– Courtesy NPS.gov –

If William Clark and Meriwether Lewis are the Yankees and Dodgers of American West explorers, then Zebulon Montgomery Pike has to be the St. Louis Cardinals.

I can’t believe I just wrote that. I hate the Yankees, and I rarely root for the post-Brooklyn Dodgers or the Cardinals, though it’s hard to find a better baseball town than St. Louis (Kansas City still has better barbecue).

Zeb Pike seemed an unlikely choice to lead an expedition up America’s best-known river (or have a Colorado mountain named after him). Born in Lamberton, New Jersey, in 1779, Zeb came from a sickly family. Four of his siblings died young; three others contracted tuberculosis. Zeb’s soldier father moved the family west after the Revolutionary War to Pennsylvania and Ohio, where Zeb joined the Army at age 15. General James Wilkinson took a liking to the boy, promoting Zeb to lieutenant, then summoning him to St. Louis to send him up the Mississippi.

party to locate the source of the Mississippi River. Pike’s company

left the fort in August 9, 1805, and returned on April 20, 1806.

– Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, S-NPG_80_15, Smithsonian Institution –

Our river trip begins in St. Louis, too, with history stops at Jefferson Barracks Park, Gateway Arch National Park and, of course, Fort Belle Fontaine. On August 9, 1805, Zeb and 20 others left the new fort, the first U.S. military installation west of the Mississippi River (now a county park). Zeb didn’t know it at the time, but when they launched that 70-foot keelboat, he was also launching his way to fame.

Wilkinson’s reasons for ordering the mission are unclear. Zeb’s orders were basically to find the river’s source, make notes of distances and geography, investigate the fur trade, find possible sites for military bases, make peace with Indian tribes and collect plant and animal specimens. But Wilkinson didn’t have a sterling reputation. Historian W.E. Hollon called Wilkinson “Vain, bombastic, and incompetent” and “a master of petty treason with a gift of scandal.” If Wilkinson played baseball, he would have been a Houston Astro.

– Courtesy Gateway Arch Park Foundation –

My major-league baseball comparison doesn’t quite work, but not because the game wasn’t around in 1805. Major league? This appears to be Class A ball. No one thought to assign a doctor to this corps. Or an interpreter to make those Indian negotiations productive. Zeb did have a device to determine latitude, along with a watch and thermometer—all the scientific instruments one needs for such an endeavor. He brought along some hunting dogs and, better yet, whiskey. Best guess is that the government spent roughly $2,000 to equip Zeb’s crew, just a tad less than the Kansas City Royals’ annual payroll.

Zeb’s men had to drag that keelboat over sandbars on their way north. And Zeb was not the patient type. Near present-day Muscatine, Iowa, after losing two of his hunting dogs, Zeb left behind the dogs—and the two soldiers who volunteered to look for them. Helped by a Scottish trader and an Indian, the men caught up with Zeb near Dubuque, Iowa. The dogs remained AWOL.

While much of Zeb’s trip is overlooked today, Old West history flows along both shores of the river.

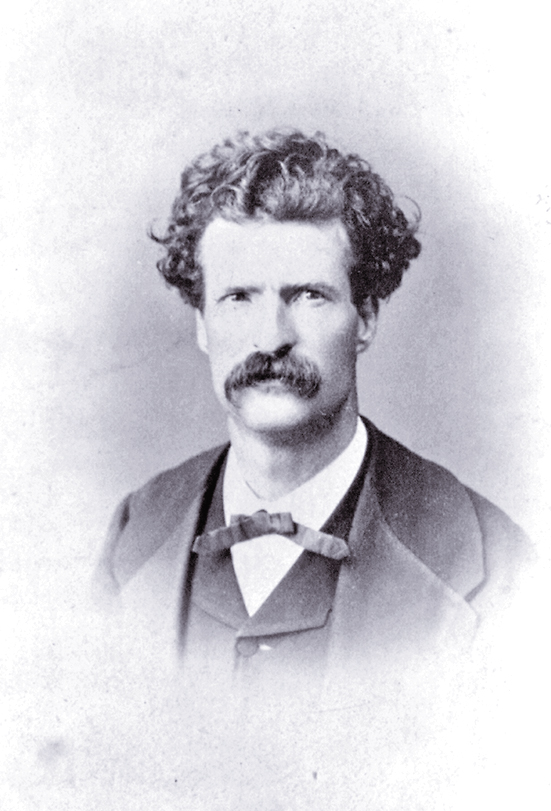

–Mark Twain Statue Photo by Johnny D. Boggs/Mark Twain Photo Courtesy Library of Congress –

There’s Hannibal, Missouri, (Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum, Hannibal History Museum), because who can travel the Mississippi without thinking about Samuel Clemens? There’s Nauvoo, Illinois, (several Latter-day Saints sites), once called the “Kingdom of Pike.” There’s Fort Madison, Iowa, home of Old Fort Madison, established in 1808 to protect the new Louisiana Territory.

There’s LeClaire, Iowa, where Zeb’s boys camped April 24, and where a historical marker commemorates pre-Buffalo Bill William F. Cody’s birth in 1845. The farmhouse Cody’s father built in 1847 has been restored near Princeton, and, to keep our baseball theme going, the Field of Dreams movie site is a tad inland near Dyersville.

Two miles south of McGregor, Iowa, Pikes Peak State Park brings us back to our subject. Pike found this spot at the mouth of the Wisconsin River in September 1805. Iowa’s Pikes Peak, by the way, is a 500-foot bluff—call it 1,112 feet in elevation, a tad under Colorado’s 14,114-feet summit. Pike recommended the location as a possible military site, but the Army picked nearby Prairie du Chiene, Wisconsin, where the Fort Crawford Museum honors the two forts operating here from 1816 to 1856.

When Zeb reached present-day Minneapolis-St. Paul (Fort Snelling State Park, Minnesota History Center), he noted that the hills, valleys and trees were “sometimes interrupted by a wide extended plain.” With snow falling in October, Zeb’s party stopped near Little Falls, Minnesota (Charles A. Weyerhaeuser Memorial Museum) to build a winter stockade. Sleds and legs took the party north to Brainerd (Crow Wing County Museum) and Grand Rapids (Judy Garland Museum) and finally, on February 1, Zeb discovered the Mississippi’s source at what is now Cass Lake.

of the Rock and Mississippi rivers near the Quad Cities of Illinois and Iowa.

– Stuart Rosebrook –

Only…the Mississippi’s source is 25 miles west at Lake Itasca. Well, it’s not like Zeb was good at finding where rivers begin.

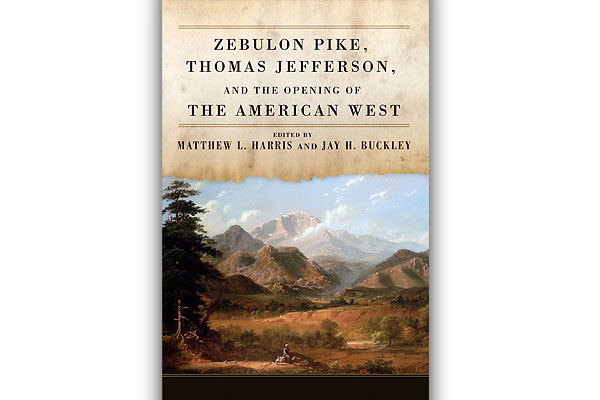

“Where do the Mississippi and Red River begin? That’s what Zebulon Pike was ordered to find out in 1805 and 1806,” Western Writers Hall of Fame member Will Bagley says. “He got close but didn’t find either. He did find the sources of the South Platte, built a fort on the Rio Grande and discovered Grand—now Pikes—Peak…before he disappeared into the shadow of his fellow adventurers Lewis and Clark.”

The boys began their return home on April 8, arriving three weeks later, after covering more than 2,000 miles in 264 days.

– Courtesy TravelIowa –

“Although his mission was mostly successful, he failed in locating the exact beginning of the Mississippi,” says James A. Crutchfield, another historian in the Western Writers Hall of Fame. “He did, however, obtain from the natives a large tract of land surrounding the Falls of St. Anthony, which eventually became the site of the massive Fort Snelling, and later the cities of Minneapolis-St. Paul.”

– Johnny D. Boggs –

Zeb “would be little remembered today as an explorer if he were judged solely by the Mississippi expedition in 1805-6,” Hollon wrote in a 1949 article for The Wisconsin Magazine of History. But Zeb’s life on the Mississippi helped him in the end.

Says Crutchfield: “The leadership, wilderness and negotiating skills that Pike developed on this nearly nine-month-long journey well prepared him for his second foray into the Western wilderness—to the frontier of New Mexico and beyond—the mission for which he will always be remembered and which ensured his legacy as one of the foremost of American explorers.”