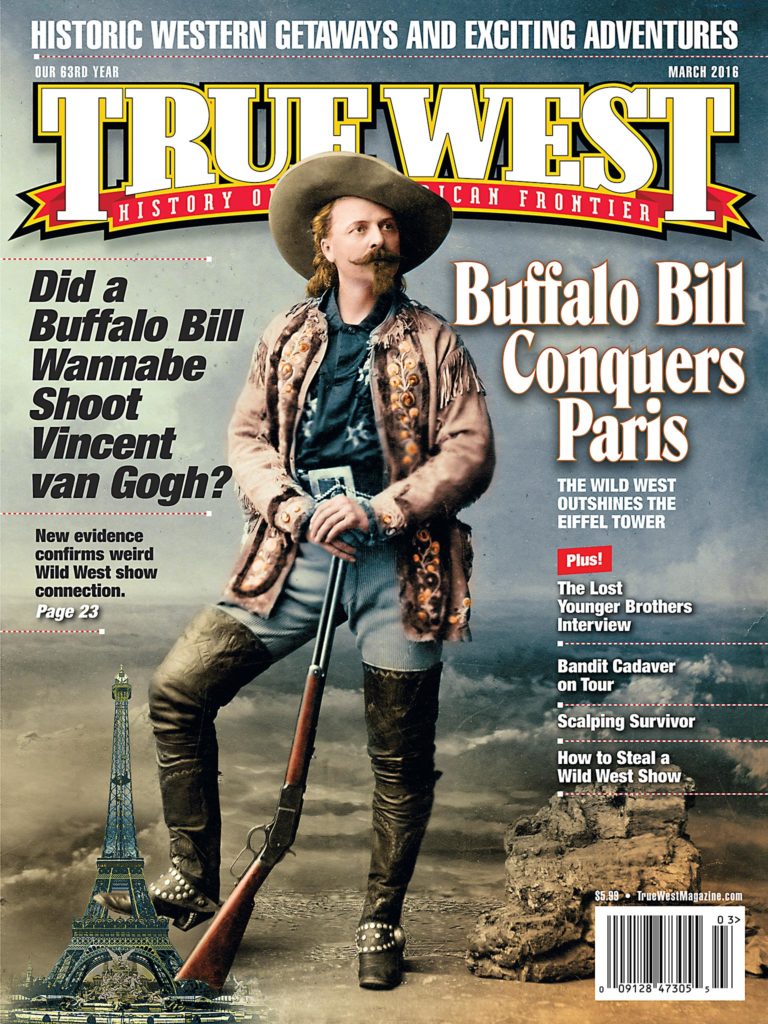

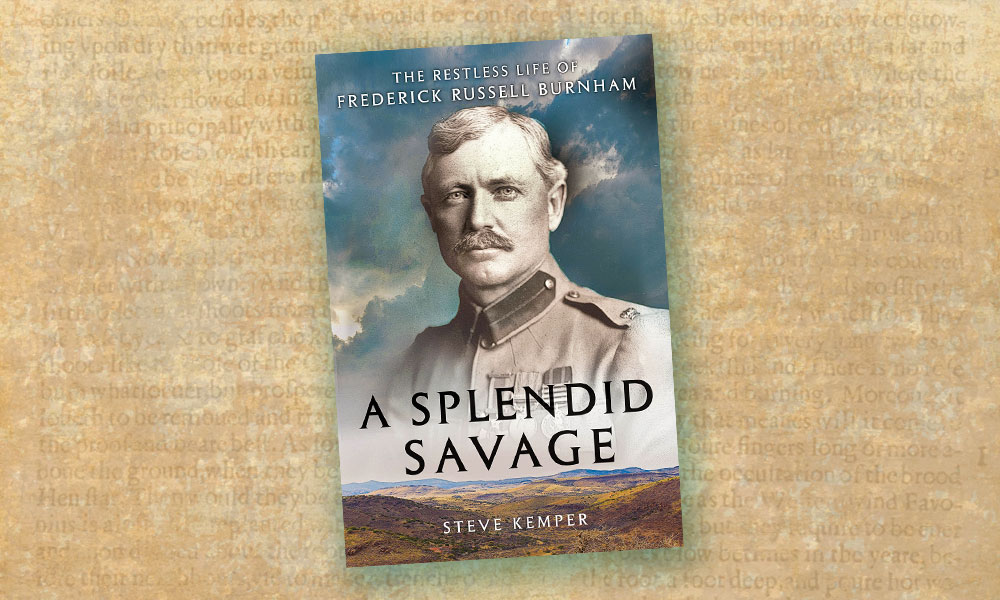

Since the earliest decades of Western settlements, authors have celebrated and iconized archetypal American heroes of the frontier. From Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett to Kit Carson and Buffalo Bill Cody, most of the lionized lived during an era of history well-defined through popular culture. Cody was born in the 19th century, early enough to live—and promote—an extraordinary life that began on the banks of the Mississippi in Iowa and later ride horseback across the silver screen in some of earliest Western silent-films of the 21st century. But, for every Boone, Crockett, Carson and Cody is an American adventurer of extraordinary character and accomplishment whose real life experiences were well known—and even inspired fiction—yet today are nearly forgotten. Steve Kemper’s A Splendid Savage: The Restless Life of Frederick Russell Burnham (W.W. Norton, $29.95) is a brilliant biography of a Westering man whose life would have been remembered by all who have studied and written about the West, except for the fact that the arc of his life, which reads like a Jack London adventure, stretched well beyond the borders of the American West in time and scope. According to Kemper, Burnham “constantly dreamed of a big strike, but also chased history’s leading edge, where the future felt up for grabs and values worth dying for were at stake. Burnham purposely skated these edges as a scout, prospector, pioneer, explorer, and imperialist soldier.”

Extremely well researched, with detailed end notes and selected bibliography, Kemper’s biography of Burnham should restore interest in a generation of American adventurers lauded by President Theodore Roosevelt (who sought to become one before and after the White House) and most recently, by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who popularized the type with Harrison Ford’s visage in Indiana Jones and Star Wars. Kemper writes that Burnham “resembled a comic-book swashbuckler, yet he often mocked such images as melodramatic clichés. As a scout, he preferred to sidestep danger, not rush into it. He survived so many extraordinary adventures because of intensive training and experience, not bravado.”

Burnham’s adoption of this practical philosophy began early on the Minnesota frontier and served him well as he came of age on the rugged edges of the American West in the 1870s and 1880s. After his father died in 1873 when Burnham was 12 years old, he chose independence and emancipation in wild and wooly Los Angeles, rather than moving with his mother and younger brother to be with family in Iowa. Burnham’s life soon embodied the popular adventure books he’d read as a young boy. In fact, unlike many of his peers who found just entertainment in the Western pulps, Burnham was led to be trained by former Indian scouts, and to cowboy, prospect, fight and scout his way across the West (including stints in lawless Globe and Tombstone, and as a scout in Crook’s Geronimo campaign) to become one of the most distinguished American scouts, soldiers and frontiersmen.

Burnham—forgotten by most who study and write about the Western United States, as well as by the comparative historians who study the similarity between American and European imperial development, settlement and military conquest of Africa, Asia and the Pacific—should actually be considered one of the most important and successful American frontier adventurers of his generation. Kemper’s eulogy of Burnham is succinct: “He was endlessly willing to set off into the unknown and start over. His natural habitat was the frontier, a place of escape and hope and violence.”

— Stuart Rosebrook