The groundbreaking star left a legacy of courage in Western films.

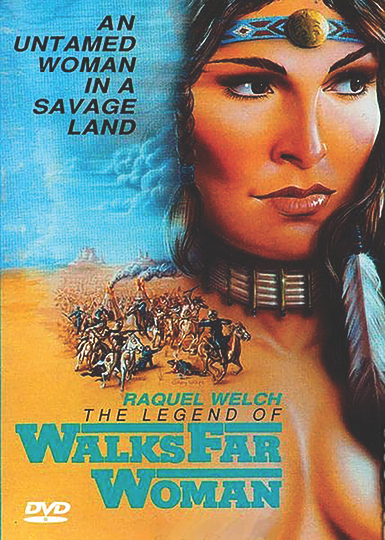

“I’m glad you’re writing about Raquel Welch because she shouldn’t be forgotten. She was an icon in American—and in world—cinema. She had a tremendous impact.” It was Nick Mancuso on the phone, Raquel’s leading man from her fourth and final Western, The Legend of Walks Far Woman, calling from a Paris movie set. “She was a marvelous person, a straight shooter. More than just an actress; she was an event in American cinema.”

The event that was Raquel Welch began life as Jo Raquel Tejada, the daughter of a Bolivian-born aerospace engineer and his Irish-American wife, who met in college, and raised their three children in San Diego. In her book, Raquel–Beyond the Cleavage, Welch wrote, “I was at the mercy of my turbulent family life,” retreating into a world of her imagination. “It seemed as if I had always wanted to be an actress.” She credited ballet study for her magnificent figure, and after success in beauty pageants, a stint as a TV weather presenter, and a too-young marriage and divorce, she found herself, and her son and daughter, in Hollywood.

Her first Western was a 1964 episode of The Virginian. She’s a saloon girl, and she asks Clu Gulager, “How about another drink, mister?”

“Later.”

“How about buying one for me?”

“Some other time.” That’s it, but she was filmed like a star, the camera starting on her legs, then doing a lovingly slow tilt up her figure to her face: perfunctory characters just don’t get that treatment. Two years later, she became a superstar, as a fur-bikinied cavegirl in One Million Years B.C., and in Fantastic Voyage as a gorgeous scientist who is shrunken to microscopic size and injected into a man’s bloodstream. Indeed, it felt at times like Raquel Welch had been injected into the bloodstream of the American male.

Feminine, yes, but not weak, either in herself or her characters; she kicked a male in the groin in 15 of her movies. “She was a complete actor; disciplined physically, mentally prepared, and she would stand up for herself,” Mancuso explains, “in the vein of old movie stars like Katharine Hepburn.”

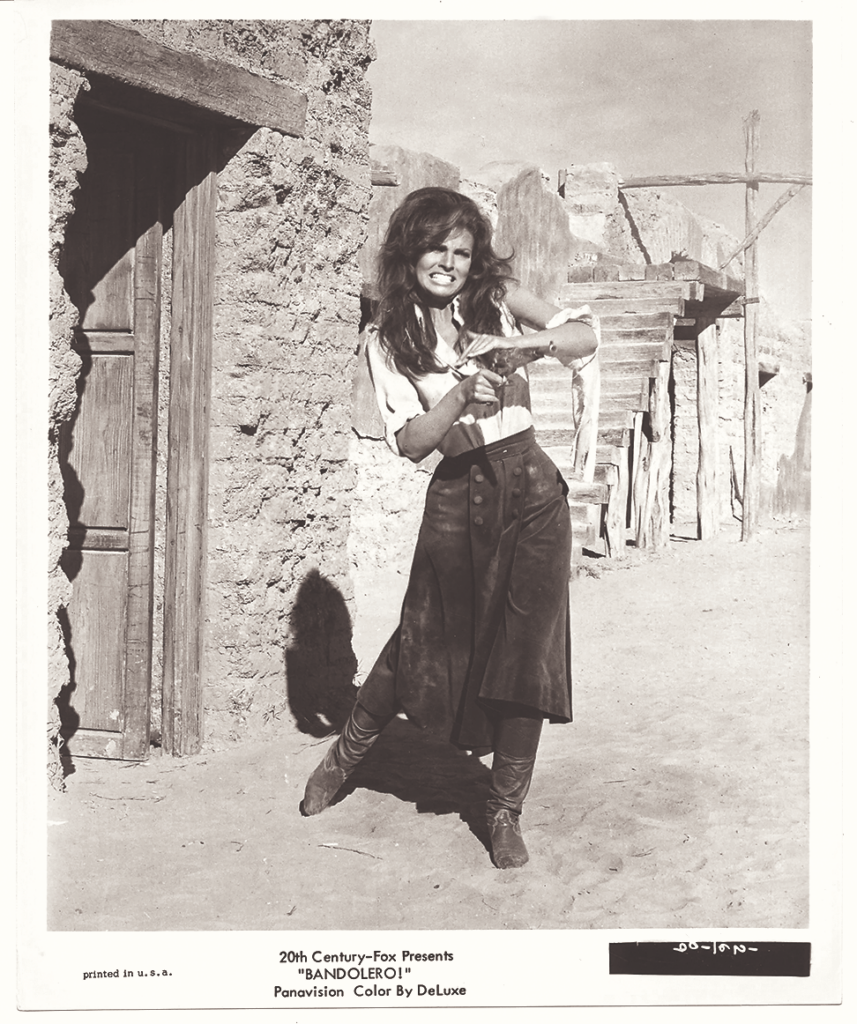

Her first starring Western was 1968’s Bandolero! in which she and rancher husband Jock Mahoney walk into a bank as Dean Martin and his gang are holding it up, and her husband is killed. Many men desire the widow, from sheriff George Kennedy to banker Denver Pyle, but they also underestimate her. When Pyle says she couldn’t possibly manage the ranch herself, she replies, “I was a whore at 13, and my family of 12 never went hungry.” And of course, she becomes a hostage of the outlaws. It’s a fine Western, tough and humorous, and with heart.

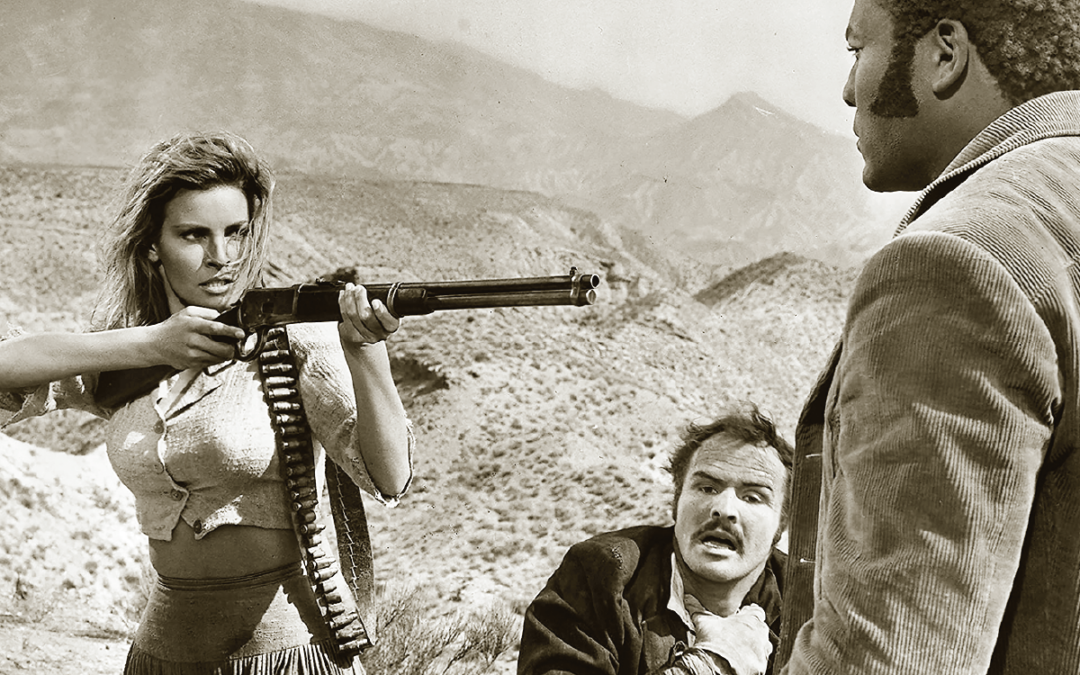

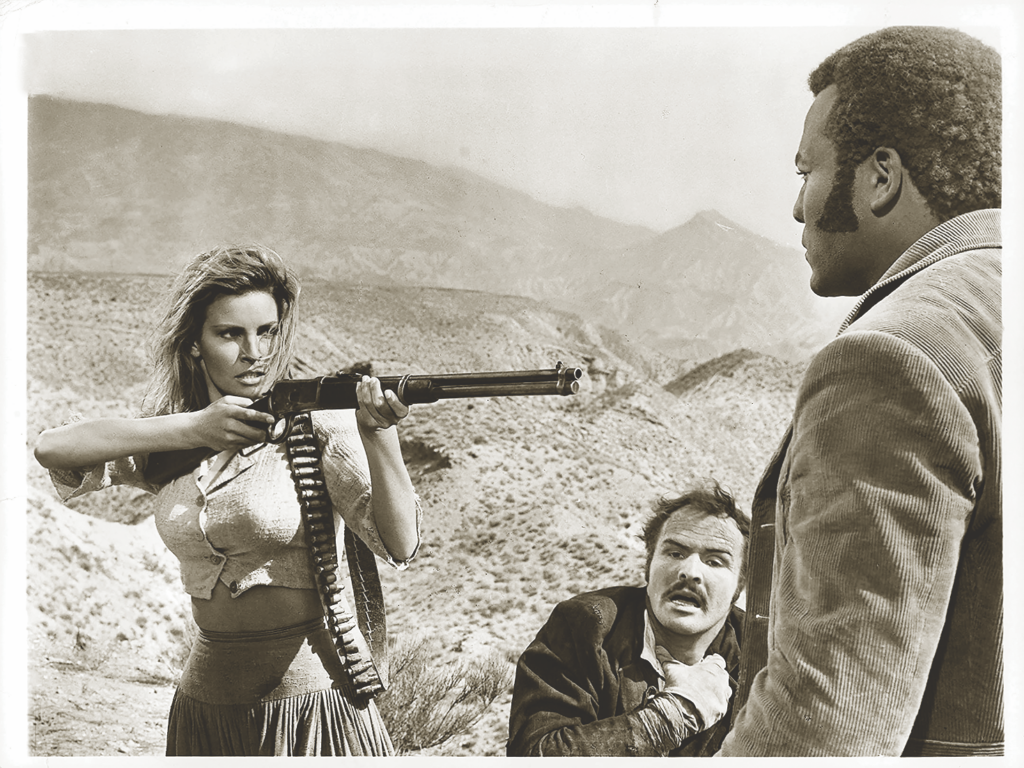

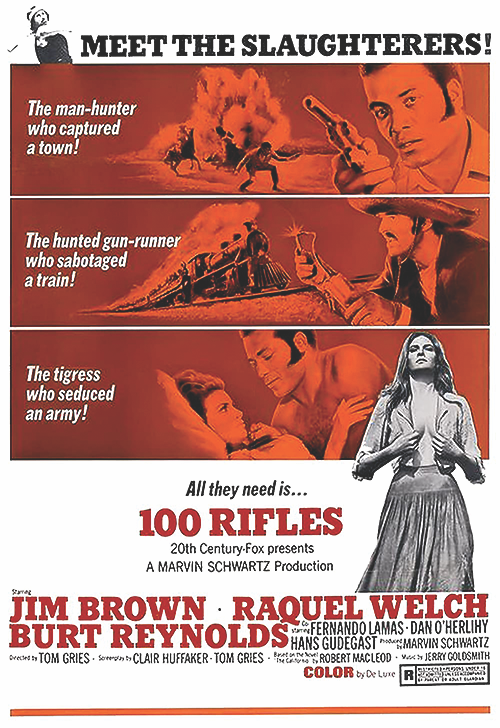

In 1969, Raquel went to Spain for 100 Rifles. The daughter of a Mexican revolutionary, when he’s executed, she assumes his position. Top-billed Jim Brown is an American cop looking for third-billed Burt Reynolds, a ne’er-do-well half-breed who’s robbed a bank to buy Raquel’s revolutionaries those rifles. Welch clashed with Brown, making filming their love-scene difficult, and she clashed with Reynolds as well.

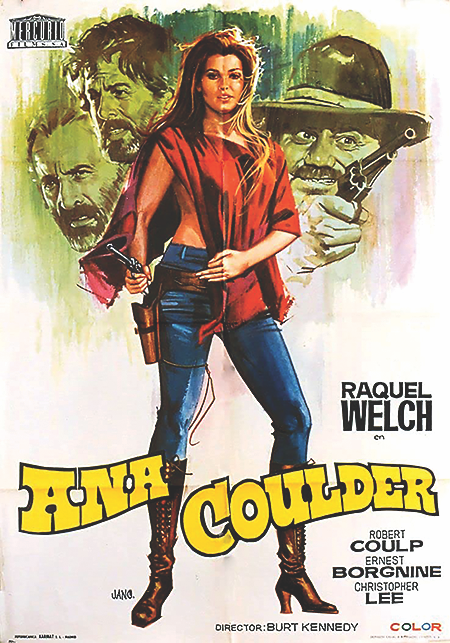

Back in Spain in 1971, Raquel starred in Hannie Caulder, which she co-produced. Once again, her husband is murdered by three fleeing bank-robbers—Ernest Borgnine, Jack Elam and Strother Martin—who gang-rape Raquel, torch her house and leave her to die. Escaping, she happens upon bounty hunter Robert Culp, who reluctantly teaches her to shoot, and she stalks and kills her attackers. Welch and Culp are wonderful together, as is Christopher Lee, in his only Western, as a gunsmith. The film’s biggest weakness is that the trio plays all their scenes together for comedy: it’s rather like seeing her assaulted by The Three Stooges. Raquel was still no pushover. As director Burt Kennedy told

C. Courtney Joyner in his book, The Westerners, “She shows up for work late, or at least the first assistant says she was, and as soon as he said, ‘You’re late,’ she hit him. Right on the jaw, just like John Wayne, and down he went.”

Nearly a decade later, Raquel produced her final Western, a TV movie, The Legend of Walks Far Woman. While all of her Westerns were good, this last may be her best, and certainly her most unusual: aside from Bradford Dillman’s mixed-race Singer, there are no non-Indian characters. Raquel plays the title character, mixed herself—Blackfeet and Sioux—who has killed the two Blackfeet who murdered her husband, and has been driven from her home. She settles in a Sioux village, and marries again. “I play her husband,” Mancuso says, “Horses Ghost. [We filmed] out in Billings, Montana, not far from the Battle of Little Big Horn. We reenacted many of the battle scenes.” In fact, their idyllic life falls apart when a concussion he receives during the battle leads to increasingly erratic, violent behavior.

Welch was as resilient as her characters. A year later, when she was fired from Cannery Row for unprofessional behavior on-set, she became unemployable in film. Instead, she got rave notices starring on Broadway in Woman of the Year. And she sued MGM, claiming, “What they did was use me to get financing for the movie, then they dumped me for Debra [Winger], which they’d been planning all along.” She was awarded $10 million, more money than Cannery Row’s entire box office.

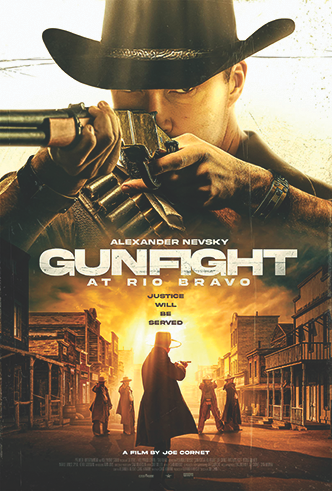

Blu-Ray REVIEW

GUNFIGHT AT RIO BRAVO

(Shout! Factory—$19.98) Moscow-born, three-time Mr. Universe Alexander Nevsky stars in this action-Western suggested by the life of Cossack-turned-Union Gen. John Basil Turchin. A marshal is transporting Hellhound-gang leader Ethan Crawley (Matthias Hues) to Rio Bravo, to hang. When they stop in sleepy Blind Chapel, awaiting Pinkerton reinforcements, Crawley’s gang attacks, and storekeeper Turchin must single-handedly defend the town. Director Joe Cornet’s fourth Western, although shot in Texas, recalls the international casts of 1960s Euro-Westerns: Russian, German, Italian and French accents are heard from the martial arts-heavy cast, plus one English accent that switches to a Southern drawl halfway through. The elegant cinematography outside of town, and the earnest enthusiasm of the cast, helps one to forgive the plot lapses and the often-glaring grooming and wardrobe errors.