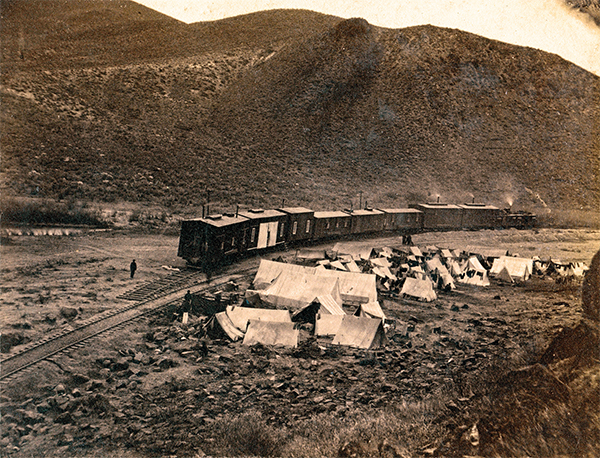

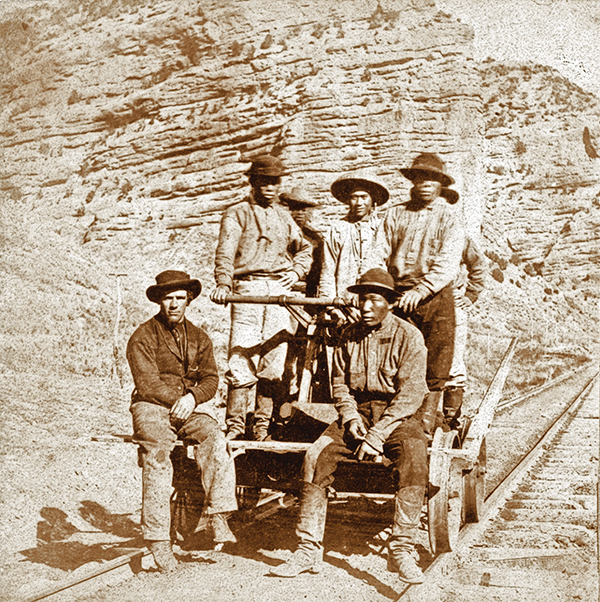

— Chinese Nevada Central Pacific Railroad Camp Courtesy NPS.gov —

Without the back-breaking labor of Chinese immigrants the pivotal event in the development of the nation—the laying of the last rail and placing of the golden spike joining the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads—would not have happened as

it did. And, yet, just two Chinese workers are visible in a well-known image of the

May 10, 1869, railroad celebration at Promontory, Utah.

This small representation at the Golden Spike celebration contradicts the Chinese workers’ actual contribution. Some 12,000 Chinese laborers did the strenuous work of building the grade for the Central Pacific line. They worked at a grueling pace, dug 13 tunnels through the Sierra Nevada range and, on one day, laid 10 miles of track as the Central Pacific raced to conclude its work in Utah. That feat alone set a record for railroad construction, never paralleled in the 19th century.

Much of their work was related to the grading of the route; other workers did most of the track laying.

While they are not prominently included in the photos of the end-of-track celebration, the Chinese were recognized for their effort. A report published in San Francisco just five days after the golden spike and champagne toasts noted, “J.H. Strobridge, when the work was all over, invited the Chinese who had been brought over from Victory for that purpose, to dine at his boarding car. When they entered, all the guests and officers present cheered them as the chosen representatives of the race which have greatly helped to build the road…a tribute they well deserved and which evidently gave them much pleasure.”

Sacramento to Reno

— Courtesy The Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress —

To journey today along the route of the Central Pacific Railroad, begin at the California Railroad Museum in Sacramento, with its variety of rolling stock and extensive exhibits. From Sacramento drive Interstate 80 east into the Sierra Nevada. In an automobile the route travels a slight incline from Sacramento through Roseville and then makes a more precipitous descent toward Reno, Nevada.

— Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections —

The Sierra Nevada summit was the highest point on the Central Pacific line and no train could negotiate such a grade, so Lewis Clement engineered a route through the mountains. A combination of black powder, nitroglycerin and the hard labor of the Chinese workers allowed Clement to punch tunnels through the granite. One of the more amazing engineering marvels of the Central Pacific Railroad construction is that the Chinese railroad crews worked from both the west and east sides of the mountain range, and met in the middle with an unparalleled precision.

To carve this route across (and through) the mountains, the Chinese lowered themselves from ropes slung from the top of the mountains’ peaks. Then they drilled and packed black powder charges into the rock. Once they carefully laid their charges and lit the fuses they quickly ascended their ropes to avoid the explosions. The combination of this dangerous construction method and brutal winter weather often proved deadly.

It took two years to build the first 50 miles of Central Pacific track, but by the summer of 1868—when the Union Pacific was pushing across what would become Wyoming Territory—they had successfully negotiated the Sierra and descended to the Great Basin.

Across the Nevada Desert

Our route follows I-80 to Reno and parallels the Central Pacific route through Winnemucca, Battle Mountain, Elko and Wells, Nevada. Many overland wagon train travelers, following their noses to the California goldfields starting in 1849, used this route. Today you can make the journey by automobile, or take the Amtrak California Zephyr to experience the rails for yourself.

— Courtesy Humboldt County Museum, Winnemucca, Nevada —

In Nevada take a ride on a 1905 steam locomotive, the Virginia & Truckee #25, or one of the other cars at the Nevada Railroad Museum in Carson City. The steam trains run most weekends during the summer and into October with some weekend operations in November and December.

The Central Pacific rails reached Winnemucca on September 16, 1868. The Champion was the first locomotive into town. There was no celebration at Winnemucca then as the grade work and track laying quickly continued to the east. By November the railroad was completed through Humboldt County. The first passenger train, consisting of four cars, reached Winnemucca, on May 11, 1869, just days after the transcontinental route was complete.

— Courtesy TravelNevada —

The C.P.R.R. train carried the Railroad Commissioners and the president and vice-president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company. The Humboldt Register described the celebration in Winnemucca upon conclusion of construction as follows: “We had a big time in Winnemucca celebrating the completion of the railroad. Firing guns, blowing whistles, ringing bells, ‘driving spikes’ and drinking champagne, was the order of the day. Some of the boys are celebrating yet.”

At the Humboldt Museum in Winnemucca, see a collection of early vehicles, including horse-drawn wagons and early automobiles. To learn about the earlier wagon migrations across the region, visit the California Trail Interpretive Center just west of Elko.

Salt Flats to Promontory

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

The highway route diverts from the original line of the Central Pacific, as I-80 stretches across Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats and into Salt Lake City. This also parallels the route of today’s rail line across Utah and Nevada. The original railroad bed cut farther to the north. You can see where the Central Pacific and Union Pacific rails met in 1869 by traveling north on Interstate 15 from Salt Lake City to Ogden and Brigham City, then taking Utah Route 83 to the west. This highway and another spur road, will give you views of the original grade, cuts and fills along the Central Pacific route, before reaching Promontory and the Golden Spike National Historic Site.

The Chinese Legacy

The first Chinese workers to help build the Central Pacific railroad began in 1865 and by 1867, crews of 8,000 men were building tunnels, while another 3,000 assisted the track-laying crews. Blasting through granite to build tunnels and roadbeds, they faced challenges including frequent snowdrifts, dangerous avalanches, illnesses and accidents. They suffered from racism, unfair wages and other discriminatory practices prevalent at the time. Through the construction period they endured anti-Chinese protests and more violent acts.

When the Chinese laborers went on strike in 1867, demanding a raise in pay from $35 to $40 a month, management responded by cutting off food trains, bringing an end to the strike.

The Central Pacific kept no records of deaths among the Chinese workers who built their line; estimates are widely disparate, from as few as 50 to as many as 1,200, or roughly 10 percent of the workforce. Their contribution—in many cases life sacrifices—changed the nation forever on May 10, 1869, the day the rails were linked.

Candy Moulton hangs her hat at her home near Encampment, Wyoming, when she is not adventuring somewhere in the West.