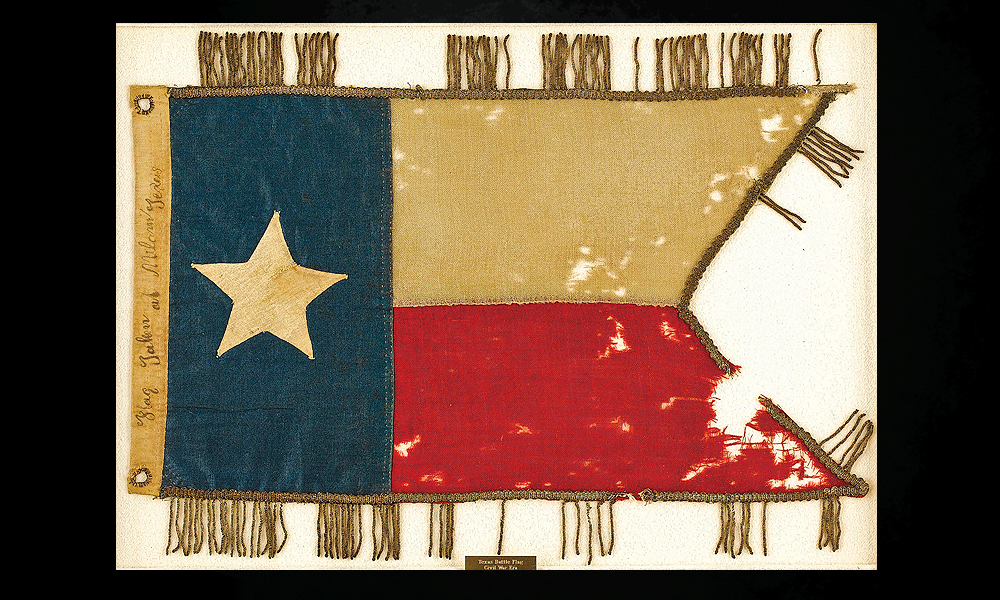

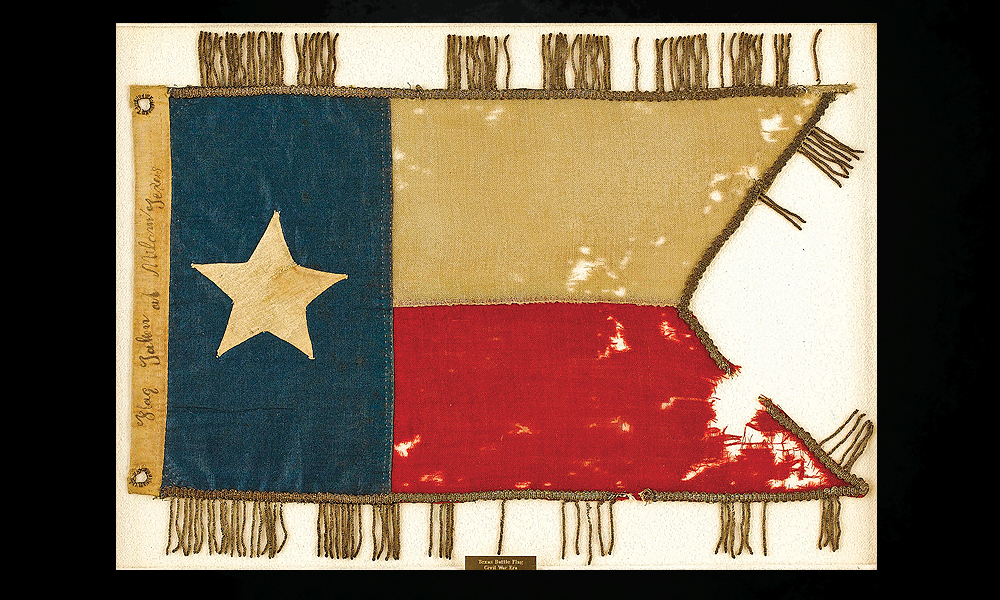

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 2007 –

Nearly six years after the Battle of San Jacinto seemed to solidify Texas independence, Mexico reconsidered—with force.

The Treaties of Velasco, signed in May 1836, gave official Mexican sanction to the new Republic of Texas—President Antonio López de Santa Anna signed it himself. But the rest of the Mexican government refused to ratify it, and Santa Anna later repudiated it. Mexicans and Texians skirmished over the next few years.

At the start of 1842, Gen. Mariano Arista proclaimed Texas could submit to Mexico or face the “persuasion of war.” Republic of Texas President Sam Houston took the threat seriously and sent spies to inform on Mexican troop movements. San Antonio citizens asked Texas Ranger John Coffee Hays to defend the city. He had about 120 men and a handful of cannon by early March.

Even so, citizens, fearing the worst, began abandoning San Antonio. The Mexican army captured Goliad and Refugio with nary a shot fired. The main force of 700 soldiers under Gen. Ráfael Vásquez reached San Antonio and demanded Texians surrender.

On March 5, Hays, ignoring the option of surrendering, took a vote of the men—should they fight or retreat? The vote was 54-53 in favor of leaving. After destroying some buildings and powder and arms they could not carry, the ragtag group headed 35 miles east to Seguin. The Mexicans entered San Antonio and found a ghost town.

They looted the city for a couple of days. Vásquez and Santa Anna had made their point: nobody could stop Mexico from invading Texas. Or so they thought, as they headed back into Mexico.

The Vásquez incursion was just a start. Santa Anna was determined to get the lost land back and to avenge his humiliation at San Jacinto. His forces undertook hit-and-run raids into south Texas in June 1842.

On September 11, some 1,500 Mexicans and Indians under the direction of Gen. Adrián Woll retook San Antonio. Six days later, Woll and his men chased a group of Texians to a site near Salado Creek, where more than 200 militia, led by Capt. Mathew Caldwell, met them head on. Although vastly outnumbered, the Texians won that day.

But a tragedy spoiled their glory. Captain Nicholas Dawson was leading 53 reinforcements near San Antonio when several hundred Mexican cavalry attacked. The Texians surrendered; the Mexicans opened fire, killing 36. Fifteen others were taken to Mexico, while two men escaped.

Some Texians followed the Mexicans south, attempting their own counter-invasion. The Mier Expedition ended up a dismal failure, capped by the “Black Bean Incident,” where Texians were executed.

The Mexican threat to Texas independence was not solved until the battles of the Mexican-American War ended in the fall of 1847—and by that time, Texas had been a state for nearly two years.