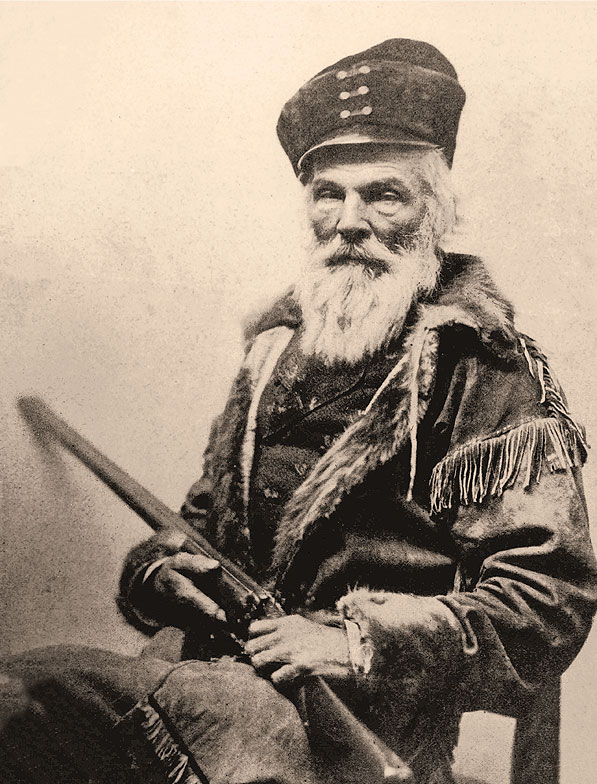

To describe Joseph Rutherford Walker as a typical frontiersman would be to label Abraham Lincoln a typical president. Walker was a man of many firsts: The first to guide a government survey party assigned to map the Santa Fe Trail; the first to find a navigable route over the Sierra Nevada Mountains to California; the first to lead an emigrant train over that route; the first white man to set eyes on the Yosemite Valley; and the first to discover the gold that initiated Arizona as a territory in 1863.

To describe Joseph Rutherford Walker as a typical frontiersman would be to label Abraham Lincoln a typical president. Walker was a man of many firsts: The first to guide a government survey party assigned to map the Santa Fe Trail; the first to find a navigable route over the Sierra Nevada Mountains to California; the first to lead an emigrant train over that route; the first white man to set eyes on the Yosemite Valley; and the first to discover the gold that initiated Arizona as a territory in 1863.

During his lifetime, Walker was more sought after as a guide than Jedediah Smith, Bill Williams, Joe Meek, Jim Bridger, Ewing Young or Kit Carson. People under the leadership of those guides often lost their lives. Anyone who traveled with Joe Walker survived, a claim no one else could make. Meek once admitted that “to accompany [Walker] on an expedition put a feather in a man’s cap.” The collective opinion of his fellow frontiersmen agreed: “…[Walker] didn’t follow trails, but rather made them.”

Walker was born in Roane County, Tennessee, on December 13, 1798. His father fought in the Revolutionary War and was a member of George Washington’s famous spy ring. Walker and his six siblings grew up among surveyors, war heroes and special government service agents.

In 1803, when Walker was four years old, President Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana Territory from France and sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their famous expedition. This glorious event fired the young Walker’s imagination and inspired his lifelong yearning to participate in America’s Westward Expansion.

At the age of 15, Walker, some members of his family and his kinsman Sam Houston joined the Tennessee Volunteer Mounted Gunmen, organized by Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. They participated in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, a decisive defeat for the Red Sticks, a force of Creek Indians initially organized by the great Shawnee leader Tecumseh.

By January 1815, Jackson and his army of roughly 4,700 soldiers, including his Tennessee militia, had defeated the British following the Battle of New Orleans. These victories added to Jackson’s reputation when he campaigned for President in 1825 and again in 1828, when he finally won by popular vote. Walker and other members of his clan forged a bond with the future president that lasted until Jackson died in 1845.

When Americans entered the highly lucrative fur trade, some of the best, untapped fur-trapping areas were located in the Spanish Southwest. The few trappers who ventured there were imprisoned or executed, and their furs confiscated. After Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821, William Becknell blazed the Santa Fe Trail, with five others, including Walker. Becknell expedited the sale of his trade goods at an astonishing profit. By early spring 1822, he was on his way back to Santa Fe, in what ultimately became New Mexico Territory, with three full wagonloads and 21 men, including Ewing Young and William Wolfskill.

Luckily for Becknell, Walker had stayed behind to trap beaver. Becknell spent weeks struggling to find a passable route for his wagons through the mountains, until he ran into Walker near the Arkansas River. With Walker’s help, he found a wagon route near the Cimarron River. For this discovery, Becknell has gone down in history as the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail,” an impossible success without his friend Walker. Years later, Walker’s modest comment about the event was, “I helped him [Becknell] break the crust.”

For the next few years, Walker and his Mountain Men friends became known as the Taos Trappers. They well understood how attention to the smallest details meant survival. Thirty years after having passed a place in his earlier travels, Walker still remembered where he could find water, game and forage.

In 1825, Walker set off to guide the first U.S. Government survey of the Santa Fe Trail. Upon the guide’s return to Fort Osage, Missouri, the governor asked Walker to select a site for a new town. Walker named the new town Independence and agreed to serve as Jackson County’s first sheriff. Walker’s calm but firm demeanor commanded such respect that not one murder was committed during his two terms in office.

One of his duties as sheriff was to watch out for runaway slaves and indentured servants. A 16-year-old apprentice by the name of Christopher Carson was just such a runaway. Walker took a liking to the lad. Rather than returning Carson to his master, who advertised a one-penny reward for him, Walker put him in the care of his Taos trapper friends. Wolfskill hired Carson to take care of his horses, nicknamed the boy Kit and eventually taught him to become a first-rate trapper. Walker, Wolfskill and Carson remained lifelong friends.

In 1830, Walker answered a summons from his cousin Sam Houston to come to Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. There, Houston introduced Walker to Capt. Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, who had been assigned by President Jackson to launch a fur trading expedition privately financed by John Jacob Astor. Historians believe that the true purpose of the mission, however, was to locate a navigable route over the Sierra Nevada Mountains to California and assess the strength of the Mexican armies stationed there. Bonneville wanted Walker to guide the venture.

In May 1832, a lavishly outfitted brigade of 110 men left Fort Osage, Missouri, equipped with 20 supply wagons and four horses per man. Walker recruited 40 trappers excited about the venture and anxious to explore the little known Pacific Coast.

For the next two years, Walker’s entourage endured incredible hardships, including Indian attacks, near starvation and treacherous descents through the freezing snow of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. In the process, they lost 24 horses, 17 of which provided food for the starving men. But despite their numerous near death experiences, not one of Walker’s men lost his life. When the Walker Party emerged from those treacherous mountains, they looked down upon the Yosemite Valley, the first white men to see it.

The Walker party took a different route home by working their way through the San Joaquin Valley. They found a low-lying pass through the mountains near the Kern River, later named Walker Pass. Walker would guide the first successful wagon train to California over this route in 1833. He would use the southern portion of Walker Pass 10 years later, while leading John C. Frémont’s expedition.

Walker reunited with Bonneville in time for the 1835 Mountain Man rendezvous near the Green River in modern-day Wyoming. Two years later, fashion turned to silk hats, and the fur trade died out.

From 1844 to 1846, Walker served as a guide for Frémont’s second and third expeditions to California. Frémont was the only man Walker ever disdained. “Morally and physically [he] was the most complete coward I ever knew..,” Walker noted.

After America’s defeat of the Mexicans in 1848, Walker settled down to ranching in the Monterey area of California and later in Contra Costa County, where most of his family had migrated by the 1850s. He remained in demand as a guide for both government and private expeditions. Walker was 62 years old in 1861, yet retained the energy and vitality of his youth. For 20 years, he had wanted to explore the southern region of New Mexico Territory (consisting today of Arizona and the southern tip of Nevada), but the region, considered Terra Incognita, was at the mercy of the fierce Apaches. When friends approached him about leading a prospecting party to look for gold there, Walker didn’t hesitate, despite the fact that he was going blind. Of the numerous discoveries and expeditions in which Walker participated, this adventure would stand out as his most memorable…and as his last.

By the spring of 1863, the Walker Party found the gold they had been looking for in north central Arizona. Their discovery would bring about the creation of Arizona Territory and the founding of the city of Prescott.

Walker spent his last years living with his nephew in Ygnacio Valley, California. He died October 27, 1876, at the age of 77, and he was buried in Alhambra Cemetery in Martinez. His name survives today on Walker Pass, Walker Lake, Walker River, Walker Valley, Walker Gulch, Walker Canyon, Walker Creek, Walker Trail, Walker Peak, Walker Mining District, Walker, Arizona, and Walker, California.

Kate Ruland-Thorne became fascinated with Joseph Rutherford Walker while researching her book, Gold, Greed & Glory, sharing the territorial history

of Arizona.