Pecos, Texas, wouldn’t exist if not for the shape of the Pecos River. Near where the town would come to be, the deep, twisting gorge narrowed to allow the crossing of horses, wagons and cattle being driven to market.

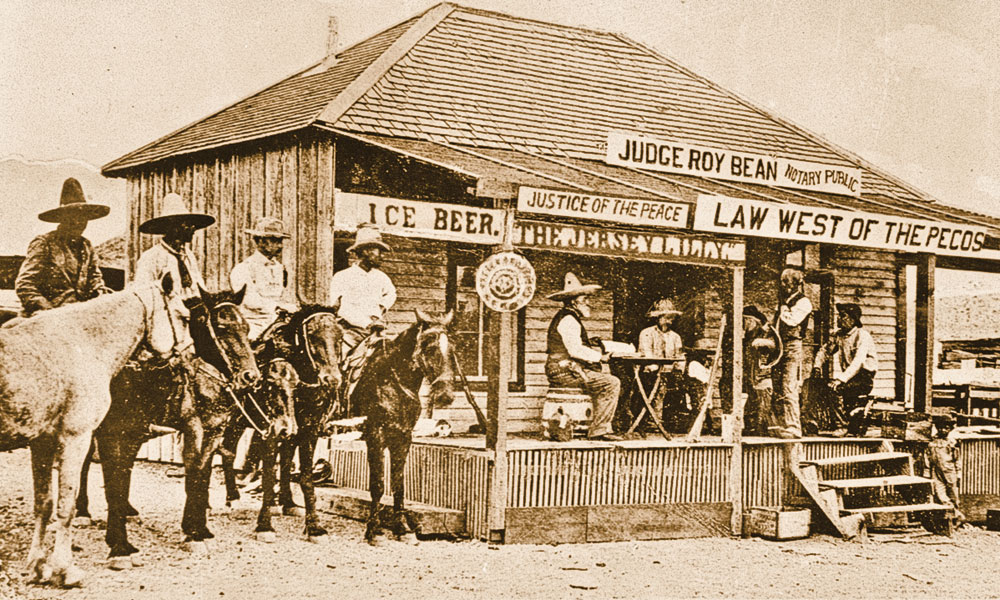

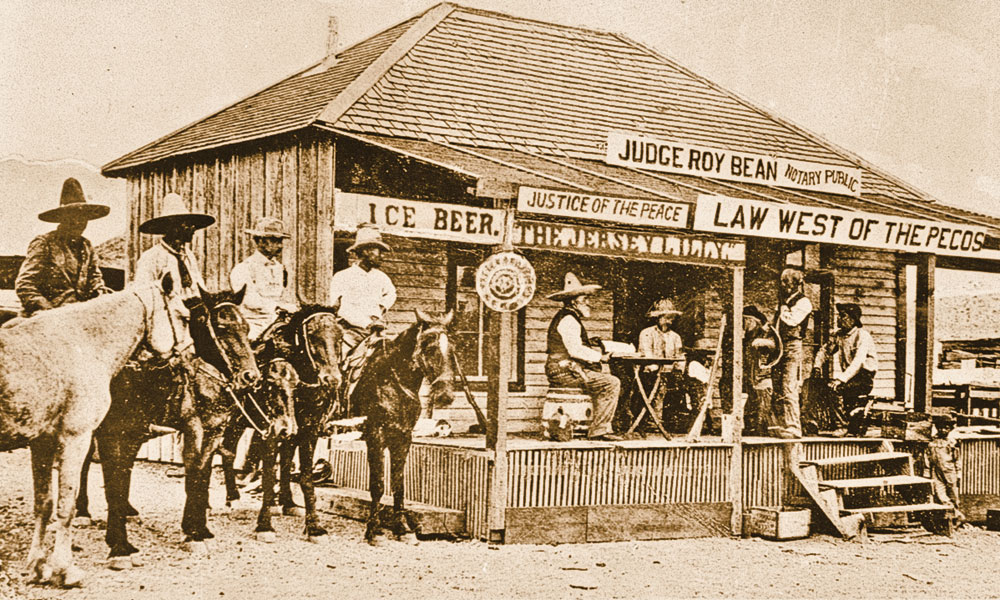

Beginning about 1873, a crossroads settlement sprouted on the west Texas prairie. Its main activities were “ranching, farming, drinking and shooting at each other,” jokes Debbie Thomas, former director of the West of the Pecos Museum. “But it really was a wilderness. If you were running from the law, this was the place to be.”

Beginning about 1873, a crossroads settlement sprouted on the west Texas prairie. Its main activities were “ranching, farming, drinking and shooting at each other,” jokes Debbie Thomas, former director of the West of the Pecos Museum. “But it really was a wilderness. If you were running from the law, this was the place to be.”

Modern visitors find a town of 9,000 that holds fast to its frontier past. The West of the Pecos Rodeo in June offers four nights of cowboy action at Buck Jackson Arena. It also provides a whiff of controversy by dubbing itself the West’s oldest rodeo, begun in 1883.

The claim causes indigestion in Western towns that make the same boast. The matter boiled over in 1985 when the board game “Trivial Pursuit” named Prescott, Arizona, as the place where rodeo was formalized, and Pecos threatened to sue, according to The New York Times. “Trivial Pursuit” held firm and so did Pecos.

We’ll back away from that fight, hands raised. Suffice it to say, proud Pecos makes a strong case and dearly loves its rodeo.

The town is also partial to cantaloupe. Some call the locally grown variety the sweetest in the world. The Night in Old Pecos Festival takes place in July, along with a show featuring a variety of cantaloupe-based foods—brownies, jelly, smoothies, soup.

Pecos Mayor Venetta Seals has won best-in-show for her cantaloupe salsa, made with sweetened jalapeño. Oh, mama! If you visit in May, be alert for sidewinders selling knockoffs from trucks on Highway 285.

“Remember that Pecos cantaloupes don’t come in until late June or July,” says Seals. “Our cantaloupes are so good we don’t like imposters.”

The food show is usually held at the West of the Pecos Museum, at Forest and Cedar streets. The building started as the Number 11 Saloon, with bedrooms upstairs. A third floor was added in 1904, when it became the Orient Hotel.

The museum today is housed in the old Orient—a three-story, red sandstone structure with 50 rooms of exhibits and artifacts.

Director and Curator Dorinda Millan says visitors love seeing the Number 11 Saloon’s ornate bar and huge liquor cabinet, bullet holes from past dustups, and the pressed-in ceilings in the lobby and hotel dining room.

The park next door has the grave of wild man Clay Allison. He called himself a shootist rather than gunfighter, but his enemies failed to appreciate the distinction.

For a terrific day trip, drive 75 miles to Fort Davis National Historic Site. One of the frontier’s best-preserved forts, it once had more than 100 structures and quarters for 400 soldiers. It operated from 1854 until 1891.

Today, five buildings have been restored. Visitors step inside the barracks to see iron bunks, footlockers, carbine racks, clothing and other artifacts from when Buffalo Soldiers were headquartered there. See the authentic commanding officers’ quarters, furnished circa 1882.

Fifty-three miles from Pecos, visit the Annie Riggs Museum in Fort Stockton. The 13-room territorial adobe with wraparound verandas has a video on fort history and artifacts like a cast-iron bed from Sears and Roebuck. Cost: $6.75, including freight.

The museum, originally a boardinghouse, has Annie’s rules still posted. No spitting on the floor, please.

For a break from the dry prairie, drive to the incongruous oasis of Balmorhea State Park. When the Apaches watered horses there in the 1840s, the area was called Mescalero Springs. Mexican farmers named it San Solomon Springs.

The crystal-clear water rises through natural faults at 15 million gallons per day, the temperature steady at 72 to 76 degrees. The desert wetland makes a delightful getaway for swimmers, hikers, nature lovers, even scuba divers.

Leo W. Banks is an award-winning writer based in Tucson. He has written several books of history for Arizona Highways.