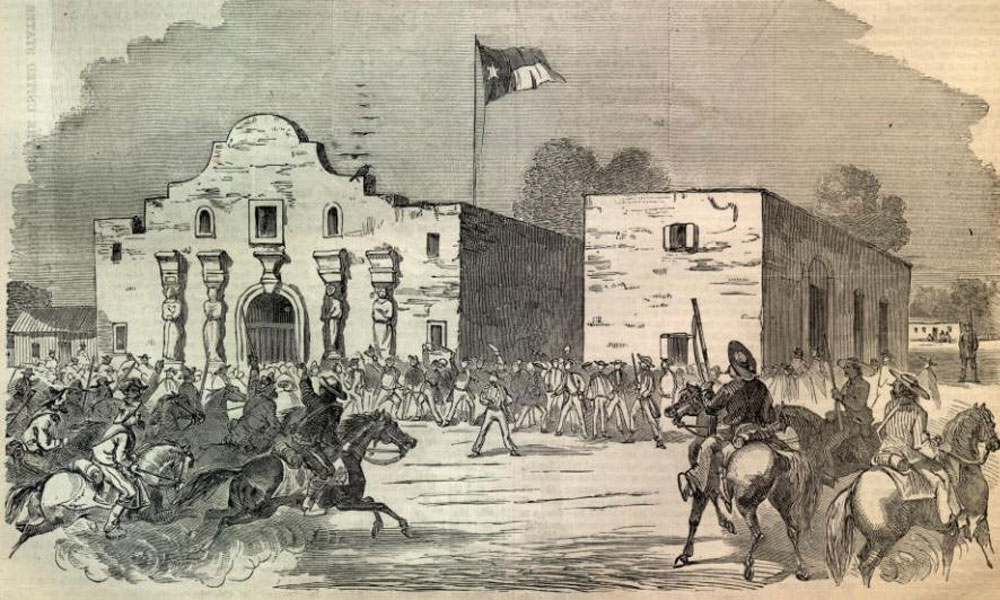

— “Battle of the Alamo” by Percy Moran, ca. 1912, Courtesy Library of Congress —

We remember the Alamo siege and battle for the men who died there. Not as well remembered are their families who endured the thirteen-day siege and final battle alongside them. Gunfire had barely ceased in and around the Alamo on the morning of March 6, 1836, when Mexican soldiers gathered a group of traumatized, frightened women and children and led them from the fort.

Facts about the Alamo survivors have blurred over the years due to conflicting accounts, editorializing by interviewers, failing memories and some hostilities among certain survivors. Most of the women and their children endured the battle in a back room of the Alamo church. A few sheltered in other parts of the fort. Most were lucky enough to have lived through the early morning fight.

— All Photos Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted —

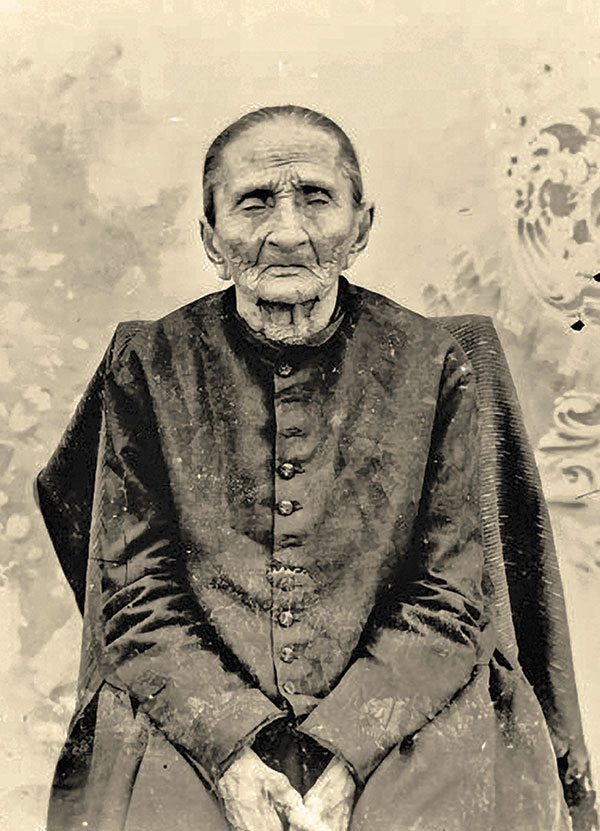

Susanna Dickinson receives the most attention as a survivor of the Alamo. Many early newspaper articles and histories incorrectly recorded her as the sole survivor. Wife of artillery officer Almeron Dickinson, she survived the battle with her young daughter Angelina. Susanna left a number of conflicting accounts of the Alamo over the years, which keep Alamo historians scratching their heads to this day. She remembered her husband rushing into the room to inform her that the Mexicans were inside the walls. He implored her to save their child if the enemy spared her. He returned to the fight and she never saw him alive again. In a later account, she told of 17-year-old Galba Fuqua of Gonzales running into her room to convey a message to her. Unfortunately he could not speak, since a bullet had broken his jaw. After several attempts he rushed back to the battle.

Susanna left stories of seeing one or more of the Alamo garrison, and maybe two young boys, bayoneted to death after they sought shelter in the non-combatants’ room. Names and numbers vary in her accounts. She may have witnessed her husband’s body being bayoneted by Mexican soldiers, and may have been wounded in her calf by a stray bullet as she left the Alamo church after the battle. She, along with Joe, the slave of Alamo commander William Barret Travis, later verified the news of the Alamo’s fall to General Sam Houston.

Susanna lived out her life in Texas, marrying four times. She and her last husband, Joseph W. Hannig, prospered in real estate and other enterprises in Austin in the 1870s. She died there on October 7, 1883, at the age of sixty-eight.

Ana Salazar Esparza, wife of Pvt. José Maria (Gregorio) Esparza, along with four, possibly five, children sheltered in the same room of the Alamo church as Susanna Dickinson. The Esparzas entered the Alamo at twilight on the first day of the siege. Her story comes to us from several interviews given years later by her oldest son, Enrique. As with the Dickinson accounts, the stories conflict, and it remains unclear whether the Esparzas had an infant daughter with them in the fort. Enrique mentions an infant in some accounts. In others he mentions an older, 10-year-old half-sister, Maria de Jesús Castro, by his mother’s previous marriage to Victor de Castro. Besides Enrique and Maria, Ana had the care and safety of her other sons, Manuel and Francisco, and possibly the infant daughter, on her mind throughout the 13-day siege.

Mexican soldiers took Ana and her family along with most of the other survivors to the house of Ramón Músquiz in San Antonio and placed them under guard. At about eight o’clock in the morning Ana defied the guards and rummaged about the Músquiz house for food to feed her hungry children and other survivors. A very jumpy Señor Músquiz convinced her to stay put and provided food for his guests.

It is said that after the release of her family, Ana returned to her home and wept for many days. She passed away on December 12, 1847.

Juana Navarro Perez Alsbury; her younger sister, Gertrudis Navarro; and Juana’s 11-month-old son, Alejo Perez Jr., probably entered the Alamo under the protection of Jim Bowie, they being the cousins of his late wife Ursula Veramendi. Juana, who had recently lost her first husband and possibly a young son Encarnación to cholera, married Doctor Horace A. Alsbury in January 1836. Bowie sent Alsbury from San Antonio on a scouting mission or to drum up reinforcements for the garrison.

During the siege Juana and her small family occupied a room along the Alamo’s west wall, apart from the other women and children. As Mexican troops cleared room after room on the morning of battle, Juana directed Gertrudis to open their door to show the soldiers that women and children were present. A soldier grabbed Gertrudis’s shawl and pursued her into the room, demanding her “money or her husband!” She cried that she had neither as the soldiers ransacked the room taking money and personal possessions left there for safekeeping by some of the Alamo’s officers. Juana described a man named Mitchell running into the room to protect her and her sister. She also recalled a young Tejano defender run in seeking shelter. Both died by bayonets before her eyes.

A Mexican officer entered the room and took the terrified young ladies and baby outside where the battle raged. As things quieted they cautiously made their way back to the room but were hailed by a Mexican soldier, the brother of Juana’s late husband, who took them into his protection.

She and Horace Alsbury reunited in May 1836, following the Texans’ April 21, 1836, victory over Santa Anna at San Jacinto. Alsbury died in the Mexican War in 1847 and Juana married again, this time to her first husband’s cousin, Juan Perez. She passed away on July 25, 1888.

Her son, Alejo Perez, holds the distinction as the longest living known survivor of the Alamo battle. He became a member of the San Antonio Police Department, lived until 1918 and died at the age of 83.

Nineteen year-old Gertrudis Navarro survived the battle with her sister. Five years later she married José Miguel Felipe Cantu, and lived the next half-century in San Antonio. She died in April 1895.

Forty years after the Alamo’s fall, Susanna Hannig (Dickinson) reported somewhat bitterly that Juana and Gertrudis escaped to the enemy during the siege, about two days before the battle, and betrayed the condition of the garrison. This accusation has never been verified.

Concepción Charlí Gortari Losoya had lived in the southwest corner of the Alamo compound in her younger years. Her son, José Toribio Losoya, served in the Alamo garrison. She, her younger son Juan and daughter Juana Francisca may have entered the Alamo under the protection of the garrison’s Quartermaster Eliel Melton, Francisca’s husband. Toribio’s wife and child found shelter in town upon the Mexican army’s arrival.

Enrique Esparza, entering the Alamo with his family, remembered Francisca Melton drawing circles on the ground with an umbrella. The image remained vivid in his memory since he had seen very few umbrellas. Eliel Melton, a merchant before his military service, possibly had access to such exotic objects as umbrellas. Esparza added that following the battle and before the survivors were brought before Santa Anna, Francisca—through her brother Juan—asked Ana Esparza not to reveal to Santa Anna that she had married an American. Ana reassured her and told her not to be afraid. Esparza always remained a bit indignant about this since he felt that Francisca looked down on his mother and never acknowledged her in the past.

He remembered a Victoriana de Salinas and three small daughters as surviving the battle but provided no further details on this family or why they were in the Alamo. He only stated that he remained acquainted with two of the girls in later life.

Petra Gonzales, an older woman known as Doña Petra to Esparza, may have been a relative of Ana Esparza. Both her paternal grandmother and her maternal grandfather were named Gonzales.

Esparza also identified a young girl, Trinidad Saucedo, as being with Doña Petra and described her as “…very beautiful,” in an interview in 1907. In an earlier 1902 interview he stated that she left the Alamo during an armistice in the siege. A census report of Bexar—Barrio del Norte, March 19, 1826, lists a Trinidad Saucedo as a 17-year-old servant in the household of Don Juan de Beramendi [Veramendi] and Josefa Navarro, the family who raised Juana Navarro Perez Alsbury. This Trinidad, 27 at the time of the battle, may have entered the Alamo with Alsbury and her sister.

Another census report of Bexar Barrio Sur, July 9, 1830, lists a 16-year-old Trinidad Saucedo in the household of Don Erasmo Seguin, making her 22 years old at the time of the battle. Erasmo’s son, Capt. Juan N. Seguin, served as an officer of the Alamo garrison until sent out by Travis for reinforcements, the highest-ranking officer to have left the Alamo during the siege. Trinidad of the Seguin household may have been the one remembered by Esparza.

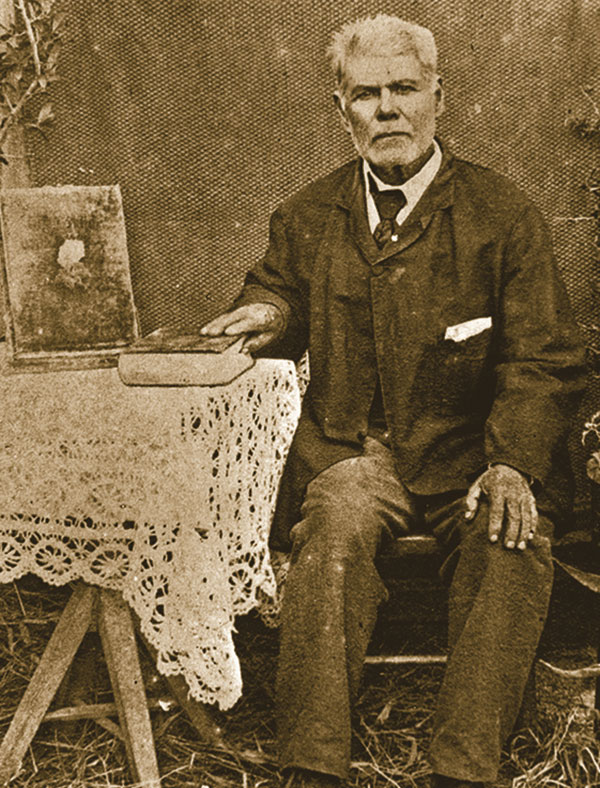

William Neale (1807-1896) a former mayor of Brownsville, Texas, told the story of Bettie to Texas Ranger and historian John S. Ford. He related that Bettie, a black slave, who claimed to have been Jim Bowie’s cook, arrived in Matamoras, Mexico, with the Mexican army after the battle of San Jacinto. Neale hired her and she remained with him for one to two years. According to Neale, Bettie survived the battle along with a male slave, Charlie, in the kitchen of the Alamo. After her time with Neale, fearful that she would be carried back to Texas in slavery, Bettie disappeared into Monterrey when Texan warships cruised near the mouth of the Rio Grande.

In his memoirs, John S. “Rip” Ford also related an account by Juana Alsbury in which she stated that after the battle, she and her sister Gertrudis were placed in the charge “…of a colored woman belonging to Col. Bowie and the party reached the house of Don Angel Navarro in safety.” Could this have been Bettie?

Finally, Joe, Travis’s slave, reported that one woman died in the Alamo battle. A correspondent for The Frankfort (Kentucky) Commonwealth stated in a May 25, 1836, letter, “Only one of the Negroes was killed—a woman—who was found lying dead between two guns. Joe supposes she ran out in her fright, and was killed by a chance shot.” Independent research by Ron Jackson and the late Thomas Ricks Lindley provide possible identification of this victim.

Ezekiel Hays petitioned Mexico six times in 1831-’32 for the return of a young mulatto slave named Sarah. According to his petitions she ran off to Texas with Patrick Henry Herndon. Herndon likely rode to the Alamo with the men under Jim Bowie. He died there, possibly with Sarah, the only couple to have lost their lives together at the Alamo.

The women survivors, along with their children, appeared before Santa Anna after the battle. He interviewed them, gave each two silver dollars and a blanket, and released them, these little-remembered participants of a well-remembered battle.

The women of the Alamo and their children

Bettie

Juana Navarro Perez Alsbury

Son: Alejo Perez Jr.

Susanna Dickinson

Daughter: Angelina Dickinson

Ana Salazar Esparza

Daughter: Maria de Jesús Castro

Son: Enrique Esparza

Son: Francisco Esparza

Son: Manuel Esparza

Possibly an infant daughter

Petra Gonzales

Concepción Charlí Gortari Losoya

Son: Juan Losoya

Juana Francisca Losoya Melton (daughter of Concepción Charlí Gortari Losoya)

Gertrudis Navarro

Sarah (possibly the only woman killed in the Alamo battle)

Victoriana de Salinas

Three small daughters

Trinidad Saucedo (may have left the Alamo during the siege)

William Groneman is a former New York City Firefighter, and a Western Writers of America sustaining member. He is author of Eyewitness to the Alamo.